The secrecy surrounding Australia's asylum camps

- Published

Very few images have emerged showing conditions on Manus Island

Australia's policy of detaining asylum seekers in offshore facilities, for months, even years, has attracted strong criticism from bodies such as the United Nations. But government secrecy surrounding the operation of these isolated centres means many Australians know little about what life is like for those detained inside.

When journalist Eoin Blackwell needs to find out what's going on inside Australia's immigration detention centre on Papua New Guinea's (PNG) Manus Island, he calls his local contacts.

Mr Blackwell doesn't bother making official inquiries because, in his experience, information or access requests made to the Australian and PNG governments are ignored or forgotten.

"Every request I've made with the government to do with Manus has been denied or delayed until it went away," says Mr Blackwell, a former PNG correspondent for Australian Associated Press.

"One time I tried to get into the centre and the Australian government said it was up to the PNG government and the PNG government said they had to call Canberra. Eventually we were told 'no' but no one would say who was telling us no," says the reporter, expressing the frustration many journalists feel about the secrecy surrounding the centre.

The BBC sent a number of written questions to the Australian Immigration Department for this story but at the time of writing had not received a reply.

No-man's land

Located in the Bismarck Sea and more than 800km (500 miles) north of the PNG capital Port Moresby - or a 3,500 km, 10-hour flight from Sydney - Manus is one of PNG's most remote islands.

Few among the 65,000 population have benefitted from the billions of dollars successive Australian governments have spent converting a navy base into a no-man's land for asylum seekers trying to reach Australia.

Journalists outside PNG can't enter Manus Island without a visa and approval from PNG's Department of Foreign Affairs and Immigration, but permission is rarely given. Following Mr Blackwell's departure in 2013, there was only one Australian media correspondent left in PNG, the ABC's Liam Fox.

The Australian government, under former Prime Minister John Howard, set up the detention centre on Manus Island in 2001 as part of its so-called Pacific Solution to detain asylum seekers offshore while their refugee status was determined.

Manus was closed in 2008 by Labor Prime Minister Kevin Rudd but was reopened by his successor Julia Gillard in late 2011.

The difficulty of finding out what is going on in the centre was highlighted in early 2014 when riots broke out inside its gates. More than 60 asylum seekers were injured and 23 year-old Iranian asylum seeker Reza Berati was killed.

Conflicting reports soon emerged from government and refugee sources about exactly what took place.

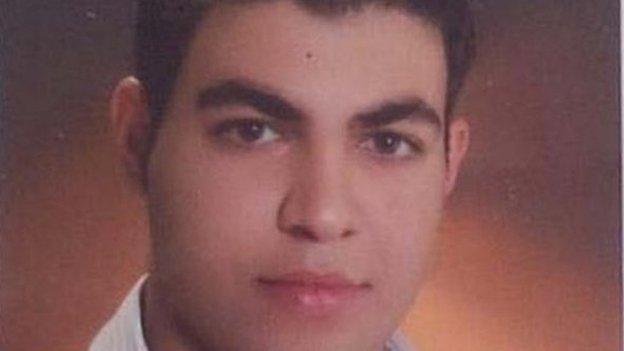

Reza Berati's death in February 2014 at Manus Island prompted protests from activists

It wasn't until May last year that an independent report by Australian former senior public servant Robert Cornall found Mr Berati had died after he was clubbed over the head by a locally-engaged Salvation Army employee.

A year later, conflicting stories emerged about a fresh round of hunger strikes and self-harm at the centre. Australian Immigration Minister Peter Dutton blamed refugee advocates for encouraging asylum seekers to protest.

'Pit of human misery'

Despite the wall of secrecy, Mr Blackwell, who is now based in Sydney with AAP, has visited Manus Island five times.

He paints a grim picture of what life is like for more than 1,000 male asylum seekers in a centre now infamous for two detainee deaths (in September another Iranian refugee died from septicaemia after cutting his foot), describing hot, harsh conditions, malaria, overcrowding, poor hygiene, riots, hunger strikes, mental illness and water shortages.

The reporter gained entry to the centre in March last year when he accompanied a PNG Supreme Court judge who was doing an inspection as part of a human rights case.

"Foxtrot (one of four Manus compounds) was a pit of human misery," Mr Blackwell recalls.

"The refugees live in shipping containers, there's water everywhere, lights not working, the heat is oppressive, no windows. There was a (detainee) with a bandage over his eye... asking for help in this stinking, hot compound."

Conditions in the camps have been criticised by NGOs and the UN

Refugee Action Coalition's Ian Rintoul says he relies on first-hand, eyewitness reports from people inside the centre, as well as video and images supplied by detainees and staff via mobile phones.

But he says after this year's hunger strike, an estimated 40 to 50 mobile phones were seized in a security crackdown.

"Since the hunger strike, [authorities] have mounted CCTV cameras all through the centre," says Mr Rintoul.

"In some compounds, guards wear cameras on their uniforms. There are routine patrols in the yard and the rooms. Staff are checked with security wands on the way in and out."

Mr Rintoul claims the Australian government doesn't want the public to know what is really going on inside the centre.

"That is why journalists and mobile phones are excluded. But when the footage comes out they can't maintain the pretence," he says.

Australia and asylum

Asylum seekers - mainly from Afghanistan, Sri Lanka, Iraq and Iran - have been travelling to Australia's Christmas Island on rickety boats from Indonesia

The number of boats rose sharply in 2012 and the beginning of 2013, and scores of people died making the journey

Everyone who arrives is detained. They are processed in camps in Christmas Island, Nauru and Papua New Guinea. Those found to be refugees will be resettled in PNG or Cambodia, not Australia

Rights groups and the UN have voiced serious concerns about the policies, and about conditions in the offshore camps

- Published9 March 2015

- Published15 January 2015

- Published3 September 2014

- Published31 October 2017