Dissociative Identity Disorder: The woman who created 2,500 personalities to survive

- Published

Jeni Haynes was allowed to let six of her personalities testify against her father

There was only one woman in the witness stand that day but out of her came six people prepared to testify about the extreme abuse she had suffered.

"I walked into court, I sat down, I made the oath, and then a few hours later I got back into my body and walked out," Jeni Haynes told the BBC.

As a child, Jeni was repeatedly raped and tortured by her father, Richard Haynes, in what Australian police say is one of the worst child abuse cases in the country.

To cope with the horror, her mind used an extraordinary tactic - creating new identities for her to detach from the pain. The abuse was so extreme and so persistent, she says she ultimately generated 2,500 distinct personalities to survive.

And in the landmark trial in March, Jeni confronted her father to present evidence against him through her personalities, including a four-year-old girl named Symphony.

It's believed to be the first case in Australia, and perhaps the world, where a victim with diagnosed Multiple Personality Disorder (MPD) - or Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID) - has testified in their other personalities and secured a conviction.

"We weren't scared. We had waited such a long time to tell everyone exactly what he did to us and now he couldn't shut us up," she said.

On 6 September Richard Haynes, now 74, was sentenced to 45 years in jail by a Sydney court.

Warning: Contains descriptions of violence and child abuse

'I wasn't safe in my own head'

The Haynes family moved from Bexleyheath in London to Australia in 1974. Jeni was four years old, but her father had already begun his abuse, and in Sydney this escalated into sadistic, near-daily violations.

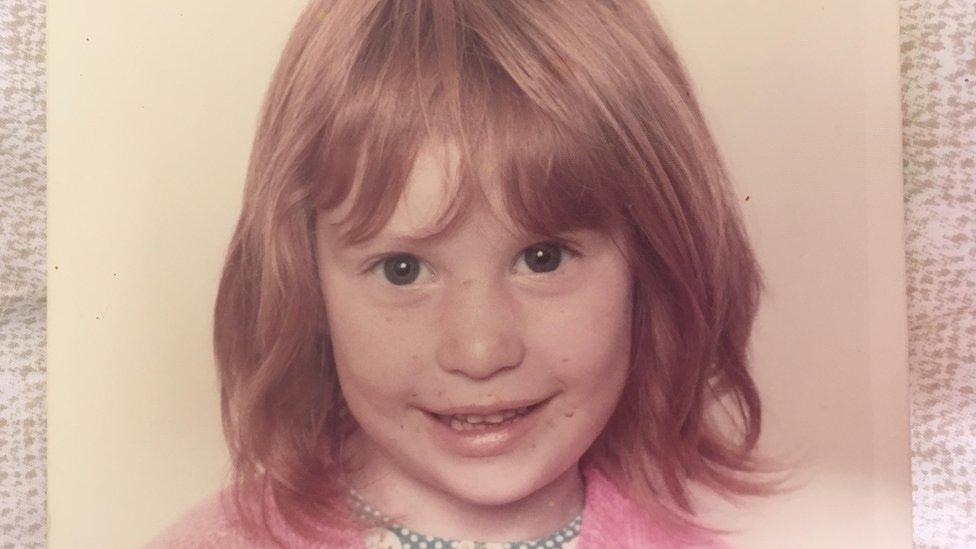

Jeni's multiple personalities were her way to hide her real self from the abuse

"My dad's abuse was calculated and it was planned. It was deliberate and he enjoyed every minute of it," Jeni told the court in a victim impact statement in May. She waived her anonymity rights, as a victim of abuse, so her father could be identified.

"He heard me beg him to stop, he heard me cry, he saw the pain and terror he was inflicting upon me, he saw the blood and the physical damage he caused. And the next day he chose to do it all again."

Haynes also brainwashed his daughter into thinking he could read her mind, she said. He threatened to kill her mother, brother and sister if she even thought about the abuse, let alone told them.

"My inner life was invaded by Dad. I couldn't even feel safe in my own head," Jeni said. "I could no longer examine what was happening to me and draw my own conclusions."

She composed her thoughts through song lyrics, to try to hide them:

"He ain't heavy/he's my brother" - when worrying about her siblings.

"Do you really want to hurt me/ Do you really want to make me cry" - when thinking about her ordeal.

Her father restricted her social activities at school to minimise other adult oversight. Jeni learnt to keep herself small and silent, because if she were to be "seen" - such as when her swimming coach approached her father to encourage her natural talent - she would be punished.

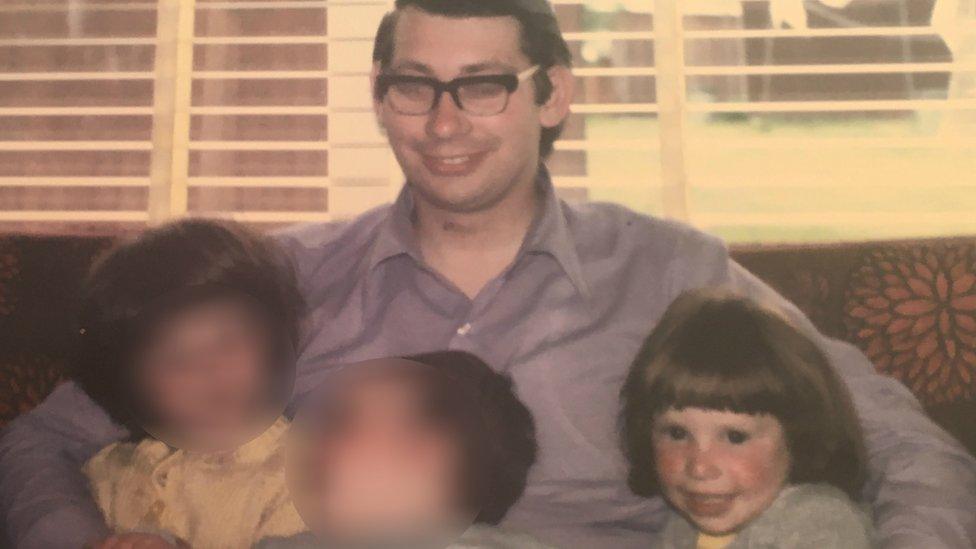

Richard Haynes pictured with his three children - Jeni is on the right

Jeni was also denied medical care for her injuries from beatings and sexual abuse, which have developed into serious lifelong conditions.

Now aged 49, Jeni has irreparable damage to her eyesight, jaw, bowel, anus and coccyx. These have required extensive surgeries including a colostomy operation in 2011.

The abuse would continue until Jeni was 11, when the family moved back to the UK. Her parents divorced shortly after, in 1984. She believes no-one, not even her mother, was aware of what she was going through.

'He was actually abusing Symphony'

Contemporary Australian experts refer to Jeni's condition as Dissociative Identity Disorder, and say it is heavily linked to experiences of extreme abuse against a child in what is supposed to be a safe environment.

"DID really is a survival strategy," Dr Pam Stavropoulos, a childhood trauma expert, told the BBC.

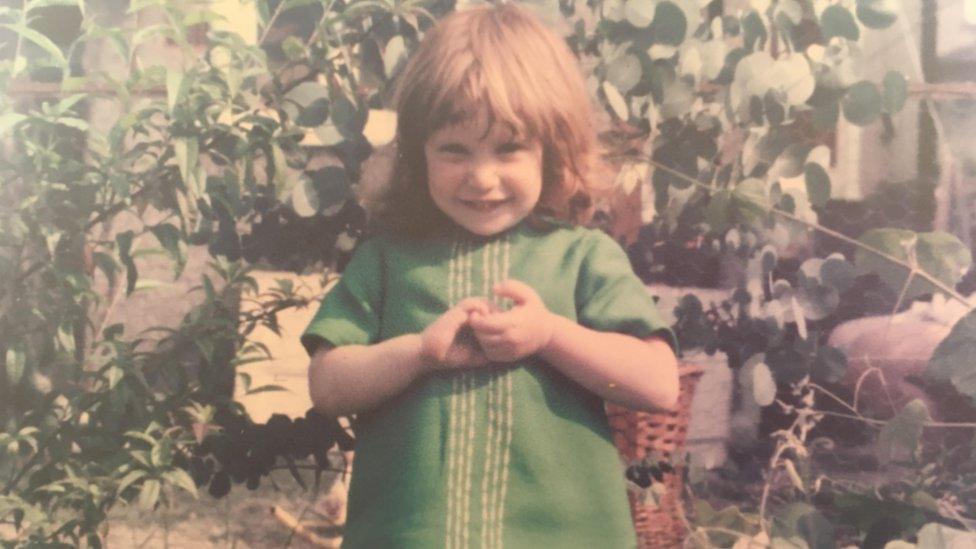

Jeni says she was Symphony for most of her early childhood

"It serves as a very sophisticated coping strategy that is widely regarded as extreme. But you have to remember, it's the response to extreme abuse and trauma the child has undergone."

The earlier the trauma and the more extreme the abuse, the more likely it is that a child has to rely on disassociation to cope, leading to these "multiple self-states".

The first personality Jeni says she developed was Symphony, the four-year-old girl who, she says, exists in her own time reality.

"She suffered every minute of Dad's abuse and when he abused me, his daughter Jeni, he was actually abusing Symphony," Jeni told the BBC.

As the years went on, Symphony created other personalities herself to endure the abuse. Each one of what would be hundreds and hundreds of personalities had a particular role in containing an element of the abuse, whether it was a particularly horrifying assault, or a triggering sight and smell.

"An alter would walk out the back of Symphony's head and take on the distraction," Jeni told the BBC.

"My alters have been my defences against my father."

It's while discussing this that Symphony presents, about half an hour into our conversation. Jeni has warned this might happen, and there is a sign when it does - she struggles to articulate an answer before transitioning.

"Hello, I'm Symphony. Jeni's gotten into a pickle, I'll come tell you all about this if you don't mind," she says in a rapid burst.

Symphony's voice is higher, her tone brighter, more girlish and breathless. We talk for 15 minutes and her microscopic recollection of decades-old events around "Daddy's nastiness" is astounding.

"What I did was I took everything I thought was precious about me, everything important and lovely and hid it from Daddy so that when he abused me he wasn't abusing a thinking human being," Symphony said.

Some of the 'people' Jeni says helped her survive

Illustration of Jeni Haynes with her multiple personalities

Muscles - a teenager styled like Billy Idol. He is tall and wears clothes which show off his strong arms. He's calm and protective.

Volcano is very tall and strong, and clad from top to toe in black leather. He has bleached blond hair.

Ricky is only eight but wears an old grey suit. His hair is short and bright red.

Judas is short with red hair. He wears plain grey school trousers and a bright green jumper. He always looks like he's about to speak.

Linda/Maggot is tall and slender, wearing a 1950s skirt with pink poodle appliqués. Her hair is in an elegant bun and she has tapered eyebrows.

Rick wears huge glasses - the same sort Richard Haynes used to wear. They dwarf his face.

In March, Jeni was allowed to testify in court as Symphony and five other personalities, each of which would have shared different aspects of the abuse. The trial was heard by a judge only, because lawyers considered the case to be too traumatising for a jury.

Haynes initially faced 367 charges, among them multiple counts of rape, buggery, indecent assault and carnal knowledge of a child under 10. Jeni, in her personalities, would have been able to provide detailed evidence on every single offence in court. The separate identities have helped her to preserve memories that might otherwise have been lost to trauma.

Prosecutors had also lined up a range of psychologists and experts in DID, to give evidence about the condition and reliability of what Jeni would say.

"My memories as a person with MPD are as pristine today as they were the day they were formed," she told the BBC, before switching briefly to the plural. "Our memories are just frozen in time - if I need them, I just go and pick them up."

Symphony had intended to relive "in excruciating detail" the particulars of the crimes over the seven years in Australia. Muscles, a burly 18-year-old strongman, would have given evidence of physical abuse while Linda, an elegant young woman, would have testified on the impact on Jeni's schooling and relationships.

The Haynes' family home in Greenacre, in western Sydney

Symphony "was hoping to use the testifying to grow up too", says Jeni. "But we only got through 1974 before he rolled over and showed his belly. He couldn't deal with it."

About two and half hours into Symphony's testimony on the second day of the trial, her father changed his plea to guilty on 25 charges - "the worst ones"- says Jeni. Dozens more were counted towards his sentencing.

'MPD saved my soul'

"It's a landmark case because, as far as we're aware, it's the first time in which the testimony of different parts of person with DID has been taken at face value into the court system and has led to a conviction," says Dr Cathy Kezelman, the president of Blue Knot Foundation, an Australian organisation helping survivors of childhood trauma.

Richard Haynes pleaded guilty to more than two dozen child sexual abuse charges

Jeni first reported the abuse in 2009. It has taken 10 years for the police investigation to culminate in Richard Hayne's conviction and jailing.

He was extradited from Darlington in north-east England in 2017, where he had served a seven-year sentence for another crime. He had been living among Jeni's extended family, to whom he cast his daughter as a liar and manipulator.

Since learning of the abuse, Jeni's mother - who divorced Haynes in 1984 - has become her strongest supporter in her pursuit of justice.

But for decades, Jeni had struggled to receive help for her trauma. She says counsellors and therapists turned her away because her story sparked disbelief, or was so traumatic they could not deal with it.

Dissociative Identity Disorder

Disassociating - disconnecting from yourself or the world - is considered a normal response to trauma.

But DID can be triggered if a person, particularly a child, has to survive complex trauma over a long time.

Having no adult support - or an adult who says the trauma was not real - can contribute to developing DID.

A person with DID may feel they have multiple selves who think, act or speak differently, or even have conflicting memories and experiences.

There is no specific drug treatment - specialists will mostly use talking therapies to help DID patients.

Despite being a widely accepted and evidence-backed diagnosis these days, DID commonly raises doubt among the general population and even some medical circles.

"The nature of the condition is such that it does generate disbelief, incredulity, and discomfort about the causes of it - partly because people find it hard to believe that children can be subjected to such extreme abuse," Dr Stavropoulos said.

"That's why Jeni's case is so important because it's bringing wider awareness of this very challenging but not uncommon condition that still isn't sufficiently realised."

Jeni says her MPD saved her life and saved her soul. But the same condition, and her underlying trauma, have also resulted in great hardship.

Several of Jeni's personalities are highly intelligent and sophisticated adults

She has spent her life studying, getting a masters and PhD in legal studies and philosophy but she has struggled to manage full-time work. She lives with her mother, both of them reliant on their welfare pensions to get by.

In Jeni's victim impact statement, she said she and her personalities "spend our lives being wary, constantly on guard. We have to hide our multiplicity and strive for a consistency in behaviour, attitude, conversation and beliefs which is often impossible. Having 2,500 different voices, opinions and attitudes is extremely hard to manage".

"I should not have to live like this. Make no mistake, my dad caused my Multiple Personality Disorder."

Jeni sat metres away from her father in court on 6 September to see him sentenced to 45 years. Haynes, who is suffering from poor health, will serve at least 33 years before he is eligible for parole.

Sentencing Judge Sarah Huggett said he would likely die in jail. His crimes were "profoundly disturbing and perverted" and "completely abhorrent and appalling", she said.

Judge Huggett said it was "impossible" for the sentence to reflect the gravity of the harm.

"I passionately want my story told," Jeni told the BBC before the sentencing. "I want my 10-year struggle for justice to literally have been the fire that ripped through the field so that people behind me have a much easier road.

"If you have MPD as a result of abuse, justice is now possible. You can go to the police and tell and be believed. Your diagnosis is no longer a barrier to justice."

You might also be interested in:

If you have been affected by sexual abuse or violence, UK-based help and support is available at BBC Action Line. In Australia you can contact Kids Helpline, external, Lifeline, external or Blue Knot Foundation, external.

- Published22 October 2018

- Published27 August 2019