Are health experts turning Australia into a nanny state?

- Published

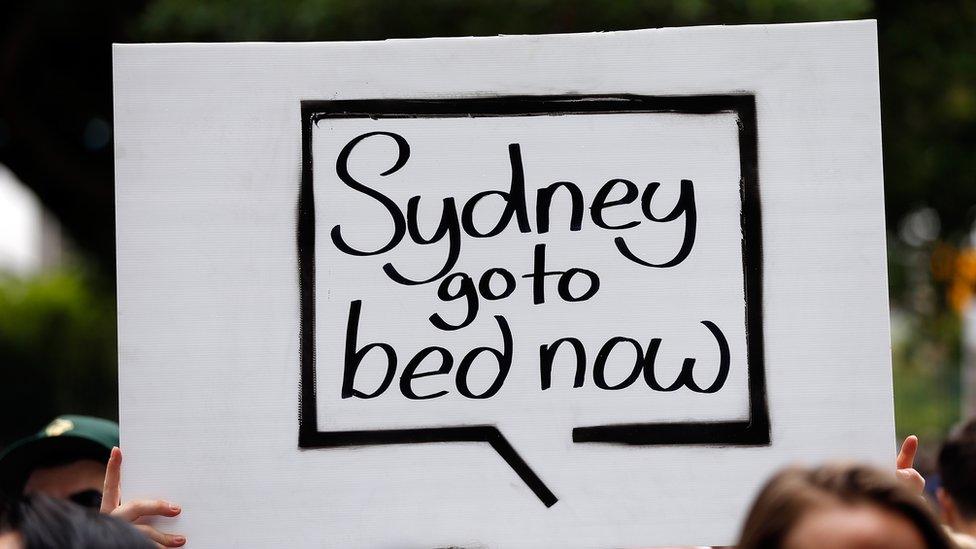

'Lockout laws' restricting the sale of alcohol in Sydney's entertainment precincts have stoked public anger against 'nanny state' laws

In the Australian state of New South Wales, tiny inflatable pools deeper than 30cm must have a fence around them. This fence must be at least 1.2 meters tall and have a self-latching gate.

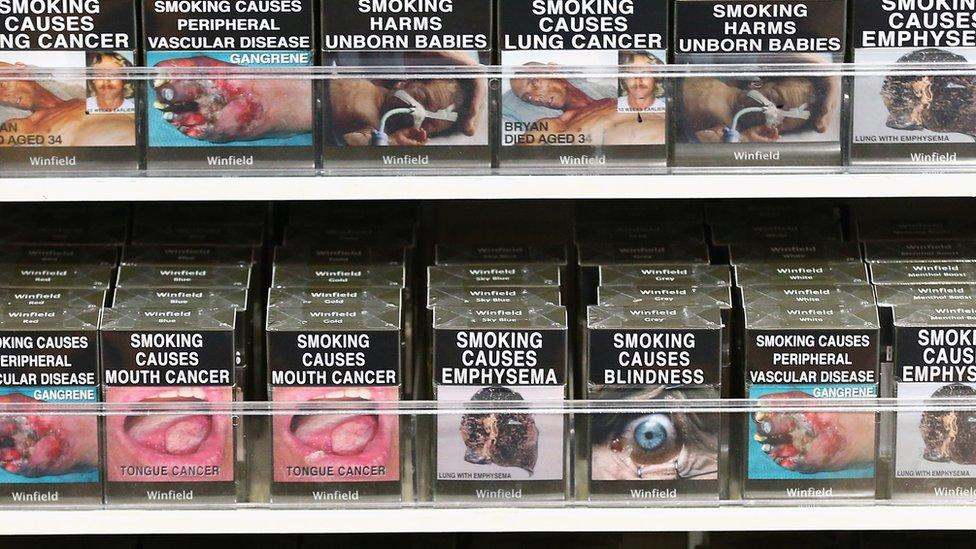

Bike riders risk a A$319 ($239, £168) fine for not wearing a helmet and a $425 fine for riding through a red light. Plain packaging is mandatory on boxes of cigarettes, not just in New South Wales but across the country.

Most controversial of all are "lockout laws" which, since February 2014, have required bars in Sydney's main entertainment precincts to shut their doors to new patrons from 01:30 and stop serving drinks from 03:00. You can't buy a bottle of wine from a store after 22:00.

Many residents feel as though they're drowning in a sea of cotton-wool legislation.

"We have a group of people who are fairly contemptuous of their fellow Australians," says Liberal Democratic Party Senator David Leyonhjelm, of the bureaucrats and politicians responsible for the laws in question.

Senator Leyonhjelm, a self-described libertarian, is behind a Senate inquiry into the necessity of laws on bicycle helmets, marijuana and film classifications. Even the issue of mandatory pool fences may get an airing at the inquiry's final hearing.

"We have a history of respect for authority... The notion that we were ever a 'larrikin' (loutish) country is largely mythological."

Bike riders in the state of New South Wales are now fined A$319 if they are not wearing a helmet

The senator doesn't deny that all developed countries, to varying degrees, are rife with nanny state rules. The argument that Australia is a nanny state would probably not make sense to women in Saudi Arabia, or even in parts of the USA who have been prevented from having an abortion.

But Senator Leyonhjelm and other critics say the outsize influence of public health advocates in Australia has created a unique form of the nanny state not seen in comparable Western democracies.

Leyonhjelm compares Australia to the United Kingdom. As the influence of organised religion waned there, public health advocates, who often share the same obsession with purity and healthy living, were not able to fill the void in the way they have in Australia, where health experts have lobbied for measures that amount to "proxies for disapproval."

Apart from the Alcohol Act in Scotland, which restricts bargain offers from supermarkets, the United Kingdom has comparably few rules that prevent when and where people can buy alcohol. Australia, by contrast, has mandatory bicycle helmets, bans on fireworks, bans on e-cigarette liquid containing nicotine and a large suite of restrictions on the sale and service of alcohol, Leyonhjelm says.

'A lazy line'

It's true that medical professionals and police are big fans of the lockout laws in particular, which have now also been introduced in the state of Queensland.

Stephen Parnis is an emergency room doctor who regularly treats victims of drunken violence. He's also the vice-president of the Australian Medical Association.

"I think the term 'nanny state' is a very lazy throw-away line," Dr Parnis says.

"It's a very fashionable term to use, from people who don't like some of the measures that are out there.

"Alcohol causes more harm than all the other drugs altogether."

Australia introduced laws in 2012 that made plain packaging compulsory for tobacco products

The lockout laws strike the right balance and are keeping people safe, he says, explaining that while everyone should have a say in the law, whose opinion carries the most weight or authority is another question.

"Someone's [uneducated] opinion is not necessarily evidence," he says.

Paul Griffiths, a professor of philosophy at the University of Sydney, says Australia is currently facing a push from libertarian politicians to water down health legislation, but warns that reducing the power of democratic governments means less freedom, not more.

"It's not whether or not there are a whole bunch of laws that determine if you are free or not," he says.

A better measure, Prof. Griffiths says, is whether or not most people affected by laws that restrict personal choices feel as though their views were listened to.

"You should make your government more democratic, not argue for fewer laws."