Australia asylum: Detention 'harms children and violates law'

- Published

The report says that many young people are traumatised by their experiences in detention

Australia's policy of detaining the children of asylum seekers causes them harm and violates international human rights law, a report says.

A third of detained children had developed mental illnesses of such severity that they required psychiatric treatment, the Australian Human Rights Commission, external (HRC) said.

It called for all detained children to be released immediately.

PM Tony Abbott has called the report a blatant attack on his government.

Mr Abbott said the commission "should be ashamed of itself" for being so partisan.

Under his government the number of children in detention has fallen. Mr Abbott questioned why the HRC did not launch an inquiry when the Labor government was in power and there were almost 2,000 children in detention centres.

Successive Australian governments have been criticised over their harsh asylum policies, under which asylum seekers are detained for long periods in offshore camps while their applications are processed.

Opinion polls show that such policies are popular with voters concerned about asylum seekers arriving in Australia by boat.

The Human Rights Commission report features drawings by children which depict the misery of the camps

'Cruel and illegal'

The long-awaited report, entitled The Forgotten Children, was completed late last year and released by the government on Wednesday.

It argues that there is no sensible explanation for the prolonged detention of children which is "in clear violation of international human rights law".

"The overarching finding of the enquiry is that the prolonged, mandatory detention of asylum-seeker children causes them significant mental and physical illness and developmental delays, in breach of Australia's international obligations," the foreword says.

The report found that:

Detained children have significantly higher rates of mental health disorders than children in the community.

Children held offshore on the Pacific island of Nauru are suffering from "extreme levels of physical, emotional, psychological and developmental distress".

Multiple reports of assaults, sexual assaults and self-harm involving children "indicate the danger of the detention environment".

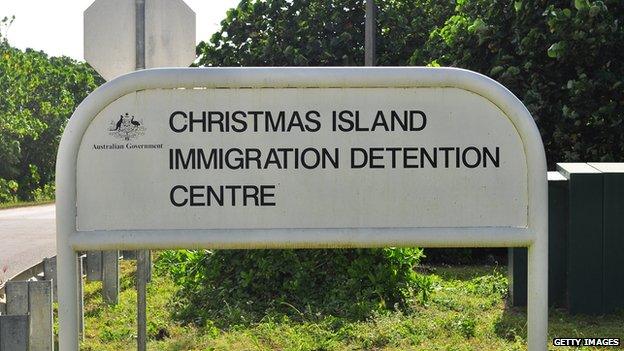

It calls for the closure of immigration detention facilities on Christmas Island, an end to indefinite detentions and the replacement of the immigration minister by an independent person to act as guardian for unaccompanied children.

"The aims of stopping people smugglers and deaths at sea do not justify the cruel and illegal means adopted," Commission President Gillian Triggs wrote.

"Australia is better than this."

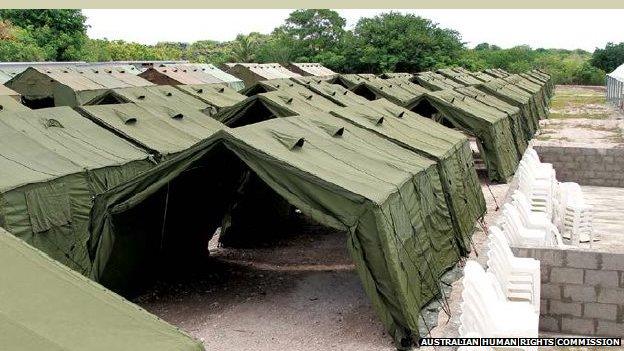

Refugees are kept in detention centres waiting for their claims to be assessed

The island of Nauru is home to hundreds of asylum seekers awaiting decisions on their refugee claims

Immigration Minister Peter Dutton said many of the recommendations in the report were unnecessary, while others "would mean undermining the very policies that mean children don't get on boats in the first place".

Attorney General George Brandis said that the government did not accept the commission's conclusions.

Australia currently detains all asylum seekers who arrive by boat, holding them in offshore processing camps. Those found to be refugees will not be permanently resettled in Australia.

It also has a backlog of cases - about 30,000 - relating to asylum seekers who arrived before the current policies were put in place. Those people live in detention camps or in the community under bridging visas that do not allow them to work.

The opposition Labor party, the Greens and human rights groups have called for significant changes to the immigration detention network following publication of the report.

Australia and asylum

Asylum seekers - mainly from Afghanistan, Sri Lanka, Iraq and Iran - travel to Australia's Christmas Island by boat from Indonesia

The number of boats rose sharply in 2012 and early 2013. Scores of people have died making the journey

To stop the influx, the government has adopted hard-line measures intended as a deterrent

Everyone who arrives is detained. Under a new policy, they are processed in Nauru and Papua New Guinea. Those found to be refugees will be resettled in PNG, Nauru or Cambodia

Tony Abbot's government has also adopted a policy of tow-backs, or turning boats around

Rights groups and the UN have voiced serious concerns about the policies and conditions in the detention camps. They accuse Australia of shirking international obligations.