The challenge of 'farming the desert' in Australia

- Published

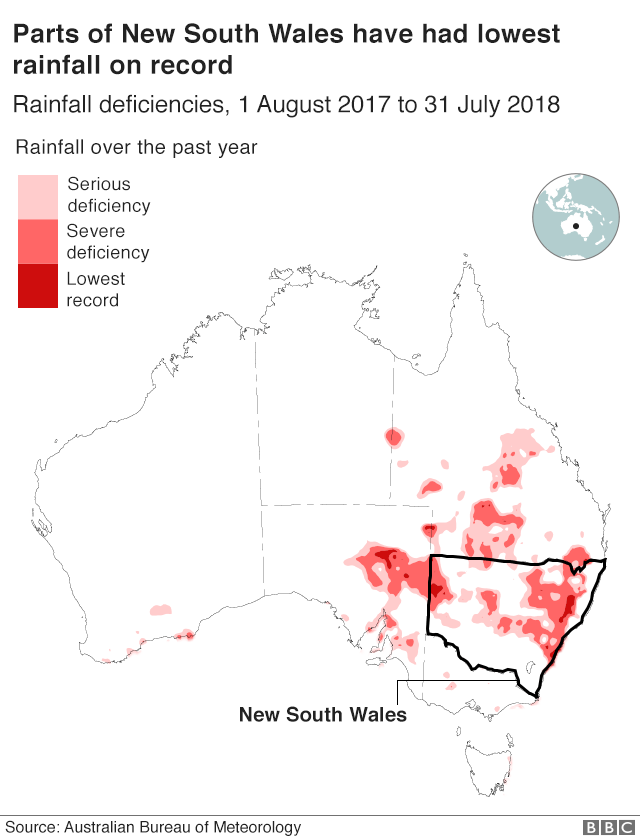

The entire state of New South Wales is currently drought-affected

The plight of drought-hit farmers in Australia has prompted an outpouring of sympathy across a country that has long mythologised the inhospitable "bush" and its inhabitants. But it has also raised questions about subsidising those eking a living in agriculturally marginal areas, writes Kathy Marks in Sydney.

Mellissa Conomos runs beef cattle on a 300-acre property in Gunnedah, in north-western New South Wales. This year, her dams are dry and her paddocks are bare. "They're living on dirt," she says.

"Even the weeds are gone. You've got sheep walking away from newborn lambs because they know they've got no chance of raising them."

Gunnedah has been hard hit by the prolonged dry weather crippling eastern Australia, which is being compared to the "Millennium Drought" that scorched the country during the 2000s.

Ms Conomos is hand-feeding her animals expensive trucked-in hay. She has had to sell half her black Angus herd, along with 30 sheep.

"Some people are feeding orange peel to their cattle, that's how desperate it's getting."

With little or no rain in recent months, the whole of NSW has been declared in drought, together with 60% of Queensland.

Images of caked paddocks and starving animals have horrified Australians, and the new Prime Minister, Scott Morrison, has named drought relief as the nation's "most urgent and pressing need right now".

In recent weeks, the federal government has announced extra household assistance for farmers, bringing the total aid bill to A$1.8bn (£1bn; $1.3bn) - although this includes some low-interest loans.

Drought 'in many ways predictable'

The poet Dorothea Mackellar called Australia "a sunburnt country, a land … of droughts and flooding rains". Seventy per cent of the mainland is classed as arid or semi-arid, external, meaning it receives less than 500mm of rain annually.

Just over half of Australia is used for agricultural production, external. However, even in good years when the rain buckets down, crop yields are significantly lower than elsewhere.

Resourceful and innovative, most farmers make a reasonable living, maximising their returns in good times and planning for drought by putting aside cash, storing fodder and destocking.

Others, less efficient or battling more rugged conditions - attempting to "farm the desert" as some critics say - struggle, but mostly hang on. Many are reluctant to leave farms that may have been in their families for generations.

"The reality is that the Australian climate is extremely variable, with extended periods of drought," says John Daley, chief executive of the Grattan Institute, a think tank.

"The current conditions are not extraordinary. So if you're not surviving a drought, which is in many ways very predictable, you have to ask why."

Many farmers say this drought has been their worst. But Mr Daley contends that farmers - who receive transport subsidies and low-interest loans, among other government assistance - should be treated no differently from other business owners.

Thirsty cattle swarm around a water truck in New South Wales

"The fundamental question here is: what's so special about farming? We've seen car manufacturing and other industries go to the wall in Australia on the basis of economic rationalist arguments. What we wind up doing is bailing out those farmers who are least able to cope."

'Part of our national identity'

Lately, the agricultural skills of Aboriginal Australians have been highlighted by indigenous historians such as Bruce Pascoe, who in his 2014 book Dark Emu detailed how, pre-colonisation, the country's first inhabitants grew crops and conserved soil, water, wildlife and fish.

The land was then degraded by Europeans' hoofed livestock and intensive farming techniques, he wrote.

Today, Australian agriculture is worth more than A$63 billion (2016-17), external, with more than three-quarters of output exported, external. Outsiders are often astonished to learn that the nation's agricultural products include water-thirsty cotton and rice. Many farmers rely on irrigation, and there is a thriving water market.

Linda Botterill, a professor of public policy at the University of Canberra, says farming is "part of our national identity", with public affection for farmers common "right across demographics and voting intentions".

That affection is clear from the countless "sausage sizzles" and other fundraising events being held in communities across Australia. One supermarket chain, Coles, matched customers' drought aid donations, dollar for dollar, during August.

Children in rural Australia say drought has taken a toll on their schooling and family life.

Mr Morrison's predecessor, Malcolm Turnbull, defended additional public funds for drought relief as aimed at relieving household poverty rather than propping up failing businesses. "It is designed to keep body and soul together, not designed to pay for fodder," he said.

However, Peter Harris, chairman of the Productivity Commission, the federal government's main economic advisory body, told the Sydney Morning Herald, external last week that decades of drought assistance totalling billions of dollars had done little to help farmers, and similar measures, if taken now, were "condemned to fail".

Farms of the future

The challenges facing farmers are set to become more acute, with climate change bringing more frequent and severe droughts, altering rainfall patterns and making more land agriculturally marginal or unviable, say scientists.

The opposition Labor Party's agriculture spokesman, Joel Fitzgibbon, has warned Mr Morrison that he will "fail farmers" unless he acknowledges climate change as a factor in the current drought and commits to "both mitigation and adaptation".

In order to meet future challenges, farmers need better data on weather, soil and drought-resistant crops, according to Prof Barry Pogson, a plant biologist at the Australian National University.

He is researching ways of manipulating genetic "switches" to send plants into survival mode quickly, then restore them to growth mode quickly when drought subsides, making them more productive.

Farmers are doing their best to make hay supplies last

John Freebairn, an economics professor at the University of Melbourne, believes farmers should decide where and how they farm.

"If they think they can push the margins out a bit further, with new technology or whatever, and are able to make a go of it, that's fine," he says. "But we shouldn't be subsidising them."

The current dry is worse even than the Millennium Drought, says Mellissa Conomos. "I've never seen the whole district so dry," she says, adding that suicide is a major issue in rural communities.

"Farming is always a gamble, but at the moment we're living day to day, just praying and hoping for rain. And it still hasn't come."

- Published26 August 2018

- Published9 August 2018

- Published2 August 2018