Obituary: Gough Whitlam

- Published

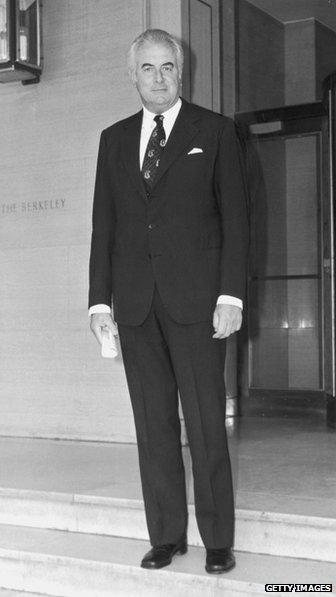

Gough Whitlam, the prime minister who changed Australia in the 1970s

Gough Whitlam found himself at the centre of a constitutional crisis after being dismissed as prime minister by Australia's governor-general in November 1975.

The most controversial prime minister in Australian history, Whitlam was a radical, reforming politician who sought to loosen the country's links with the United Kingdom.

He was a trenchant, charismatic force who instituted a number of far-reaching reforms while in office, including opening Australia up to non-white immigrants, reforming the honours system and establishing an equal opportunities policy for government jobs.

Gough Whitlam was born in July 1916, the son of a lawyer who also served as solicitor-general.

He was first elected to the Federal Parliament in 1952 and became deputy leader of the Labor Party in 1960. Seven years later he took over at the party's helm.

In the general election of December 1972 he became Australia's first Labor prime minister for 23 years but, within three years, in the election called after the governor-general's intervention, Whitlam's party was heavily defeated.

Senate woes

A barrister, he was a big man, 6'4" tall, strong, vigorous and handsome, and he enjoyed the power he had as prime minister. There were some who considered him the most able, most decisive and most dominating holder of the office since Robert Menzies.

Whitlam loosening links with the UK, but met the Queen in June 1976

In his early months of office, he shocked Australians out of their political apathy with many dramatic measures and delighted his supporters by his zeal.

He abolished conscription, ended Australian military participation in South Vietnam and released Vietnam draft resisters from prison. He recognised Communist China and warned the United States against renewed bombing in North Vietnam.

Whitlam also scrapped the Australian list of recommendations for New Year Honours and announced that Britons were in future to be classified as aliens.

It was under his leadership, too, that a new national anthem was chosen - though not to the total exclusion of God Save the Queen: he always denied that changes in the links with the monarchy were planned and did not hesitate to accept the Queen's invitation to visit her when he came to Britain.

But Whitlam's government was hampered by the lack of a majority in the upper house, the Senate, and he was also several times on a collision course with the six state parliaments that formed part of the Australian Federation.

In April 1974, Whitlam - goaded by Senate obstruction which had just culminated in its rejection of two money supply bills - called a general election and both houses were dissolved.

Crisis

His government was returned to power, with its majority in the House of Representatives reduced from nine to five and its position in the Senate improved but still a minority.

In the autumn of 1975, renewed trouble with the Senate over the Federal budget caused an even more serious constitutional crisis.

Opposition Leader Malcolm Fraser offered to back down if he got a pledge of a general election by the middle of 1976 but Whitlam, encouraged by increasing evidence of popular support, insisted that he would not call an election for at least 12 months.

On 11 November, Governor-General Sir John Kerr stepped in and dismissed Whitlam, saying he did so because of the prime minister's failure to get parliament to approve the budget and his subsequent refusal to resign or call an election.

Whitlam was removed by the governor-general amid an impasse over the budget

Malcolm Fraser was appointed to head a Liberal-Country Party coalition government until an election in December.

Kerr's unprecedented action shocked the country and, with Gough Whitlam exhorting his supporters to "maintain your rage", sparked off protest strikes and violent demonstrations. With indignation at boiling point the electorate at first cooled towards Fraser.

But as the campaign developed, the focus shifted from the constitutional issue to Labor's performance in office and, terminally damaged by unemployment, inflation and scandal, Whitlam's party suffered a crushing defeat at the polls, leaving Fraser's coalition with a clear majority in both houses.

In the months that followed, Gough Whitlam tried hard to keep alive what he saw as the injustice of his dismissal. He campaigned vigorously against it, and accused the governor-general and the new prime minister of being deceitful men.

Early in 1976, he was re-elected leader of the parliamentary Labor Party, but in March he and two other officials were sharply criticised by a party inquiry for what were seen as grave errors of judgment in an alleged attempt to get election campaign funds from Iraq.

During the spring and summer of 1977, Whitlam's future as head of his party remained in the balance and, in another contest for the leadership in June, he just held on, by 32 votes to 30.

When Labor lost the election that December Whitlam did not seek re-election as party leader and, the following July, he announced his retirement from politics to become a visiting fellow of the Australian National University in Canberra. Later he became Australia's ambassador to Unesco.

Gough Whitlam remained a familiar figure on the Australian social scene right into his 90s. His view of himself was typically direct: "I don't say I was a good prime minister but I do accept the general view that I was the best."