Adani Carmichael: Fierce debate over monster coal mine

- Published

It would be one of the biggest mines on the planet, occupying an area nearly three times larger than Paris, where world leaders hammered out a landmark agreement to combat climate change in late 2015.

If the A$16.5bn (£10bn; $12.5bn) project goes ahead in Queensland's Galilee Basin - and latest indications are that it will - the coal produced there will emit more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere every year than entire countries such as Kuwait and Chile, claim its opponents.

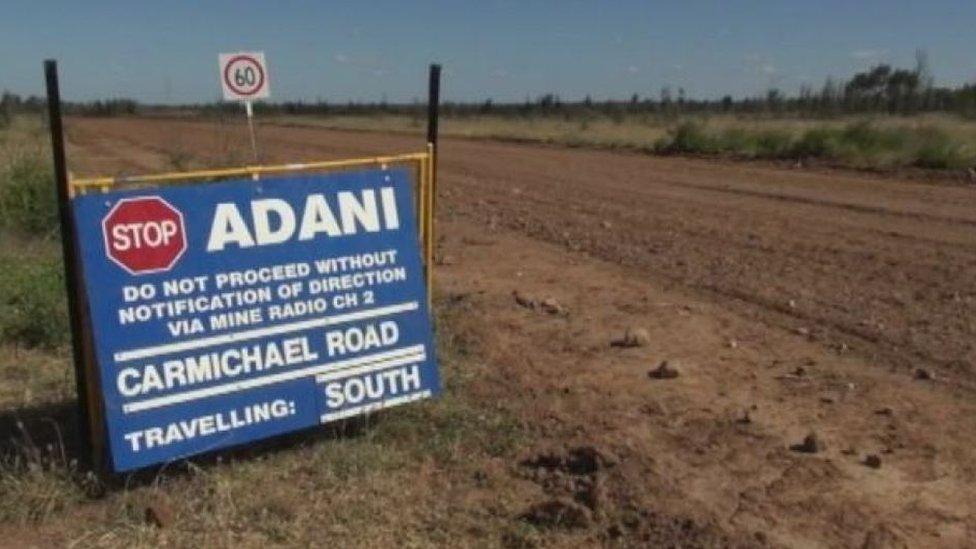

Delayed for six years by a stream of legal challenges and environmental impact assessments, the so-called Carmichael mine - to be developed and operated by the Indian mining giant Adani - has polarised Australians.

Supporters, who include local communities, the federal and Queensland governments, and, naturally, the resources industry, insist that it will bring jobs and prosperity to a depressed region of Queensland.

Critics, on the other hand, among them environmentalists and climate scientists, warn that the 60m tonnes of coal to be dug up annually from Carmichael's 45km (28-mile) pits will exacerbate global warming and threaten the already ailing Great Barrier Reef.

They also say Australia is out of step with international moves to decrease reliance on fossil fuels, in line with the Paris agreement to limit average temperature rises to "well below" two degrees above pre-industrial levels.

India itself recently forecast that 57% of its electricity would come from renewable sources by 2027. Britain plans to close all its coal-fired plants by 2025, while Canada aims to do so by 2030.

In Australia, by contrast, the conservative government is talking up "clean coal" - a commodity most experts consider a pipe dream - and attacking renewable energy as unreliable and expensive. It has also ruled out any kind of emissions trading scheme.

Does coal have a place?

Already the world's biggest exporter of thermal coal (the type used to generate electricity), Australia is now eyeing new markets in Asia.

In collaboration with Japan, which manufactures power stations, it is "actively encouraging developing countries such as Vietnam, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh to build new coal-fired generators so we can sell coal to them", Richard Denniss, chief economist at the Australia Institute, a progressive think-tank, told the BBC.

With its long gestation and massive scale - six open-cut and up to three underground mines sprawling across 250sq km of arid landscape, with the entire operation engulfing almost twice that area - Carmichael has become a flashpoint for pro- and anti-coal forces.

Adani has already spent A$1.3bn on the Carmichael mine project

The former contend that its coal will provide millions of Indians with cheap, reliable electricity, lifting them out of "energy poverty". Royalties from the mine will also give a much-needed boost to the Queensland government's finances.

The latter see it as a symbol of Australia's reluctance to commit to the radical action which scientists say is required to prevent dangerous levels of warming.

Frank Jotzo, director of the Australian National University's Centre for Climate Economics and Policy, warns: "The opening up of new mining areas like the Galilee Basin is fundamentally incompatible with the global goal of well below two degrees."

Like others, Prof Jotzo is unconvinced by arguments to the contrary. For instance, Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull - who has called coal "a very important part... of the global energy mix and likely to remain that way for a very long time" - has said that developing Carmichael would not push up global supply.

Mr Turnbull has also said that, far from reducing global emissions, calling a halt to Australian coal exports could actually increase them, since the likes of India would import dirtier coal from elsewhere.

'Clean' coal argument

According to the Australia Institute, the quality of coal in the Galilee Basin - an area bigger than the United Kingdom - is among Australia's poorest. ("Dirty" coal has a lower energy content, meaning more of it has to be burnt.)

The federal Environment and Energy Minister, Josh Frydenberg, claims there is a "moral case" for Australia to supply coal to developing nations.

Protesters opposed to the mine rally in December

Others point to the serious health costs of pollution caused by burning coal, and to forecasts that climate change will hit the world's poorest hardest. Critics also say solar energy could power remote Indian villages more easily and cheaply.

Until relatively recently, some were predicting that Adani would walk away from the Galilee, frustrated by funding difficulties, the lengthy environmental assessments and the court actions, one of which concerned the mine's impact on the yakka skink, an endangered reptile.

One by one, though, the company has cleared the regulatory hurdles, albeit with 190 state and 36 federal conditions now attached to the project.

Last December came the high-profile announcement that the last major element had been approved: a rail line to transport coal from the mine, 400km inland, to the export terminal, near the Great Barrier Reef.

An Adani spokesman notes that the company has already spent A$1.3bn on the project, including more than A$100m on legal fees - "without putting one shovel in the ground". Those figures, he says, "show the company's commitment".

Lately, opposition has focused on news that the federal government is considering giving Adani a cheap A$1bn loan to build the rail link - infrastructure which some fear could become a "stranded [obsolete] asset".

Adani founder Gautam Adani (left) with Australia's then Trade Minister Andrew Robb and Rio Tinto's ex-CEO Sam Walsh in 2015

Prof Jotzo told the BBC: "It's questionable whether this mine will still be a viable proposition in two decades' time, whereas infrastructure such as a rail line or port expansion [also planned by Adani] would have a lifetime of 50 to 100 years."

With construction of the mine expected to begin by late 2017 - assuming final legal appeals, including one by a local indigenous landowners' group, are rejected - activists are gearing up for a campaign of mass protests.

One of the biggest issues galvanising opponents is the potential impact on the Great Barrier Reef, both indirectly through intensifying climate change, and directly through dredging of the seafloor to expand port facilities and increasing shipping across the reef.

As for jobs, Adani's own economist has admitted in court that, rather than creating 10,000 positions, as the company has promised, the mine will employ fewer than 1,500 people.