Could Australia's tough approach to migrants work in Europe?

- Published

People in Malaga hold a banner reading "No more deaths in the Mediterranean" during a protest against the EU's current immigration policy

Once associated with carefree summer holidays, the Mediterranean is becoming better known as a graveyard. As thousands of migrants drown, the European Union seems paralysed by its most intractable policy dilemma for decades.

Advocates of the Australian government's tough approach to unauthorised migrants believe that eventually Europe will end up with a similar policy.

"You have, in the Mediterranean, three choices," former Australian Foreign Minister Alexander Downer told Newshour Extra.

One option is to maintain the status quo. But, he argues, that would mean more people will drown.

The Liberal Party's Alexander Downer was Australia's foreign minister in 1996-2007

Alternatively Europe could decide that Africa and the Middle East are so dangerous and impoverished that the migrants should be allowed to move. In that case, Mr Downer argues, "Europe should provide proper shipping to bring people to Europe."

If, however, Europe wants to stop the drownings in the Mediterranean but does not want open borders, Mr Downer says, then it will have to turn boats back.

When he was foreign minister from 1996 until 2007, Mr Downer was fiercely criticised for preventing people reaching Australia by boat. Similar policies are now being implemented with even greater vigour by the government of Prime Minister Tony Abbott.

The policy has had a significant impact. In 2013 some 300 boats with more than 20,000 unauthorised migrants got to Australia. In 2014 just one vessel reached the country.

Important differences

Critics say that all the data related to the migrants' maritime movements is suspect because the Australian authorities are secretive about their actions at sea. They also argue that Australia is merely moving the problem elsewhere. Persecuted and and impoverished Afghan migrants, for example, used to try to get to Australia. With that route blocked, Afghans are now amongst those trying to reach Europe.

While European policy makers are well aware of the Australian model, they also know that there are significant differences between the Australian and European situations.

First, the numbers in Europe are far greater. Last year 170,000 people tried to cross the Mediterranean. EU officials believe that number could increase rapidly. Fabrice Leggeri the executive director of Frontex, the EU agency responsible for protecting Europe's external borders, told the Italian news agency Ansa, external that "anywhere between 500,000 to a million people" are ready to leave from Libya.

The largest migrant group coming to Europe, by nationality, in 2015 is from Syria

It's not just a question of scale. Whereas countries such as Indonesia have the capacity to cope with returned boat people, Libya with its chaotic civil conflict, does not.

According to Frontex, the three countries that produced the largest numbers of migrants in 2013 were Afghanistan, Syria and Eritrea. Leaving migrants from these countries penniless on the beaches of Libya's failing state, would raise huge moral and political questions as well as possibly insuperable legal ones.

Australia's 'stop the boats' policy:

The previous Labor government reintroduced offshore processing in Nauru and Papua New Guinea in September 2012 - a policy it had ended in 2008 - whereby it pays outsourced contractors to operate and provide security at temporary detention camps for asylum seekers on the Pacific islands

It also reached a deal with Papua New Guinea that any asylum seekers judged to be genuine refugees would be resettled in Papua New Guinea, not Australia

The current Liberal-National coalition government adopted Labor's policies and expanded them, introducing Operation Sovereign Borders, external, which put the military in control of asylum operations

Under this policy military vessels patrol Australian waters and intercept migrant boats, towing them back to Indonesia or sending asylum seekers back in inflatable dinghies or lifeboats

In 2013 some 300 boats carrying illegal migrants reached Australia. In 2014 the number was just one

Processing centres

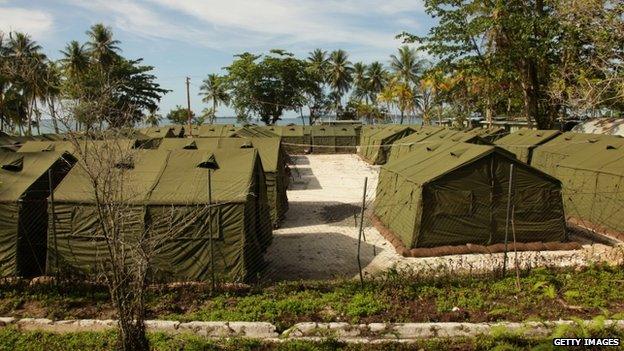

The Manus Island Regional Processing Facility in Papua New Guinea is used for the detention of asylum seekers who arrive by boat to Christmas Island or the Australian mainland

Australia allows some 200,000 people a year to settle in the country legally. But it now says that no-one arriving on an unauthorised boat, even if he or she is a genuine refugee, will be allowed to settle on Australian soil.

Instead they are moved to processing centres on remote Pacific Islands in Nauru and Papua New Guinea. The Australian government's plan is then to screen the migrants and move genuine refugees to third countries such as Cambodia.

UN officials have described the policy as a departure from international norms that could result in the world's poorest countries being the only ones to accept the burden of genuine refugees.

Critics have also pointed to significant problems at the Pacific Island processing centres. There have been cases of riots, hunger strikes, brutality by guards and the sexual abuse of children. Journalistic reports from the processing centres depict great frustration and despair as asylum seekers and would-be migrants wait to find out what will happen to them. Some people at the camps have resorted to stitching their lips together.

But Mr Downer believes the Australian model could work in Europe. "You could build processing centres in North Africa," he says. He suggests that if people in the processing centres are found to be genuine refugees then they could be resettled in Europe. "If not, you need to send them back to whence they came."

For more on this story, listen to Newshour Extra on the BBC iPlayer or download the podcast.