Anzac Day: Commemorate or celebrate?

- Published

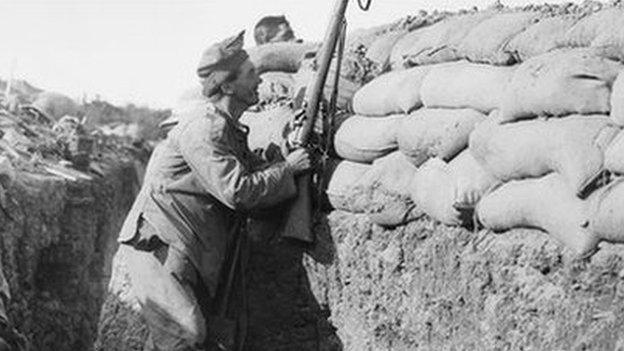

In New Zealand, Anzac Day tends to be commemorated in a reflective fashion

Anzac Day, 25 April, is probably Australia's most important national occasion. It marks the anniversary of the first campaign that led to major casualties for Australian and New Zealand forces during World War One and commemorates all the conflicts that followed.

This year marks the centenary of that first bloody battle on the shores of Gallipoli. It will be remembered across the country and in Turkey with special ceremonies and exhibitions. In this second feature in our series on Gallipoli, Megan Lane for BBC News looks at how New Zealand commemorates its role in the battle.

It can be revealing to ask children born 90 years after the World War One campaign fought by the Australia and New Zealand Army Corps (Anzac) what they think the initials stand for.

"Appreciation New Zealand Australia Co-operation," suggested one pupil in a straw poll of 10-year-old primary school students in New Zealand's Wellington and Australia's Melbourne - a pleasingly wrong answer that said much about Anzac Day in the 21st Century.

Co-operation was a popular choice for the New Zealand 10-year-olds, while the Australians were more likely to opt for "crew" - a modern, matey version of "corps".

Co-operation and crew. Wrong but also right.

Around 8,500 Australians and nearly 3,000 New Zealanders died at Gallipoli, as well as 87,000 Turks

On 25 April 1915, soldiers from Australia and New Zealand landed at Gallipoli Cove, part of an Allied effort to capture the peninsula from the Ottoman Empire.

Collectively termed Anzacs by a military clerk keen to fit the name on a rubber stamp, the acronym stuck.

After an eight-month campaign, the Allies retreated in defeat after heavy losses on both sides. More than 87,000 Turks died, along with an estimated 44,000 men from the British Empire and France, including 8,500 Australians and nearly 3,000 New Zealanders - one in four of the Kiwis sent to Gallipoli.

The first Anzac commemorations were held in 1916. A century later, these have morphed into big-budget productions in Australia, New Zealand and Turkey.

While part of the international trend for war commemoration, Anzac Day has become more of a national day than Australia Day, says Prof Mark McKenna of the University of Sydney.

By contrast, New Zealand regards Anzac Day as one of - not the - defining experience.

Its national day marks the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi between Maori chiefs and the British Crown.

"Australia went through a long debate in the 1980s and 1990s about its legacy of colonialism and dispossession [of local indigenous people]," says Prof McKenna. "Anzac Day was a less complicated alternative as it involved the 'honourable deaths' of Australians."

Glyn Harper, professor of war studies at New Zealand's Massey University, agrees. "I don't think New Zealand's myths around Gallipoli are as strong as in Australia, where the term 'Anzac' has become almost sacred."

He points to the contrasting moods on Anzac Day. "In New Zealand, the emphasis is on the dawn service. It's a time of reflection on the cost of war and how it shaped the country."

"In Australia, the dawn service is important but the focus is on the 11am military parade. People clap and cheer as the military units go past. It starts with reflection but later it becomes something to celebrate."

Australia tends to focus on its morning military parade to mark Anzac Day

Why is there so much emphasis on this campaign? As interest in family history and war tourism has grown, so too has Anzac Day's popularity, says Charles Ferrall, an Australian expatriate at Victoria University of Wellington and co-editor of the book How We Remember: New Zealanders and the First World War.

The sense of 'mateship' in the face of adversity has been the lasting legacy of the Anzac troops

It was the Anzacs' first major engagement on the world stage, fought by the grandfathers and great-grandfathers of today's New Zealanders and Australians.

Then there was Gallipoli, the 1981 hit film that made a star of a young Mel Gibson. Its lyrical account of plucky Aussie soldiers sent over the top by blundering officers reflected - and fed - the rise of nationalism and of mateship as a defining national characteristic in both countries.

"There was a sense that Britain didn't matter anymore. America mattered, so you could afford to crank anti-British sentiment up," says Mr Ferrall.

"So the old story was told again about how our boys were killed by foolish English generals. It had enough truth in it to hold but what happened was more nuanced than that."

With the death of the last Anzac veterans a decade ago, a number of historians and cultural commentators have expressed fears the true events of Gallipoli have been forgotten. "Australians can see and hear the 'A' but where's the 'nzac'?" asks Mr McKenna.

But for Mr Harper, the strength of feeling around Gallipoli is positive.

"Very few nations commemorate a loss. This wasn't a great victory, it was a battle marked with incompetence, muddle and catastrophe. The best part of that campaign, the best planned and most effective, was when we left," he argues.

"What resonates with people was how these soldiers behaved under adverse conditions: perseverance, friendship, courage in the face of adversity. The soldiers gave it everything but it wasn't enough. By doing so, they established something people want to hold on to."

So does that make Anzac Day a sad occasion?

Sad and happy, says a number of the 10-year-olds questioned for this story: "Sad, because of those who died. And happy - they risked their lives for our country."

- Published23 March 2015

- Published19 February 2015

- Published9 April 2015