Australian churches offer to take in asylum seekers

- Published

Uniting Church minister Margaret Mayman spoke at a protest outside the immigration department in Sydney on Thursday

Australian churches have said they will offer sanctuary to asylum seekers who face deportation to Nauru.

The High Court on Wednesday found Australia's policy of sending asylum seekers to government-funded offshore processing centres was constitutional.

The decision means people, including 37 babies, face deportation to the detention centre on Nauru.

The Anglican Dean of Brisbane Dr Peter Catt said they would likely face trauma and abuse if deported.

"This fundamentally goes against our faith so our church community is compelled to act, despite the possibility of individual penalty against us," Dr Catt said in a statement.

"Historically churches have afforded sanctuary to those seeking refuge from brutal and oppressive forces."

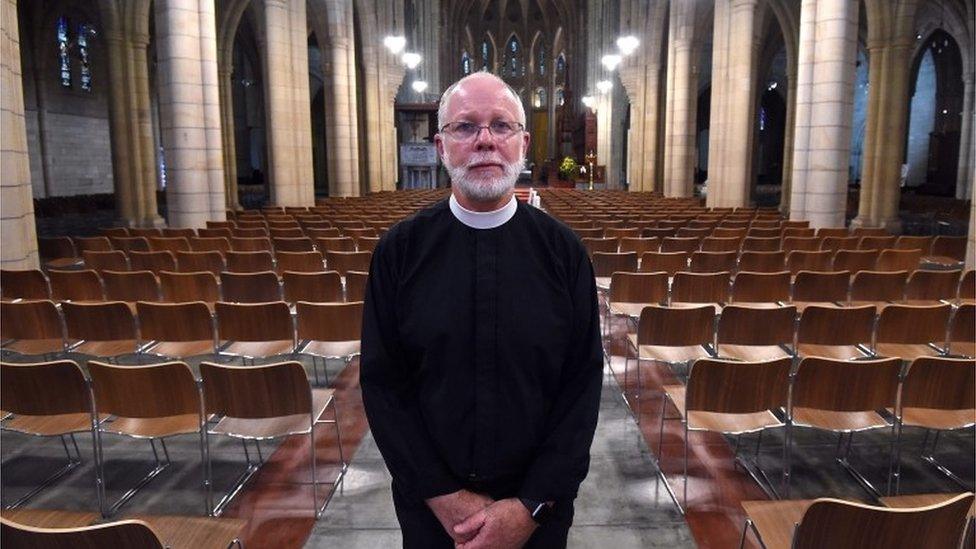

Dr David Catt said Brisbane Cathedral would be open to take in asylum seekers

Ten Anglican and Uniting churches are offering sanctuary, including Brisbane Cathedral.

Ian Rintoul of the Refugee Action Coalition welcomed the move, but said it would be largely symbolic as only about 30 of the asylum seekers were in the community and able to attend a church. The rest are in detention centres.

Individual cases

The churches' offer comes as pressure builds on Immigration Minister Peter Dutton to allow the group to remain in Australia.

Mr Dutton told the Australian Broadcasting Corp, external that no child would be "put in harm's way".

"We are going to work individually through each of the cases," he said.

The island nation of Nauru holds migrants while Australia processes their asylum claims

Australia intercepts all boats bringing suspected asylum seekers to its territory and takes those on board to Nauru or to Manus Island in Papua New Guinea.

Even if they are found to be genuine refugees they will not be allowed to settle in Australia.

The government says the policy deters people smuggling and saves lives at sea, but it has been widely criticised as breaking Australia's legal obligations.

Jon Donnison, BBC News, Sydney

The announcement that the Anglican Church is to offer sanctuary to the asylum seekers affected by this week's High Court ruling has attracted widespread media coverage.

But it is a largely symbolic gesture.

The vast majority of the 268 people now faced with being forced to return to Nauru have been locked up in mainland Australian detention centres pending the High Court decision.

In other words, even if they wanted to take sanctuary in a church, they are not free to do so.

Only a handful are living amongst the community.

Many would think the government would be concerned about the negative coverage the story has generated internationally, with Australia being portrayed by many as cruel and lacking in compassion.

But ministers also know that domestically, their tough policies towards asylum seekers have broad public support.

The headline in one of Australia's best selling newspapers, Sydney Daily Telegraph, this morning was "Turn Back the Kids."

Trauma report

Most of the children expected to be deported after the High Court ruling are being held with their families at the Wickham Point detention facility.

A medical report commissioned by the Australian Human Rights Commission has found the 95% of children held there showed risks of post-traumatic stress disorder.

The doctors who wrote the report said the children were among the most traumatised they had ever seen.

"We were deeply disturbed by the numbers of young children who expressed intent to self-harm and talked openly about suicide and by those who had already self-harmed," Dr Hasantha Gunasekera said.

Prof Gillian Triggs, president of the Australian Human Rights Commission, called on Australia to uphold its international treaty obligations to protect vulnerable people.

"These responsibilities remain whether or not third-country processing is authorised by Australian law," Prof Triggs said.

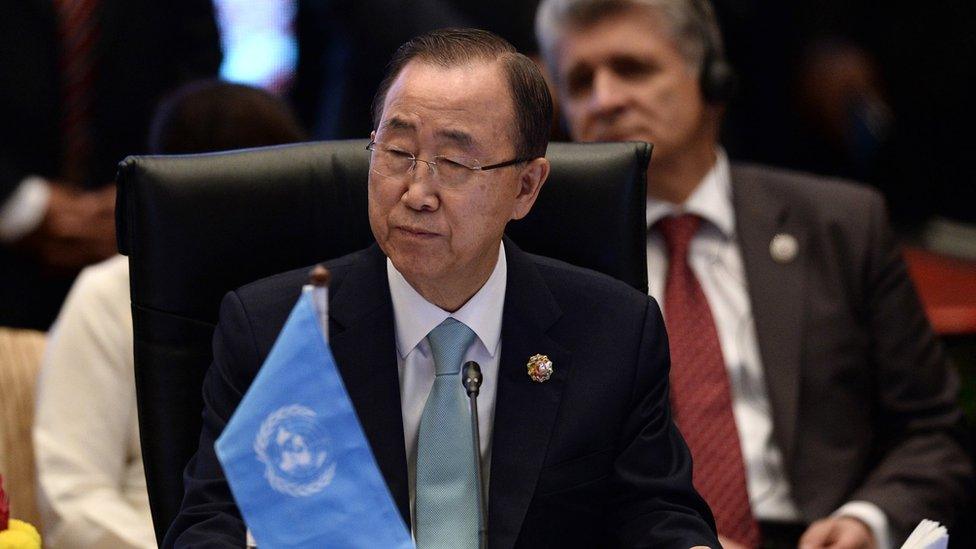

The UN also expressed concern , externalabout the ruling, and urged the Mr Dutton to "refrain from transferring all concerned individuals to Nauru".

But Mr Dutton defended the government's border protection measures, saying the number of children in detention had decreased from a peak of 2,500 under the previous Labor government to around 80.

"There were 1,200 people who drowned at sea, including women and children, the voices of whom have never been heard," he told the Australian Broadcasting Corp., external

"Many of the advocates you speak of are completely opposed to any border protection measures at all."

- Published3 February 2016

- Published23 November 2015

- Published31 October 2017