Phillip Hancock: Rare foreign organ donor praised in China

- Published

Phillip Hancock is the first foreigner to be an organ donor in Chongqing

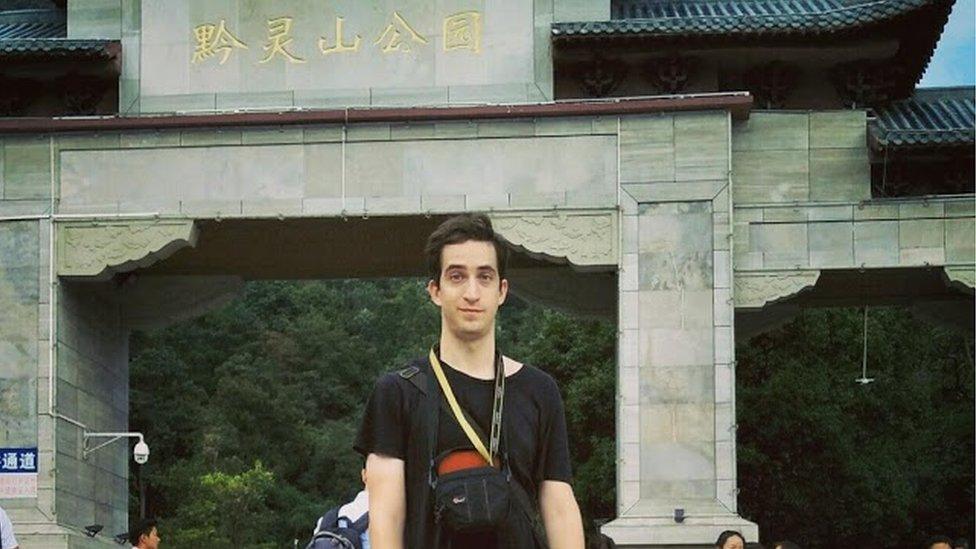

Phillip Hancock had been working as an English teacher in China when he unexpectedly fell ill and died last month. The posthumous gift of the Australian's organs has been lauded in China, a nation with few foreign donors, and changed five lives.

Mr Hancock, 27, died from complications related to type 1 diabetes in the city of Chongqing on 9 May.

According to the Red Cross Society of China, he became Chongqing's first foreign organ donor and only the seventh in the nation's history.

Mr Hancock's liver and kidneys were used in three life-saving operations. His corneas helped two people to see again.

Organ donation remains uncommon in China, which has one of the lowest donor rates in the world.

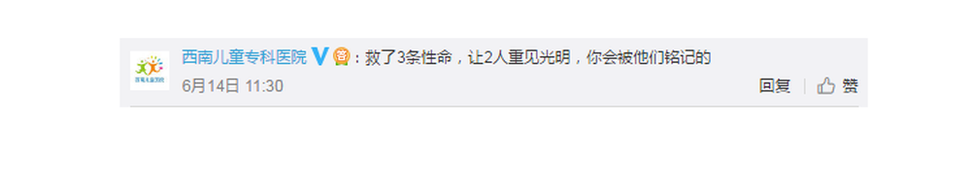

Mr Hancock's gift struck a chord with many Chinese on social media, with some calling him a "hero" and an "angel".

One online tribute reads: "You saved three lives and helped two others see. You'll always be remembered."

Another person wrote: "You'll live on through those you saved."

'Wanted to help in whatever way'

Mr Hancock had lived in China for four years when he fell ill from diabetes-related complications. When his family flew to his side, they found him in a coma in hospital.

Doctors told them that his heart had temporarily stopped beating on the way to hospital.

Tests taken at separate hospitals showed evidence of brain death, his father said.

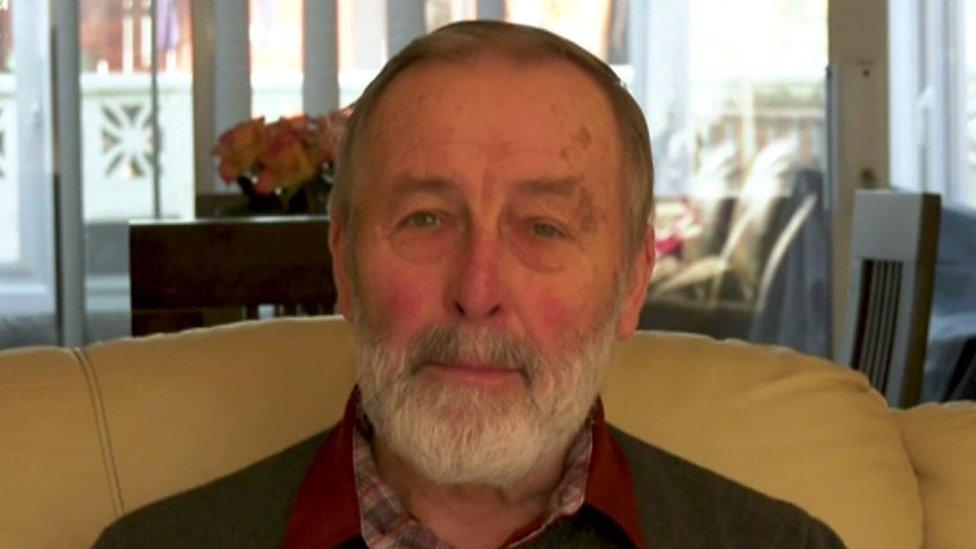

"There was nothing to be done," Peter Hancock told the BBC. "We knew he was gone, even though he was still warm to the touch and his heart was beating."

Messages on social media praised Mr Hancock's generosity

Doctors told the family that his organs would deteriorate the longer he was kept on life support.

"It was very hard, we had to make that decision [to switch off life support] sooner rather than later," Mr Hancock said.

"Most people don't talk about organ donations when they're alive, but thankfully Phil did talk about it.

"He had always thought that if he was ever in that situation, he would like his organs donated - whatever they could take - so he could help out in some way.

"He always wanted to help people in whatever way possible. That's why he wanted to be a teacher."

Donations in China

Reluctance in China about donating organs is related to a traditional belief that the body should remain "complete" after death, experts say.

"The idea that one's body as a whole - including its outermost skin and hair, given by one's parents, is not to be harmed - must be at the back of everyone's mind," said Associate Prof Yi Zheng, a cultural studies expert at the University of New South Wales.

People also harbour misconceptions about the organ donation process, said Dr Kelvin Ho from the Hong Kong Organ Transplant Foundation.

"They think that doctors will not try their best to save their lives if they have agreed to donate their organ after death," he told the BBC.

Fears around black market organ trading have also fuelled public suspicions. In 2015, China stopped harvesting organs from executed prisoners - a practice that had supplied two-thirds of transplanted organs.

It was no surprise that the government helped publicise Mr Hancock's story in state media, according to Dr Ho.

"It would have helped them to show the public that even non-Chinese are willing to be organ donors," he said.

Though overall rates remain low, Dr Ho said the number of organ donors in China had increased in recent years to more than 5,300 in 2017.

In an unrelated case, a woman pays tribute to an organ donor listed on a memorial in Harbin, China

The Hancocks said they have been overwhelmed by messages of gratitude, including by one recipient of their son's organs.

"He told us how grateful he was that Phil had been so generous. Phil had saved his life and given him another 40 years," Mr Hancock said.

Such messages had "helped a little" with his grief, he said.

"Some people have said to us: 'Try and not to be too sad because part of Phil is still living on in these people.'

"But as a parent, it's not much consolation. While we're glad he's helped these people, deep down, we just want him back."

- Published14 May 2018

- Published26 February 2018