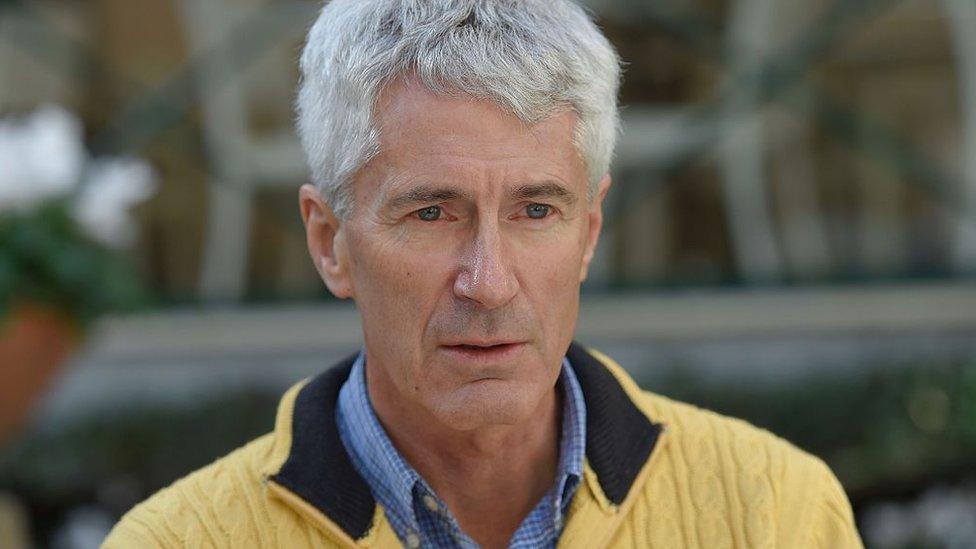

Anthony Foster: Tireless fighter against Catholic sex abuse

- Published

Anthony Foster's advocacy helped launch an inquiry into institutionalised sexual abuse

Clutching a photo of two smiling girls, Anthony Foster last year delivered a powerful statement about what had become his life's mission.

"These are my girls," he said before television cameras in Rome.

"A Catholic priest was raping them when this photo was taken so that's why we've been fighting for so long... This was my perfect family. We created that, the Catholic Church destroyed it."

That fight occupied much of his final two decades. Mr Foster died in hospital at the weekend not long after suffering a fall at his home in Melbourne. He was 64.

Along with his wife, Chrissie, Mr Foster had relentlessly pursued the church for answers since his daughters, Emma and Katie, were abused at their primary school between 1988 and 1993.

Emma later endured drug addiction and self-harm. In 2008, aged 26, she overdosed on medication and died while holding a teddy bear she had received on her first birthday.

In 1999, Katie was struck by a drunk driver, leaving her with physical and mental disabilities which require constant care.

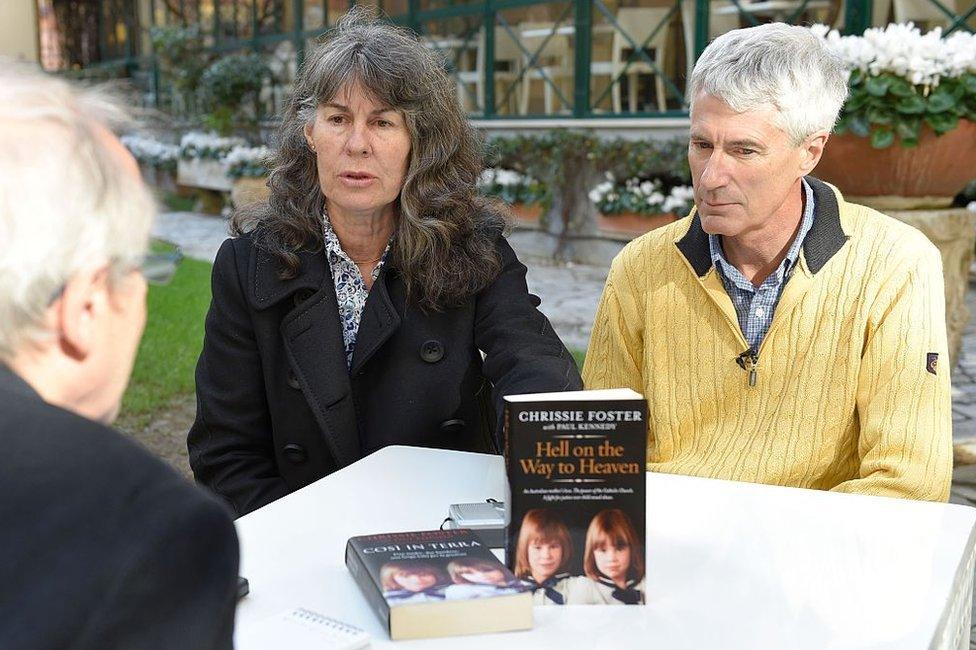

Mr Foster with his wife, Chrissie, in Rome last year

The Fosters had long sought answers about their daughters' abuser, Father Kevin O'Donnell, a paedophile priest who had been the subject of allegations as early as 1958. He was jailed for child sex offences in 1995 and died in 1997.

The Fosters said their family's accounts were not initially believed by the church. Finally, after a 10-year legal battle, the Fosters received A$750,000 (£435,000; $555,000) in a settlement.

"The church should be ashamed," Mr Foster said in an interview, external with Fairfax Media in 2010. "If it had been open about the abuse, Emma might have still been here today."

Although softly spoken, Mr Foster's eloquent words carried power as the pair gave interview after interview recounting their harrowing story.

In addition to seeking justice for their family and, increasingly, other victims, the Fosters educated parents and would-be parents about communicating with their children.

Their advocacy contributed to the formation of a royal commission - Australia's highest form of public inquiry - into institutionalised sexual abuse.

Set up in 2013, the inquiry is due to deliver its final report in December after hearing devastating personal accounts and a claim that 7% of Australia's Catholic priests abused children between 1950 and 2010.

It was long-awaited testimony from Cardinal George Pell, Australia's most senior Catholic figure and treasurer to the Vatican, which took the Fosters to Rome last year.

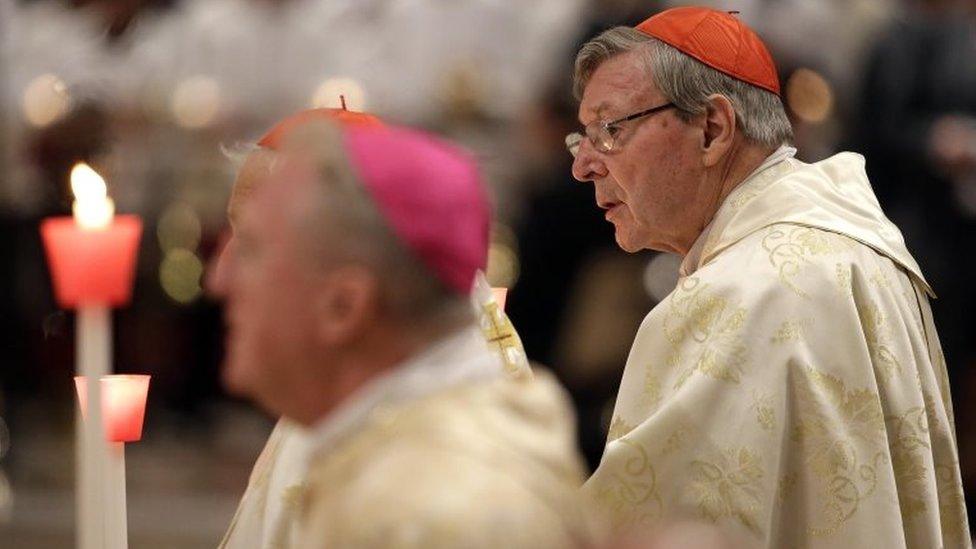

Cardinal George Pell gave evidence at an inquiry last year

Appearing via video link, Cardinal Pell, who was Archbishop of Melbourne from 1996 to 2001, gave evidence about whether he knew that abuse was occurring under his watch.

After one hearing, Mr Foster confronted the cleric and told him he was "holding the hand of a broken man".

Following Mr Foster's death, royal commission chair Justice Peter McClellan paid tribute to the family for helping to bring about the inquiry. He noted they had "attended hundreds of days of public hearings and participated in many of our policy roundtables".

"With a dignity and grace, Anthony and Chrissie generously supported countless survivors and their families whilst also managing their own grief," he said.

Victorian Premier Daniel Andrews said Mrs Foster had accepted the offer of a state funeral.

"History will record that a man named Anthony Foster quietly and profoundly changed Australian history," he said.

"He fought evil acts that were shamefully denied and covered up."

Paul Kennedy, a journalist who wrote a book with Mrs Foster, Hell on the Way to Heaven, said the nation had lost "a giant".

Mrs Foster wrote a book called Hell on the Way to Heaven

"Anthony Foster was my dear friend and hero. Goodbye, brave man," he tweeted.

In a statement, Mr Foster's family said they were humbled by his passionate efforts to protect children.

"Anthony's heart was so big - he fought for others to make sure what happened to our family, could not happen to anyone else," they said.

It had brought them peace to know that he had become an organ donor, "in line with Anthony's generosity in life and death".