Machine that 'unboils' eggs may help fight cancer

- Published

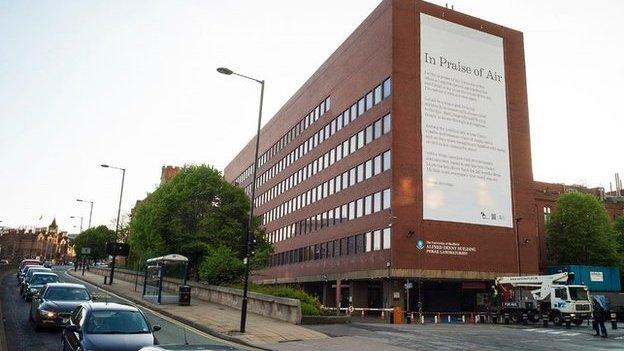

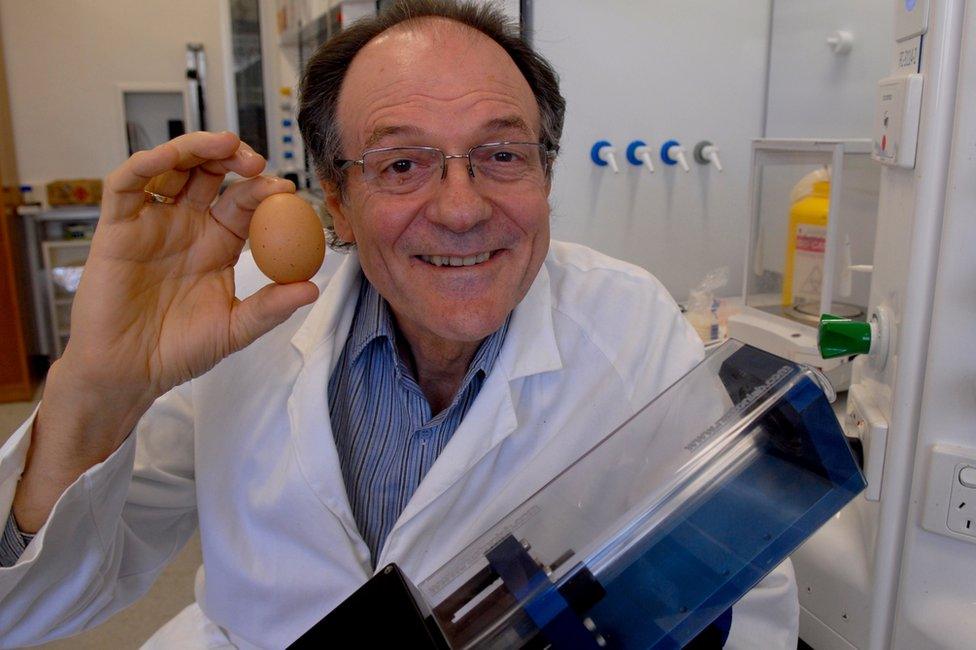

Prof Raston and his Vortex Fluidic Device, which successfully unboiled egg whites

A machine that can "unboil" protein-rich egg whites, winning an Ig Nobel Prize in 2015, may also have important medical applications, its inventor says.

Prof Colin Raston, a chemist from Flinders University in South Australia, has discovered that his Vortex Fluidic Device (VFD) can also slice tiny carbon nanotubes (CNTs) to uniform length with unprecedented precision.

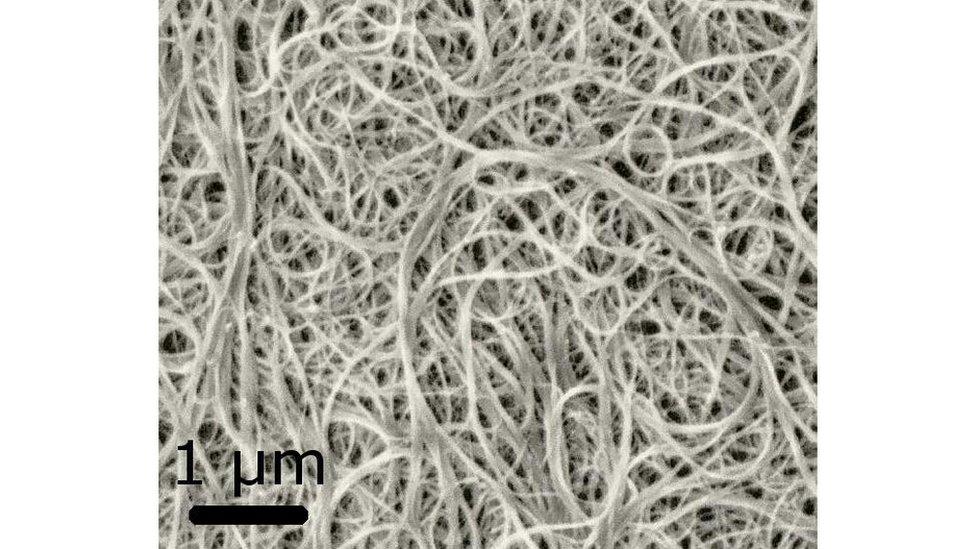

Individual CNTs, which are just a few nanometres in diameter or about the width of a small virus, have incredible properties - they are 200 times stronger than steel yet five times more flexible, and conduct electricity five times more efficiently than copper wires.

But an inability to consistently create nanotubes with uniform lengths and properties has been one of several obstacles that has frustrated scientists' efforts to harness these materials, which can be used for highly targeted drug delivery in cancer therapy.

"When you make CNTs normally, they're entangled - it's like a bowl of spaghetti. They're all stuck together and they're different lengths," Prof Raston told the BBC.

Shortening them currently requires toxic chemicals, which can chemically alter the surface of the CNTs, changing their properties and limiting their functionality.

Prof Raston's VFD, which mixes fluids inside a rapidly spinning glass tube, could offer a cleaner, faster alternative for cutting CNTs down to size, also opening up applications for electronics.

"What our device does is untangle the carbon nanotubes and then slices them, so you overcome two problems in one go," he says.

Carbon nanotubes resemble a "bowl of spaghetti" when created and must be cut down to size

Using just water, a liquid solvent, and a laser, his team was able to consistently produce CNTs with an average length of 170 nanometres, without degrading their properties. The results were published in Nature's Scientific Reports.

"It's one of highest tensile strength materials, and yet you put it in a liquid, and you spin it in a special way and with a laser you can cut it down," he says.

Prof Raston says his sliced CNTs are small enough for drug-delivery vehicles, and could also improve the efficiency of solar cells.

Eureka moment

The idea for the VFD was conceived on a 15-hour flight from Los Angeles to Sydney in 2010. Prof Raston wanted a small machine to use for continuous flow processing, a type of manufacturing where chemical reactions take place between fluids mixing inside a tube.

"It was a eureka moment," recalls Prof Raston. "I came up with the idea for the device, and I drew the plans on the plane."

The VFD has what looks like a glass test tube, about 20mm in diameter, tilted at a 45 degree angle. This tube is spun at very high speeds, up to 9,000 revolutions per minute.

"While you're spinning it, you actually add liquid to the bottom of the tube through stainless steel jet feeds," explains Prof Raston. "The speed of the spinning tube coupled with the incoming flow creates intense, highly dynamic micro-mixing."

The Vortex Fluidic Device kinks the nanotubes so they can be cut to precise lengths by a laser

This mechanical energy means the machine can create bio-diesel without adding any heat, and can also unravel and correctly fold proteins, he says.

Prof Raston and his colleagues demonstrated protein unravelling by successfully unboiling an egg, reverting gelatinous whites back into liquid form. It was an achievement that in 2015 earned the research team an Ig Nobel Prize for Chemistry.

The tongue-in-cheek Ig Nobels honour scientific research that seems unusual or funny at first glance but on closer inspection has merit.

That same protein-folding mechanical energy is what enables the device to manipulate CNTs: "Because of the complex way the liquid moves it has intense shear [force], and therefore it bends the nanotube," says Prof Raston.

This creates a kink in the structure - with the nanotube bent, his team added vibrational energy, using a near-infrared laser to slice through the weakened kink where the tube was folded.

Like a washing machine

Assoc Prof John Stride from the University of New South Wales in Sydney is an expert in carbon nanostructures, and says "if the researchers can reliably slice the CNTs 'to order' then this is a real advance".

"Anything that allows us to control and manipulate these nano-objects will be of use in developing applications," he says.

"The beauty of the approach is the relative low-tech aspect of it essentially being a spinning column of liquid that does the initial work… with a near-infrared laser providing the energy to cut the tubes.

"It's almost like laundry in the washing machine being spun out… it's very simple to picture what's happening, but of course that's occurring on the molecular scale, which is really quite intriguing."

Prof Stride also says that, if they're proven to be inert, shortened CNTs may provide an "effective mechanism for drug delivery to the inner cell region".

"It's a nice finding. I don't think it will completely revolutionise carbon nanotube research, but it's a significant advance in the field."

- Published15 May 2014