Four reasons why Australian politics is so crazy

- Published

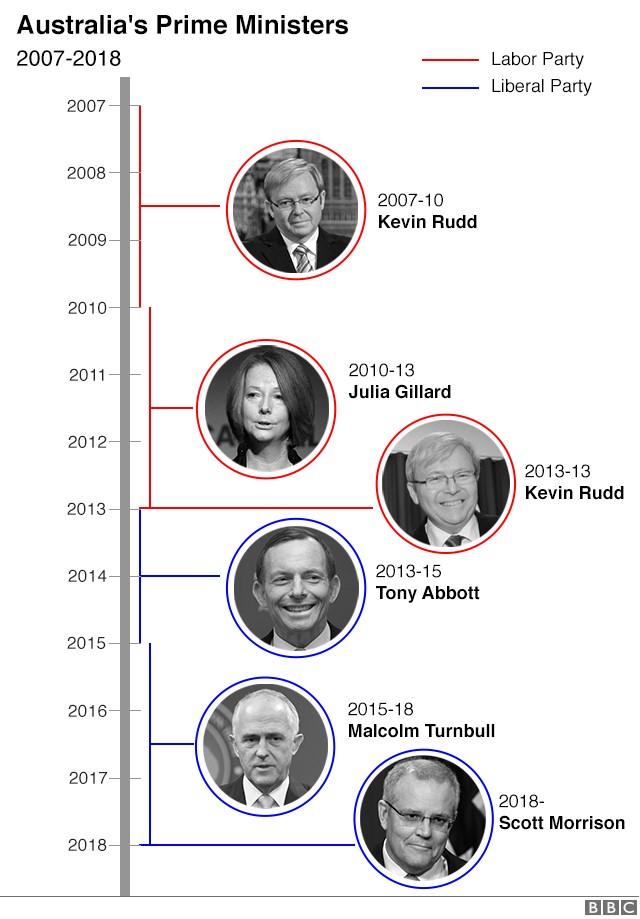

Can anyone hang on to Australia's top job?

If you can't be expected to know the name of your country's prime minister, your leaders are probably coming and going with alarming frequency.

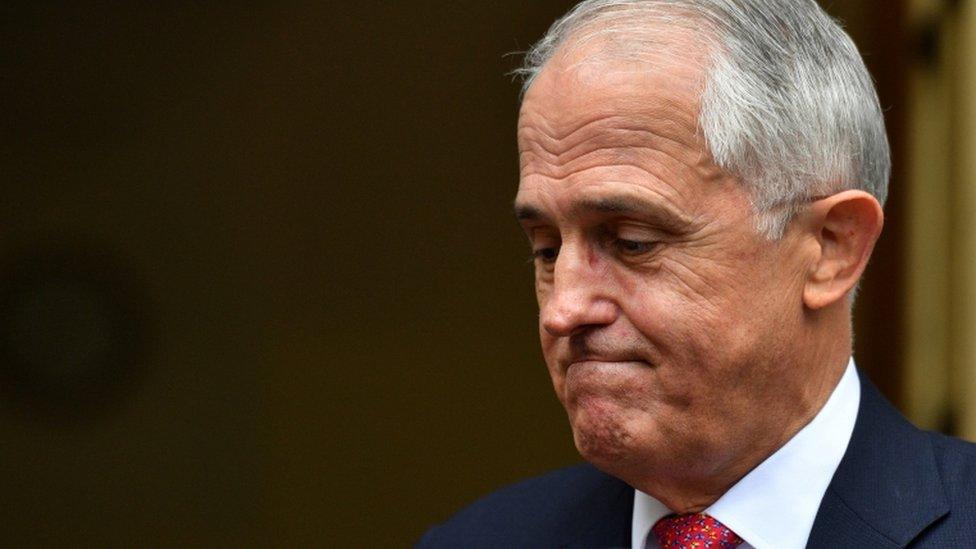

Take Australia for example - where Malcolm Turnbull has become the fourth PM in a decade to be ousted by colleagues.

The political carnage has been so extreme that in 2015 some emergency workers reportedly stopped asking patients who was prime minister, external, saying it was no longer a good indicator of their mental state.

There is even a dedicated Twitter account that documents who is in charge on a half-hourly basis.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

It wasn't always this way though. Between 1983 and 2007 Australia had just three prime ministers.

So why has Australian politics got so crazy? And does it even matter, given that the country is still considered to be one of the best places in the world to live?

1. Three-year terms

While most established and emerging democracies have four or five-year terms between elections, in Australia federal elections must be held every three years.

However, the actual length of government terms is even shorter - about 32 months on average since 1990, according to the University of Melbourne.

Advocates say this gives the electorate more control over politics.

But critics say this means that the next election is always in sight, encouraging MPs to focus more on their own short-term political survival and less on what's best for the country in the longer term.

They argue it could also increase voter apathy.

Writing in the Sydney Morning Herald newspaper, former ambassador to Israel Dave Sharma said he had served four different prime ministers, external during his four-year posting from 2013 to 2017 - Julia Gillard, Kevin Rudd, Tony Abbott and Mr Turnbull. Two of those, Ms Gillard and Mr Abbott, were removed in party coups.

Mr Sharma said it showed a "structural flaw" and called for the constitution to be changed.

"Our politicians, by proving themselves so willing to depose sitting prime ministers without reference to the electorate, have shattered a norm on which much of the stability of the Australian political system rested," he wrote.

2. Relentless news pressure

The recent spate of coups started in 2010, when Prime Minister Kevin Rudd from the Labor party was deposed by Julia Gillard (he had his revenge three years later, but lost an election just three months after that).

This first unseating coincided with an increasingly narrow focus by MPs on opinion polls, external driven by a 24-hour news cycle, Bloomberg reported.

The focus on polling has been to the detriment of other issues, which in turn has seen the two main parties lose votes to a small but growing group of minor parties and independents, who have then made it harder to pass legislation, Bloomberg said.

This time around news organisations themselves have become part of the story, with one chief political correspondent accusing a swathe of right-wing media of exhorting MPs behind the scenes to bring down Mr Turnbull. His rant went viral.

Allow YouTube content?

This article contains content provided by Google YouTube. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read Google’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Chris Uhlmann of Nine News said senior politicians had told him some news corporations were "waging a war against the prime minister" in favour of more conservative factions in the Liberal party by making private phone calls to MPs to "push them over the line".

"They are not just commentators. They are players. They have crossed the line," he said, adding: "It's the Australian country that is at stake here."

3. Mandatory voting

Australia is one of just 22 countries with mandatory voting laws, of which only half enforce them. In Australia, those who don't vote get an A$20 ($15; £11) fine.

Debate around the practice is well-rehearsed, with some critics saying it is undemocratic and others arguing that it does not equate to voter engagement.

Dr Jill Sheppard from Australian National University told Newshub in New Zealand that the law, combined with the preferential voting system, encouraged people to vote for the two main parties, external - and thus sheltered them from the potential electoral consequences of repeated coups, which are unpopular with voters.

4. 'Second-rate' leaders

In 1964 academic Donald Horne published a book that concluded: "Australia is a lucky country run mainly by second-rate people."

More Australian voters than ever might now agree with that sentiment.

Few are immune to criticism. Kevin Rudd is accused by some of pursuing revenge against Julia Gillard at the cost of unnecessary turmoil in the Labour party. Tony Abbott's policies were unpopular and his personal style was a source of ridicule.

Malcolm Turnbull has now suffered the same fate he inflicted upon Mr Abbott, described by some as a "front stabbing".

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

The new prime minister is mainstream conservative Scott Morrison. In April only 54% of Australians knew who he was, external, according to a ministerial recognition survey by the Australia Institute.

Meanwhile the main coup instigator, right-winger Peter Dutton, is being derided for failing to become PM himself. He lacked "even the organisational skills to run a chook raffle, let alone a coup", external, commentator Paula Matthewson wrote. He "couldn't organise a one-car parade", external said Malcolm Farr.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

The result is that one moderate prime minister has been replaced by another, external, leaving the right-wing insurgency unsatisfied, said Peter Hartcher in the Sydney Morning Herald.

"Of all the pointless convulsions in Australian politics in the last decade, this is surely the most pointless," he wrote.

No wonder this skit by comedy show Tonightly, urging Australia's politicians to get on with their jobs, has proved so popular. (It contains strong language, external).

- Published18 May 2019

- Published24 August 2018

- Published24 August 2018

- Published24 August 2018

- Published3 May