Why climate 'paralysis' looms over Australia's election

- Published

Scott Morrison taunted opposition MPs with a lump of coal in 2017

Two years ago, Scott Morrison stood up to address the Australian parliament while brandishing a lump of coal in his right hand.

"Don't be afraid. Don't be scared. It won't hurt you. It's coal," said Mr Morrison, who was treasurer at the time.

Little did he know then that he would be fighting the 2019 election as prime minister, and that a burning love of fossil fuels could prove fatal to his chances of keeping the job.

The political playbook, handed down from one generation to the next, tells candidates to focus on the economy if they want to win.

No doubt it will once again be vitally important to many voters in the polling booths on 18 May.

But what happens when your country's economy ticks along nicely from one year to the next, with no sign of a recession whoever is in charge?

Naturally, other things also come to the fore - like education, immigration, or in this election, the environment.

Australia election 2019: What's up for grabs?

In an ABC poll of more than 100,000 Australian voters, it's clear the environment has become the number one issue for most respondents.

Twenty-nine per cent rated it as their biggest concern, external, up from just 9% in the 2016 election.

Long-term polling by the Lowy Institute also suggests there has been a shift, external in public attitudes, with more people seeing climate change as a serious, pressing problem.

Internationally, Australians appear to care more than most about climate change, external, according to a new study published by Ipsos.

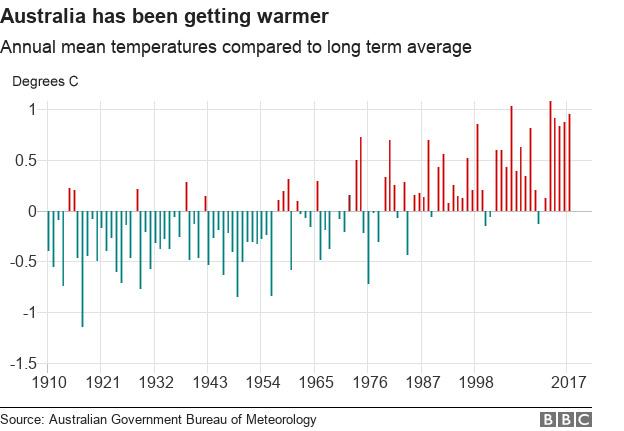

Prof David Schlosberg of Sydney University says the trend is a result of people in Australia seeing the impact of environmental change first-hand, after a summer of record temperatures and drought.

"It's not only the visibility of increasing threats to environments - fish die-offs, reef bleaching, species extinctions, bushfires," says Prof Schlosberg.

"But [it's also] the frustration with a political process and the inability to address real problems that people are experiencing."

Historically, issues like carbon taxes have caused paralysis in Australian politics.

Attempts to pass laws to tax high-polluting companies were a large reason for a fall in public support for the Labor government and the ousting of then Prime Minister Kevin Rudd in 2010.

Up to a million fish have perished in New South Wales river systems, authorities say

Despite huge protests the tax became law under his successor, Julia Gillard. But when the Liberal-led coalition came to power in 2013 it set about repealing the law.

The coalition has torn itself to shreds over the issues of energy and emissions targets in the past year, ditching former Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull because of party divisions.

Urban-rural divide

In the current election, the political rhetoric on climate seems to depend largely on where the party leader finds themselves and the particular concerns of those local economies.

In the ABC poll of issues most important to voters, the economy was a close runner up at 23%.

16.3mregistered voters

151MP seats up for election

40Senate seats (of 76 in total)

1.6m sq kmsize of Durack, the largest constituency

A$20Penalty for not voting

So speeches delivered in metropolitan Melbourne, for instance, often talk about the future of hydro energy and other renewables.

But on the stump in rural Queensland or New South Wales, support can switch back sharply where many jobs are dependent on mining.

Labor leader Bill Shorten has struggled to convince some with his nuanced position on supporting the giant new Adani coal mine, planned for Carmichael, Queensland.

The Adani mine has faced huge opposition from those concerned about its environmental impact

Mr Shorten has refused to rule out conducting an environmental review - demanded by many within his own party - if he becomes prime minister.

The mine may now be less of an election issue than first thought. The Queensland government has put construction work on hold indefinitely, thanks to concerns about the impact on the black-throated finch, an endangered bird found in the area.

But there is no shortage of debate on Australia's domestic and international climate responsibilities.

Part of the public frustration seems to be in pinning down exactly what the politicians believe.

Even some politicians who have held apparently definitive positions on climate change have been sending mixed messages.

For those reliant on the mining industry talk of cutting production is alarming

Former Prime Minister Tony Abbott, who once described climate science as "absolute crap" and steered the ditching of the carbon tax, recently reversed his opposition to Australia fulfilling its Paris Agreement obligations.

His decision may have something to do with the polls which suggest he could lose his electorate to an independent candidate who wants to cut Australia's carbon emissions.

According to Prof Schlosberg, the main parties have found themselves far behind the curve on climate change.

"Australia faces some very real impacts, and they are now - rather than only in the distant future," he says. "Yet neither major party has a comprehensive plan for adaptation."

The challenge for the country's politicians before 18 May is to convince voters they really do care as much about saving the planet as they do about winning office.

- Published24 April 2019