Does Australia's farm sector need foreign investment?

- Published

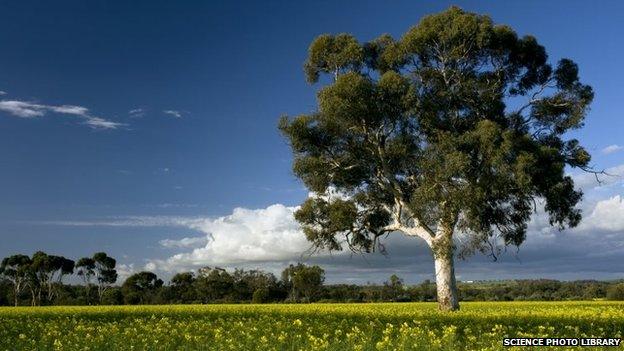

Foreign land ownership is controversial in Australia

Foreign investment in Australia is rarely far from the headlines with claims offshore buyers are inflating house prices and controlling too much of the country's food production. But when it comes to the farm sector, there is another side to the story.

Australians are adept at tut-tutting about how much of the country's agricultural land has been sold to foreigners.

Fuelled by regular reports about China's growth, its appetite for Australian sugar, beef, sorghum and more, and its purchase in 2013 of Australia's biggest cotton producer and irrigator on the border of Queensland and New South Wales, it is perhaps not surprising.

According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, foreign investors own 10% of Australia's agricultural land, a figure little changed in 25 years.

But that could soon rise thanks to two huge projects being developed in Northern Territory's Top End with the help of foreign investors.

Chinese conglomerate Shanghai Zhongfu is developing 15,200 hectares (37,560 acres) of valuable agricultural land in Western Australia in what is known as the Ord Stage 2 project. It will grow sugar and sorghum.

Australian company Integrated Food and Energy Developments (IFED) in North Queensland is looking for capital for a A$2bn ($1.6bn, £1.02bn) beef, guar bean and sugar venture.

Public pressure

This kind of development is crucial if Australia wants to realise what many believe is its potential to double agricultural production by 2030, says National Farmers' Federation (NFF) chief executive officer Simon Talbot.

"Australians aren't falling over themselves to invest in agriculture," Mr Talbot explains.

The government has said that it is tightening the rules for foreign investment in agricultural land

"When it comes to opening up northern Australia, we can't do that without foreign investment."

But under public pressure to keep farms in Australian hands, as of 1 March the government is requiring cumulative sales of farmland to foreign investors worth more than A$15m to be approved by the Foreign Investment Review Board (FIRB).

Previously, approval was only required for deals worth more than A$252m.

From 1 July, the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) will start collecting information on all new foreign investment in agricultural land, regardless of value - to take stock of what is owned by foreign investors.

Uncertainty

The FIRB threshold and the register should help give Australians the peace of mind they have been looking for without stemming the flow of foreign capital, says Mr Talbot.

"There is massive demand for protein - dairy and beef - and horticulture, as well as grains and fibre, and China in particular is interested in areas like Tasmania and southern Western Australia. I don't think this is going to deter foreign investment," he says.

He would like to see some assurances from investors about how they will engage with communities and industries they are investing in, and he says the NFF will be discussing that with the government.

"We have learnt the hard way from early mining developments that agreements need to be in place post-investment," he says.

Goondiwindi-based cotton and grain grower Peter Corish is another who says Australia needs to be careful not to put unnecessary impediments in the way of foreign investors.

Mr Corish says a register would be a more important development than lowering the FIRB threshold

"There's a lot of uncertainty about foreign investment in agriculture," says the Queenslander. "A register will give us transparency. That's a more important step than lowering the FIRB threshold."

Mr Corish is formerly chairman and managing director of Australian agricultural conglomerate PrimeAg, which sold most of its cotton and cropping properties to two US fund managers, Teachers Insurance and Annuity Association (TIAA-CREF) and Global Endowment Management, in 2013.

He says domestic fund managers considered buying PrimeAg's assets but did not follow through. So, without a sale to the US funds, returns to shareholders would have been lower.

"Australian superannuation [pension] funds are chasing much higher returns than overseas ones. It's as simple as that," he says.

Quick expansion

Control of food production does not have to come through land ownership.

Paul O'Meehan farms 4,800 hectares of his own land in southern Western Australia and leases another 8,000 hectares from TIAA-CREF, making him one of the region's biggest producers of wheat, barley, canola, lupins and peas.

"They own the land and we rent it from them at a percentage of the value. All the grain is ours, and they put in things like buildings, roads, silos," explains Mr O'Meehan.

"If I tried to expand like this myself, I could buy 1,000 to 2,000 acres every few years. I've done what I wanted to do in two years instead of two generations," he says.

- Published25 February 2015

- Published29 October 2014

- Published11 February 2015

- Published31 October 2013