Child abuse: Documenting Australia's shame

- Published

In Australia, a boy of 10 is raped by an Anglican clergyman, who cuts his victim with a small knife and smears blood over his back in a twisted ritual to symbolise the suffering of Christ.

This happened in the 1960s in Cessnock, a former mining town in the New South Wales Hunter Valley, but only now has this and other decades-old stories of sexual violence and degradation been heard, catalogued and, crucially for many victims, believed.

The Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse, external is an unprecedented investigation into an epidemic of depravity across Australia.

The far-reaching inquiry began in 2013 and has heard from thousands of survivors of paedophiles who worked, or volunteered, in sporting clubs, schools, churches, charities, childcare centres and the military.

It has the power to look at any private, public or non-government body that is, or was, involved with children. The Commission's task is to make recommendations on how to improve laws, policies and practices to protect the young.

To date, it has held more than 6,000 private sessions, along with several high-profile public hearings.

Paul Gray told investigators that between the ages of 10 and 14, he was sexually assaulted by Father Peter Rushton in Cessnock every one or two weeks. Sometimes, his attacker had an accomplice.

"I was chased by two men to the edge of the cliff and I hid in the bushes.

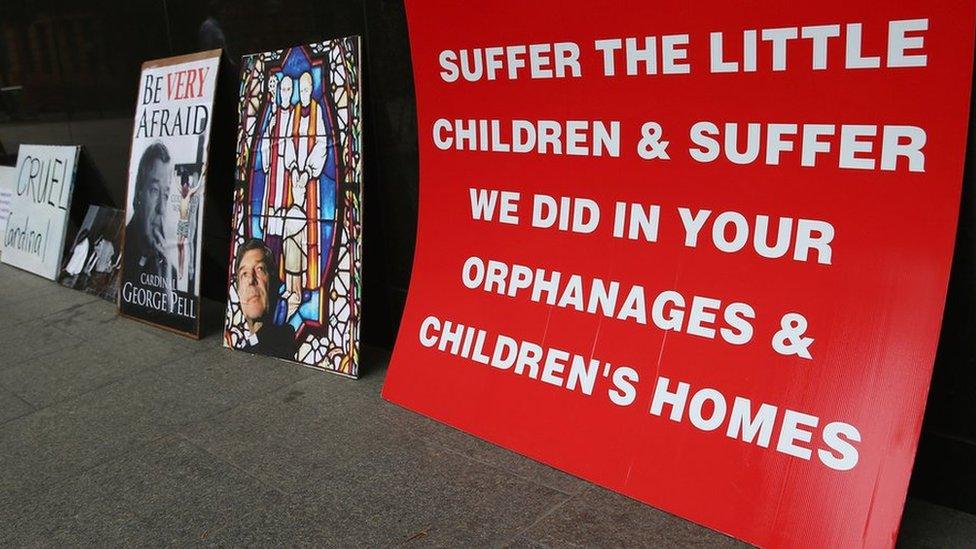

Cardinal Pell was questioned over what he knew about sex abuse by Australian priests

"After a while they dragged me from the bushes and I was raped by the two men, and while I was being raped I could hear another boy screaming," said Mr Gray, fighting back tears as he recounted memories that have burned inside him for half a century.

Too ill to travel from the Vatican to Sydney to give evidence, Australia's most prominent churchman, Cardinal George Pell, was questioned via video link by the Royal Commission over what he knew about alleged abuse and cover-ups within the Catholic Church.

For four days earlier this year, the senior Vatican official was quizzed, denying any personal wrongdoing but conceding the organisation had made grave errors.

"I am not here to defend the indefensible," said Cardinal Pell. "The Church has made enormous mistakes, is working to remedy those, but the Church has in many places - certainly in Australia - mucked things up."

When he was 13, John Ellis, a former altar boy, was molested by an Australian monk who was also implicated in a suspected paedophile ring at a former Catholic boarding school in the Scottish Highlands.

Now a solicitor, Mr Ellis works with other victims, and we meet at a public hearing held by the commission on the 17th floor of Governor Macquarie Tower that stands over central Sydney.

As well as giving evidence to the commission about the abuse he suffered as a child, John Ellis supports other victims

Presiding over the session is the chief royal commissioner, Justice Peter McClellan, a judge of appeal in New South Wales. He is one of six commissioners; two women and four men, and they include a former Queensland police chief, a consultant child psychiatrist and a retired federal politician.

They have fanned out across Australia to document a nation's shame.

"The most important thing for people in being invited to give their own stories and having their stories valued is that somebody cares," Mr Ellis told the BBC news website.

"For many, many years people have been silenced, people have been fearful of what reaction they will get if they were to tell their truth. The overwhelming emotion people have when they have had that opportunity is empowerment."

When it hands down its final report at the end of 2017, this painstaking inquiry will have lasted for almost five years. Already, more than 1,700 cases have been referred to the authorities, including the police.

More prosecutions will almost certainly follow, but many victims will never savour justice.

The commissioners are due to publish their findings at the end of 2017

Dr Wayne Chamley, from Broken Rites, a group that gives a voice to the abused, said decades of brutality had left a terrible legacy.

"When you look at the rate of suicide for men who had these experiences and compared it with age-matched data from the coroners' courts, their risk factor is 20 to 40 times higher for suicide," he explained to the BBC.

"There are townships where there have been waves of suicide with hundreds of men. [In] Ballarat [in Victoria state], at least 50 or 60 suicides across just three classes in the primary school - just three classes of boys who became men. Bang. Devastating."

Gerard McDonald, 52, is a survivor of abuse, and one of thousands of people who have told their stories to the commission. His attacker, a Catholic priest, has spent 14 years in prison for attacking 35 boys.

"After every other altar boy practice in 1975, before dropping me home Father (Vincent) Ryan would sexually abuse me. All I could do was think about running to my mate's place and getting the biggest two knives he had and killing him," he said.

While this harrowing process is undoubtedly cathartic for Australia - and it's inevitable that legislation and procedures will eventually change to make children safer - campaigners insist many youngsters today still remain at risk from predators in institutions, while paedophiles stalking the internet continue to groom the vulnerable.

- Published22 June 2016

- Published2 March 2016

- Published29 February 2016

- Published27 September 2015