'Real bodies' exhibition causes controversy in Australia

- Published

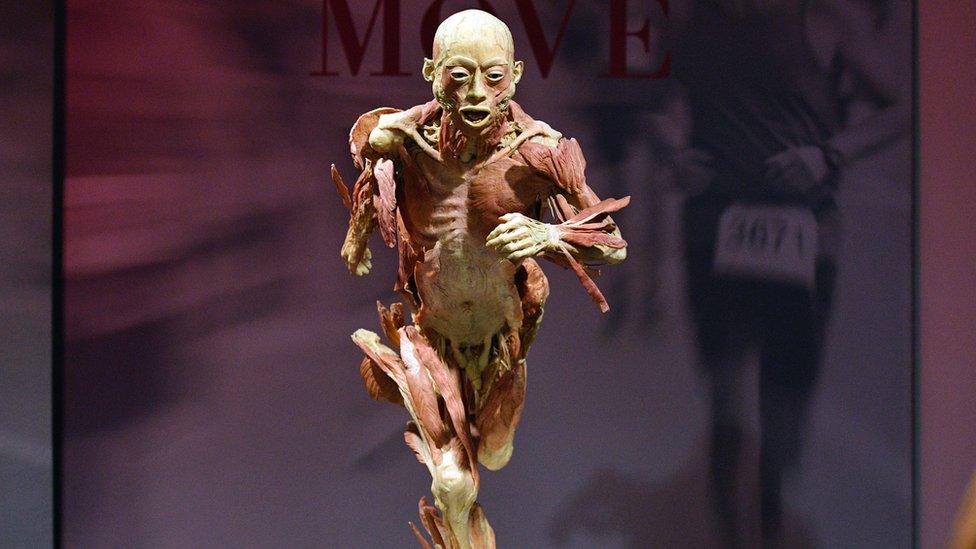

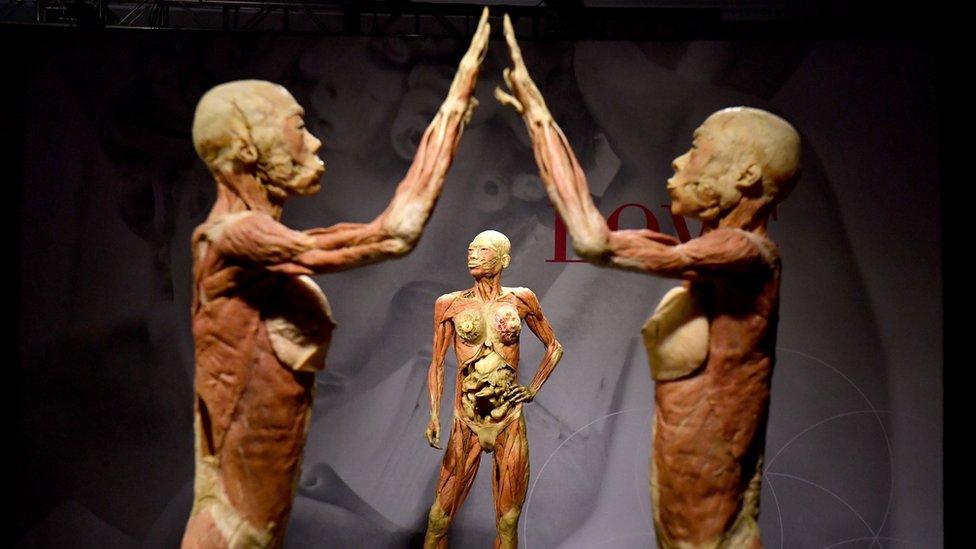

The exhibition is currently on display in Sydney

An exhibition of preserved human bodies has drawn controversy in Australia this week after an activist group raised questions about the origin of the specimens.

The group of objectors - who include doctors, lawyers and scientists - have called for the exhibition in Sydney to be shut down.

They assert that it may include the bodies of executed Chinese inmates, including political prisoners.

But the organisers of Real Bodies: The Exhibition have strongly denied those allegations, calling them "lies" and "sensationalism".

They say the 20 cadavers were legally provided by a medical university in China, where hospitals had determined them to be "unclaimed corpses".

WARNING: Readers may find some images in this article disturbing

The bodies have been preserved through a method known as plastination, which drains them of fluids before replacing them with silicone. This allows the skinned bodies to be exhibited in life-like poses.

What is the concern?

In an open letter to Australian politicians, the International Coalition to End Transplant Abuse in China says there is "credible evidence" that the bodies may belong to "executed prisoners and prisoners of conscience from China".

"We are astonished that visas and permits for bringing this exhibition into Australia were issued by the Australian Government, given the lack of documentation demonstrating ethical and legal sourcing of each body," the letter reads.

"No motivation for profit or political sensitivities could ever justify such a crass and undignified violation of human rights."

One signatory, Prof Maria Fiatarone Singh from the University of Sydney's medical school, told the BBC that the origin of the bodies - the city of Dalian - was a concern. She described Dalian as the "epicentre" for executions of prisoners associated with Falun Gong - a spiritual movement that is banned in China.

Prof Vaughan Macefield, from the University of Western Sydney, said he was troubled that the bodies had not been identified. He also noted that most appeared to be young men, whereas medical schools often have bodies donated from older people.

What do the organisers say?

Imagine Exhibitions chief executive Tom Zaller called the allegations "complete fabrications", saying the bodies had been sourced correctly from Dalian Medical University.

"We know for 100% fact that all of the specimens used died of natural causes, suffered no trauma, and were absolutely not prisoners of any kind," he told the BBC.

"We're not trying to promote 'hey pick up a body off the street' - this is a legal fact that they were all processed properly, legally and above board for an educational experience."

The company describes the exhibition as a blend of "art, science, and emotion as a museum of the self".

Mr Zaller said the company had satisfied all legal requirements in Australia, as it had it Europe, Asia and North America where it has previously held exhibitions of bodies.

Is plastination new?

No, exhibitions featuring bodies in this way have been shown across the world since the 1990s.

The plastination process can take up to a year for each body. It was invented by scientist Dr Gunther von Hagens, who started the Body Worlds exhibition. Like Imagine Exhibitions, its displays have been viewed by millions of people internationally.

Exhibitions by separate companies have been banned in France and Israel, primarily due to ethical concerns over the display of bodies.

New South Wales Health told the BBC it acknowledged "the serious concerns" raised by the open letter this week. However, it said the exhibition did not require a licence because it was not deemed to be using bodies for scientific or medical purposes.

How does science obtain bodies?

Standards and procedures vary around the world.

In Australia the use of unclaimed or unidentified bodies is illegal, said Rohan Long, a curator at the University of Melbourne's anatomy museum.

"People that want to donate their body to medial science in Australia have to be processed before their death," he said.

"There needs to be explicit statement of consent from the individual. It's not good enough to say that we just found the body."

He said ethical and legal guidelines were strict in science, adding: "When it becomes entertainment, that's when you get into shades of grey."

Beijing harvested organs from executed prisoners until 2015, when it ended the practice. Prisoners had accounted for two-thirds of transplanted organs, based on state media estimates.

- Published11 August 2015