Platypus venom paves way to possible diabetes treatment

- Published

Scientists can now synthesise the chemical so do not need to catch more platypuses

Platypus venom could pave the way for new treatments for type 2 diabetes, say Australian researchers.

The males of the extraordinary semi-aquatic mammal - one of the only kind to lay eggs - have venomous spurs on the heels of their hind feet.

The poison is used to ward off adversaries.

But scientists at the University of Adelaide and Flinders University have discovered it contains a hormone that could help treat diabetes.

Known as GLP-1 (glucagon-like peptide-1), it is also found in humans and other animals, where it promotes insulin release, lowering blood glucose levels. But it normally degrades very quickly.

Not for the duck-billed bottom feeders though. Or for echidnas, also known as spiny anteaters - another iconic Australian species found to carry the unusual hormone.

Both produce a long-lasting form of it, offering the tantalising prospect of creating something similar for human diabetes sufferers.

Insulin regulates blood sugar levels and is either insufficient in diabetics or their bodies do not react properly to it

Lead researcher Prof Frank Grutzer told the BBC's Greg Dunlop why the researchers had decided to look at the platypus and its insulin mechanisms: "We knew from genome analysis that there was something weird about the platypus's metabolic control system because they basically lack a functional stomach."

They are not the only animals to use insulin against enemies. The gila monster, a venomous lizard native to the US and Mexico, and the geographer cone, a dangerous sea snail which can kill entire schools of fish by releasing insulin into the sea, both also weaponise the chemical.

"That's obviously something that can be powerful in venom," Prof Grutzer said, though he stressed it was not what had led them to the discovery. "It was really coincidental," he said.

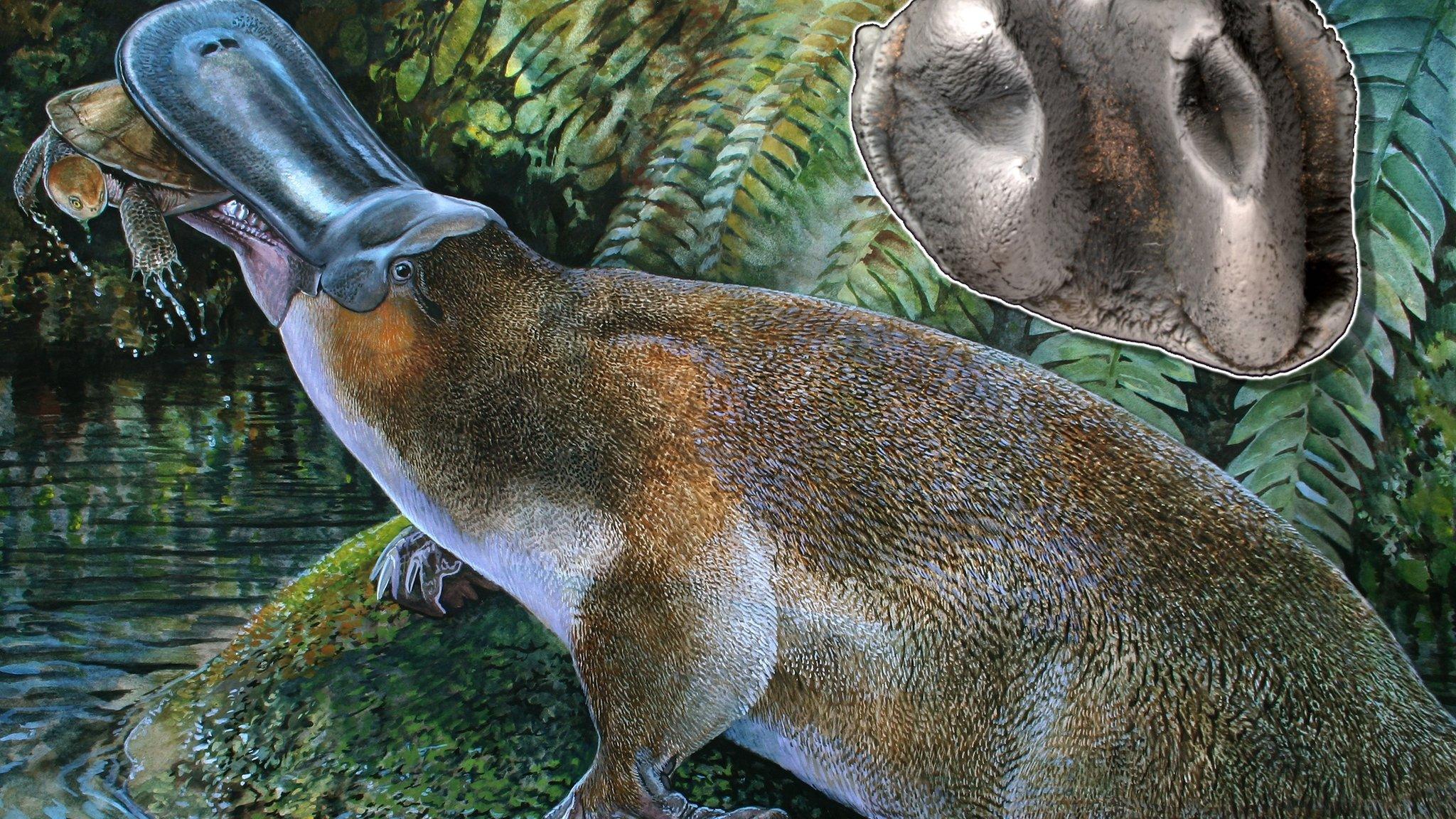

The mammal is often dubbed the oddest in the animal kingdom

He emphasised that much more research was needed before the discovery could, if ever, lead to a human treatment: "An important experiment is going to be putting this it into mice and see how it affects blood glucose levels. That's certainly very high on our priority list.

"But to get to a drug is a very long journey. We still have to learn a lot more about how this platypus hormone actually works."

- Published18 October 2013

- Published4 November 2013