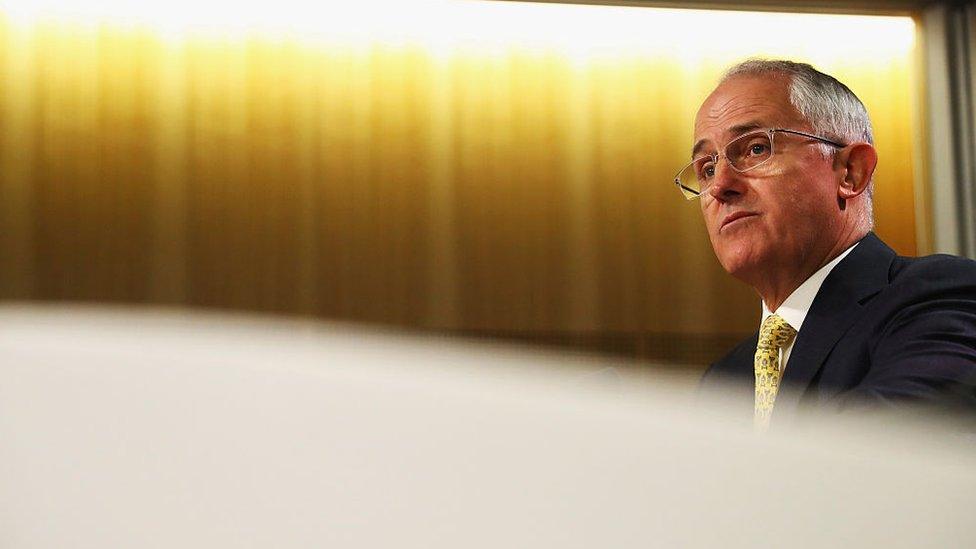

Can Australian PM Malcolm Turnbull form a government?

- Published

Malcolm Turnbull has accepted responsibility for the election results

Will Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull be able to form a government, or is the country on course for its fifth leader in three-and-a-half years?

Speculation, apprehension and more than a whiff of retribution. It is not the outcome Australians expected when in their millions they cast their ballots in Saturday's federal election.

But three days later, the result remains unclear and no-one is sure who will form the next government, or how, or when.

Neither of the major parties have so far won enough seats to claim an outright win as counting continues in around a dozen tightly-contested constituencies. They will decide this federal election that was fought on the promise of stability but has delivered, in the short-term at least, turmoil.

The Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull, who leads the centre-right Liberal-National Coalition, says he is confident of winning a majority. He may just squeeze home but his leadership could be damaged beyond repair.

After all, it was the millionaire former merchant banker who gambled on dissolving both houses of the Australian parliament (the first so-called Double Dissolution election since the late 1980s) and calling an early poll.

Frustrated at the refusal of the Senate, the upper chamber, to pass key labour reforms, Mr Turnbull went to the country, but has been left clinging to power as anger within his governing coalition intensifies.

For the first time in decades, all lower and upper houses were being contested in a single election

He is an accomplished media performer, as you might expect from a former journalist and lawyer, and came to the highest office last September, ousting Tony Abbott in a sensational party room coup.

The new man at the helm of the conservative government appeared to promise a more progressive approach than the pugilistic ways of his predecessor.

There would, his supporters hoped, be bolder policies to combat climate change in a country heavily reliant on coal (with one of the highest per capita rates of carbon pollution), and decisive action on a republic (Britain's Queen Elizabeth is the head of state here) and same-sex marriage.

But there was to be no grand theatre of reform. Was Mr Turnbull a hostage to right-wing factions within his government that were keeping him in the job, or was he biding his time waiting for an unequivocal mandate from the people?

There has, though, been no concrete endorsement from voters in an election fought mostly over jobs, health care and education. But the decisive swing against the conservatives has not seen a corresponding surge in public support for their main rival, the Labor opposition. Far from it.

While it has done better than many of its strategists had dared dream, it has almost no chance of forming a majority government. In recent years the party had self-destructed through repeated bouts of infighting as previous Labor prime ministers, Julia Gillard and Kevin Rudd, took it turns to knife each other in the back.

Opposition Leader Bill Shorten has repeatedly called on the prime minister to step down

Although the current leader, Bill Shorten, harbours ambitions of forming a minority government, he might be best off losing this time around and sitting back and watch a weakened Mr Turnbull lead either a nervous government with a waver-thin majority or a potentially fractious one dependent on minor parties and independents.

Labor could then agitate and destabilise from opposition, and then go on to win big at the next election.

That, however, supposes that the traditional two-party system in Australia is in good health. It isn't. Minor parties and independent candidates have attracted record support in this election.

They may be a disparate and controversial bunch, who variously support tough anti-gambling policies, banning the burqa in public places and voluntary euthanasia, but millions of voters consider them to be politicians with convictions, free of what newspapers here have described as the "all-consuming narcissism" of the main parties.

Voters have raged against the two heavyweights like never before.

There are fears that Australia could lose its AAA credit rating if the current gridlock hampers the government's ability to reform the economy as a long mining boom comes to an end.

Politics in Australia is a volatile business, and there have been four prime ministers in the past three-and-a-half years, yet the economy continues to grow and its fundamentals seem strong, despite the lack of political stability in recent years.

Elsewhere, life goes on in other countries with hung parliaments and dysfunctional governments.

Australia may find itself back at the polls if the impasse can't be resolved as a new type of politics emerges, one fuelled by voters who feel disenfranchised and betrayed by the old order.

On morning radio, a government minister said that as a child he used to laugh at the regular changing of leaders in Italy, but now the joke is on Australia.

- Published5 July 2016

- Published5 July 2016

- Published4 July 2016

- Published4 July 2016

- Published30 June 2016