Malcolm Turnbull: The 'refreshing' PM felled by revolts and revenge

- Published

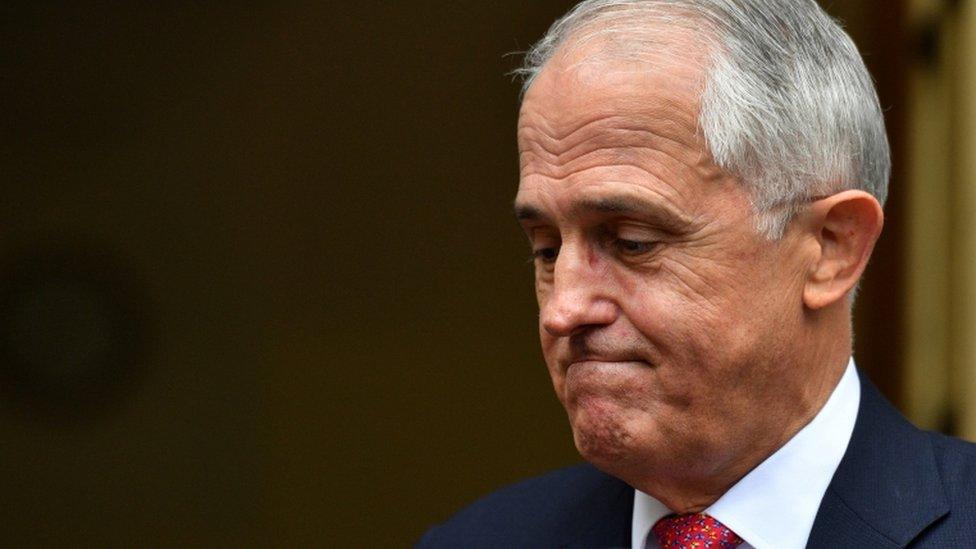

Malcolm Turnbull failed to live up to his promise as prime minister.

Malcolm Turnbull began his Australian prime ministership in 2015 by declaring it was the most exciting time to be alive. Achievements followed but, as political historian Paul Strangio writes, so too did reality - and it bit hard.

What madness has infected Australian politics and why did Mr Turnbull, whose ascension to the job aroused such initial optimism, end so badly?

Partly it can be explained by the primal political passion of vengeance.

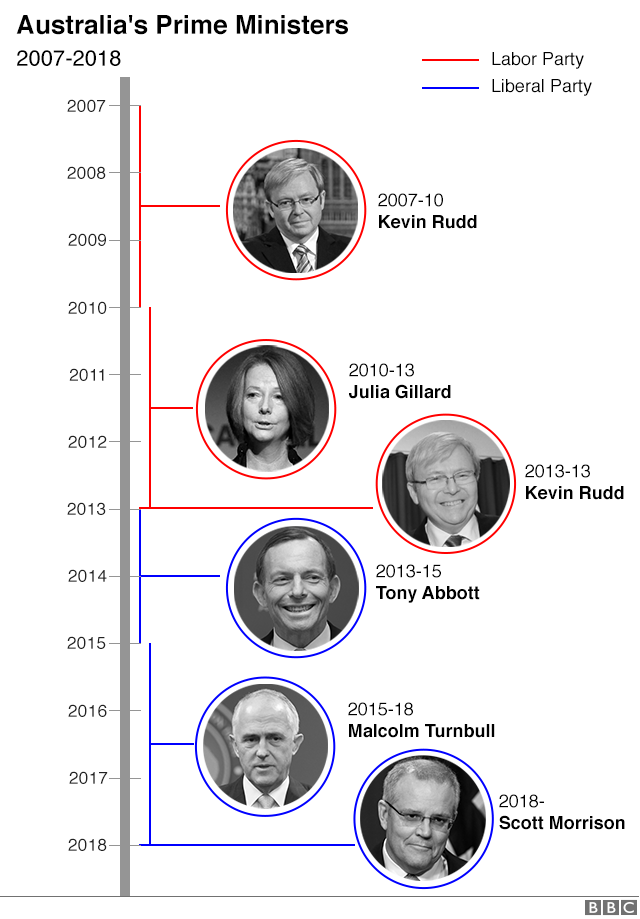

Malcolm Turnbull toppled Tony Abbott to become prime minister in September 2015.

As in the preceding Labor period of government when Julia Gillard felled Kevin Rudd as prime minister who thereafter waged a remorseless insurgency against her, Mr Abbott and his allies have been hell bent on retribution against Mr Turnbull since 2015.

On Friday, Mr Turnbull was overthrown by his Liberal Party colleagues in favour of his treasurer, Scott Morrison.

However Mr Turnbull's demise also has its origins in larger forces.

Rise unstoppable

Barrister, journalist, businessman, articulate and a renowned independent thinker, Mr Turnbull was long regarded as a coming man of Australian politics.

He entered the national parliament in a wealthy Sydney electorate in 2004 and served briefly as a minister in the final term of John Howard's Liberal-National coalition.

Malcolm Turnbull: How the party turned on Australia's PM

Following the Howard government's defeat by Mr Rudd's Labor Party in 2007, Mr Turnbull became the second of three Liberal opposition leaders.

He lost the position to Mr Abbott in an internal rebellion in 2009 that was catalysed by differences over climate change policy.

Mr Abbott and fellow conservatives bitterly resented Mr Turnbull's willingness to support the Rudd government's proposed emissions trading scheme.

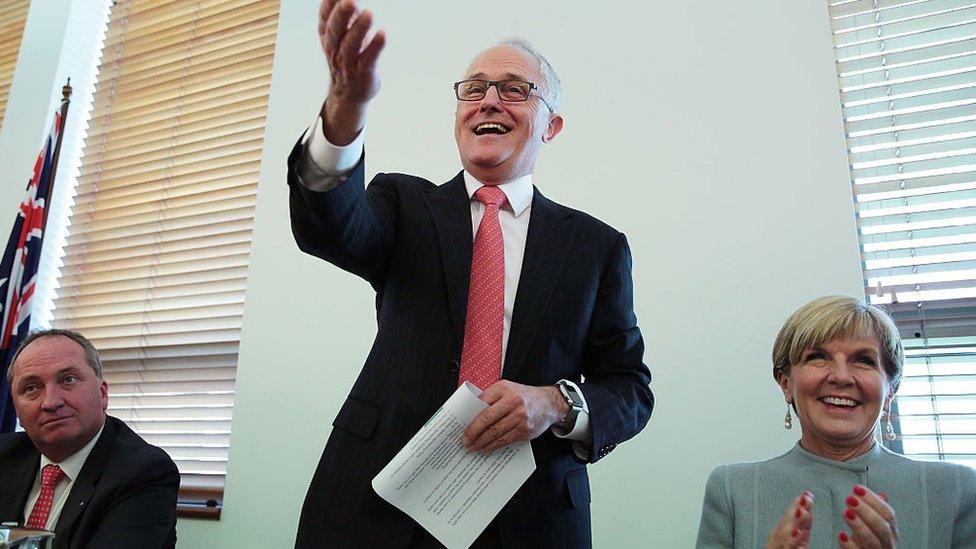

When in September 2015 Mr Turnbull had his revenge on Mr Abbott, who had proved a deeply unpopular prime minister, there was a contagious optimism surrounding his ascension.

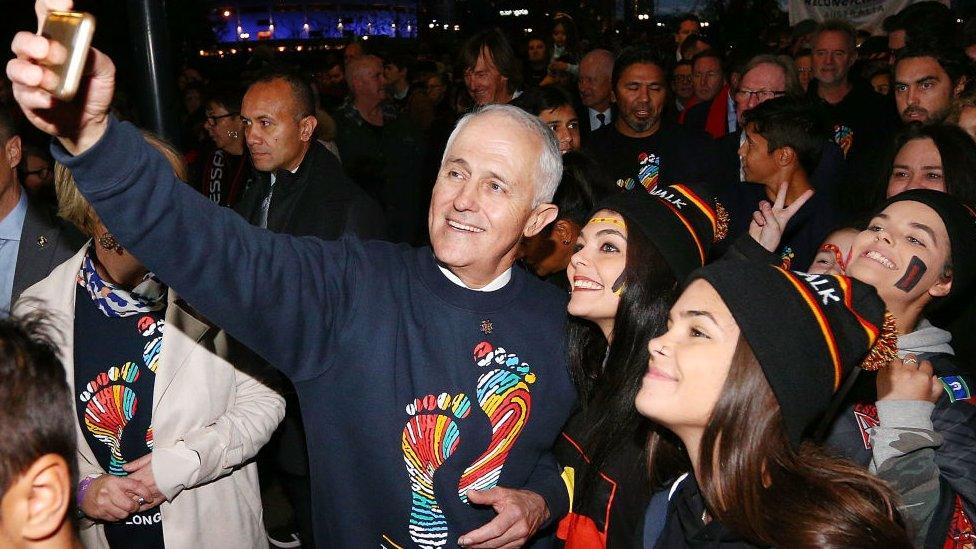

Mr Turnbull seemed a breath of fresh air following the dour muscular conservatism of his predecessor.

"There has never been a more exciting time to be alive and there has never been a more exciting time to be an Australian," he enthused.

He promised an "adult" conversation with the electorate rather than Mr Abbott's sloganeering. The public responded buoyantly: the government's and Mr Turnbull's personal ratings soared.

Party battle

A key aspect of Mr Turnbull's appeal in the electorate was that he was not regarded as a creature of his party.

Malcolm Turnbull was more popular with the electorate than his party, experts say

Autonomy between leader and party can be an asset for a PM in an era when major party bases are narrowing and there is growing divergence between residual party membership and majority public opinion.

It rapidly became apparent, however, that the dilemma facing Mr Turnbull was that to exercise policy autonomy from his party (particularly in totemic areas like climate change and same-sex marriage) risked internal revolt.

On the other hand, if he hewed closely to party views, especially to the more vocal conservative wing, he risked extinguishing his public popularity.

It was a dilemma Mr Turnbull never resolved.

Mr Turnbull's hope was that emphatic endorsement by voters at the 2016 election would deliver him the authority to assert himself within his government. It did not happen.

His popularity faltered as the initial expectations of him went unfulfilled and the constraints he was operating under grew manifest.

The result - the government scraping back with a one-seat majority in the July 2016 election and its upper house position worsened - was a major setback for Turnbull.

His authority, rather than enhanced, was diminished and his internal critics, not reconciled to his leadership and deeply distrustful of his progressive leanings, were emboldened.

Beholden government

The Turnbull government had achievements. It presided over a same-sex marriage plebiscite and legalisation of same sex marriage, albeit via a private senator's bill.

Cheers and a sing-song: Turnbull's government achieved same-sex marriage

It refined school education funding, legislated tax cuts, and claimed credit for strong employment growth.

But the abiding impression was of a hedged prime minister who was consistently placating conservative opponents who would never be appeased.

As has been the case in Australia for two decades, action on climate change remained anathema to conservative warriors.

Mr Turnbull's twists and turns in that area in the face of their resistance culminated this week in abject surrender to become one of the last sorry acts of his leadership.

Another problem for Mr Turnbull was that his pro-market instincts (another signature policy abandoned on his prime-ministerial deathbed was large corporate tax cuts) jarred with a public mood of economic insecurity in conditions of wage stagnation and declining housing affordability.

He seemed uncertain of how to adjust to the exhaustion of the neo-liberal policy regime that has been a defining and destabilising feature of international politics since the global financial crisis.

Mr Turnbull's Labor opponent, the unpopular but underestimated Bill Shorten, proved more attuned to the electorate's anxieties by advocating redistributionist measures.

There was great optimism in the party when Malcolm Turnbull seized the leadership

Equally, Labor regularly politically outwitted Mr Turnbull. For instance, it insistently called for a royal commission into the banks.

Mr Turnbull belatedly and grudgingly agreed, only to be embarrassed by the scandalous malfeasance the inquiry uncovered.

Final twist

Mr Turnbull's prime ministership fell far short of delivering on the heady optimism of September 2015. He joins Mr Rudd, Ms Gillard and Mr Abbott in a line of unfulfilled and short-term national leaders.

Why Australia has had so many prime ministers

At the same time, and despite the capitulations, he remained a bulwark against darker nativist, populist impulses circulating within the conservative side of politics in Australia (and internationally). His fundamental instincts are cosmopolitan and progressive.

The ironic twist to this bloody story is that the conservative faction ultimately failed to have its preferred candidate replace Mr Turnbull.

Instead, the middle-ground Scott Morrison has emerged with the prime ministership.

Questions remain: will the conservatives rest with the outcome and what reckoning will voters deliver when they pass judgement on this internally racked government next year?

Paul Strangio is an associate professor of politics at Monash University and joint author of a two-volume history of the Australian prime ministership.

- Published24 August 2018

- Published24 August 2018

- Published24 August 2018

- Published23 January 2024

- Published18 May 2019