Fadak Alfayadh: The refugee who wants to meet you

- Published

Fadak Alfayadh wants to change the narrative around refugees

"My story is the most powerful tool that I have," says Fadak Alfayadh.

As a child, Fadak fled conflict-torn Iraq in the middle of the night with her mother and two sisters - a tense journey that would lead them to a new life in Australia.

In Melbourne they built a strong connection to the local community, but it wasn't long before Fadak started to doubt how welcome she really was.

"It happened bit by bit," says Fadak, now 26, of what she saw as refugees being increasingly "scapegoated" in Australia.

But it also made her wonder: what if people could meet her and hear her story? Would their attitudes change?

Fadak's memories of her childhood are of the aroma of her grandmother's sweet bread and a dusty, cousins-wide kickball game in Baghdad. But amid rising tensions in Iraq, Fadak's mother piled her daughters into a car with the headlights off and made for Jordan.

Fadak left Baghdad as a young child and migrated to Australia

After a long drive and a short stay in Jordan, they soon joined Fadak's father, Jalal, at his home in Australia. A surgeon, Jalal had fled Baghdad in the late '90s after being conscripted to serve in Saddam Hussein's oppressive regime.

"Back then [in 2003], if you were a refugee you could bring your family to Australia to be together with you," Fadak explains. "Whereas, nowadays, an asylum seeker is... unable to do so," she adds, referring to tough policies enacted by Australia to deter migrant journeys.

Six months after the family was reunited, Jalal was killed in a car accident. Slowly Fadak realised she was not returning home to sweet bread and dusty kickball. She jumped at the sound of thunder because it reminded her of a bomb, and struggled to find the English words to express her war-torn experiences. Later, she felt an increasing sense of unease about her place in Australia.

"In retrospect, when [former Prime Minister] John Howard used the story of 'boat people' to twist the narrative about migrants, refugees and diverse people in general, I began to see how we were being used as scapegoats," she says.

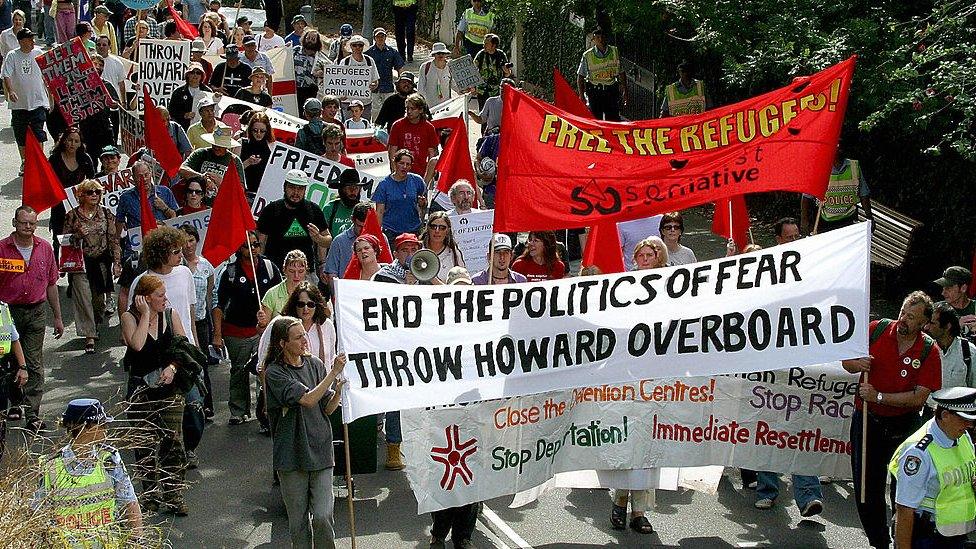

In 2001, allegations were made public that asylum seekers travelling to Australia had thrown children into the sea in an apparent ploy to attract a rescue effort.

The "children overboard affair'', as it was dubbed, led to stricter border protection measures which drew support from the shocked Australian public.

But a government inquiry later found no evidence that children had been thrown overboard - and that Mr Howard's government had known this to be the case. A previous prime minister, Bob Hawke, called it "the most despicable of lies".

People protest in Sydney over the "children overboard" affair

In the years that followed, Fadak says she felt the national mood darken towards refugees.

"The distinction between the everyday community and the general public discourse is the challenge, then and now," she says. Fadak laments the issues refugees still face in Australia today, 18 years later.

Since 2013, Australia has sent all asylum seekers arriving by boat to the Pacific islands of Manus Island (Papua New Guinea) and Nauru for processing. It insists tough policies such as this save lives at sea and prevent human trafficking, but critics say the programme is "brutal" and "inhumane". Last year, the UN called on Australia to immediately evacuate asylum seekers from the islands to prevent an unfolding health crisis.

Fadak says her experiences have compelled her to help "change the world". After studying law and politics, she began advocating for migrants in a community legal centre. Later, she expanded her efforts through public speaking, commentary in the media, and on social media.

It was from this that "Meet Fadak" was conceptualised - a national speaking tour where Fadak gives talks, meets Australians and breaks down walls.

Fadak raised money for the national speaking tour with the help of a government-backed refugee organisation, Road to Refuge. Her launch event sold out, and she has since travelled around Australia, reaching hundreds of thousands of people.

"I thought if people were able to meet me and hear me out, they would find their negative connotation towards refugees shift," she says.

Australia resettled 12,706 refugees in 2018, ranking behind only Canada and the US. But the number of refugees living temporarily in Australia stands at 56,933 - which is 45th globally, according to most recent UN statistics.

Fadak's advocacy has taken her around Australia and internationally, including to Geneva

Fadak says she faced a backlash to her mission from early on; some people on social media, for instance, told her that Australia "didn't want Muslims". But she is also inspired by meeting people from all walks of life.

"Now I sit down with former refugees from all over the world," she says. "I also sit down with people who want to know how they can help, people who are hopeful, people who are angry, and people who have never engaged with the topic before." She adds that some had told her they related to her story even without being refugees.

Fadak has delivered her own TEDx talk and was recently was one of two refugee representatives invited to attend the annual UN NGO consultations in Geneva. "My hope is to change the narrative for refugees and asylum seekers. We've 'dehumanised' refugees, but the fact is there are many more things that connect us than divide us. It's a story worth telling."

Naomi Steer, from Australia for UNHCR, the UN's refugee agency agrees: "Fadak's spot on about the power of stories - they're how we connect as humans when everything else is stripped away. Our work to address record high levels of global displacement is a huge challenge, which is why inspiring grassroots work and stories from people like Fadak are so important."

She adds that supporting refugee women and children - who comprise 80% of refugees worldwide - remains an important focus.

How a refugee wrote a book by text message

Fadak says big change can start with simply having a conversation with a refugee.

"A considerable amount of hate and fear towards refugees exists in our community and we need to tackle it at the core," she says. "It is everyone's responsibility to stand up to that fear."