Australia bushfires: Which animals typically fare best and worst?

- Published

A badly burnt koala in care at a koala hospital in New South Wales

Koalas yelping for help, beehives caught in the path of danger, food chains interrupted: Australia's bushfire crisis is having a destructive effect on the nation's wildlife, writes Gary Nunn in Sydney.

The deadly spring blazes have burnt through almost two million hectares in New South Wales and Queensland alone. Many animals are resilient but others, unfortunately, don't survive, often because their potential escape habitats have already been destroyed by human activity.

The animals more likely to perish in bushfires

Koalas are typically slow-moving and their normal danger-avoidance strategy - curling into a ball atop a tree - has left them trapped in extreme fires. For anyone within earshot, there's one clear indicator that an animal is in trouble.

"Koalas don't make noise much of the time," says Prof Chris Dickman, an ecology expert at Sydney University.

"Males only make booming noises during mating season. Other than that they're quiet animals. So hearing their yelps is a pretty bad sign things are going catastrophically wrong for these animals."

A woman rushed into the bush to rescue a koala crying out for help

In fact most forest animals, with a few notable exceptions, aren't vocal, making these sounds - as seen in the upsetting video above which has been shared widely - all the more alarming.

"These screams aren't part of the vocal repertoire of the forest," Prof Dickman adds. "They only happen during times of great stress or pain - such as when a possum is savaged by a dog."

In the aftermath of a blaze, frogs and skinks (lizards) are among animals left vulnerable, says wildlife ecologist Prof Euan Ritchie from Deakin University.

"The fire can kill their food or shelter, or both. These animals might survive the immediate effects of a fire if they can escape in time, but if it burns their habitat, they're more exposed to the introduced predators," he says.

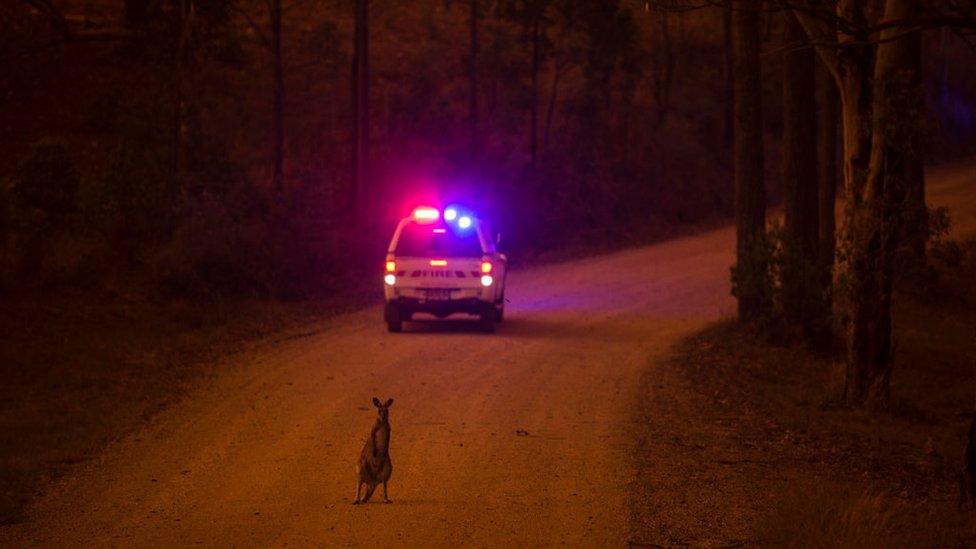

A wallaby on the road behind an emergency car after escaping a bushfire near Nana Glen in New South Wales

Disconnected patches of habitat left as a result of bushfires and human clearing also pose a threat to already endangered species.

These include the western ground parrot, the Leadbeater's possum, the Mallee emu-wren (a bird which can't fly very far), and Gilbert's potoroo - Australia's most endangered marsupial. Beekeepers have also told of losing hives in fire-hit forests.

Prof Dickman says it's "naive" to say that, because fires have always burned in Australia, there's historical resilience.

"It's a very different landscape now to before the Europeans arrived," he tells the BBC.

Most animals will try to flee a fire - but they need somewhere to go

"Koalas are much less resilient now simply because we've chopped up the habitats where they occur - leaving them isolated with no place to crawl back to once the fires die down."

Prof Ritchie agrees: "Lots of Aussie landscape has been quite used to fire for tens of thousands of years - but not at this frequency or severity".

The survivalists and opportunists

The most resilient animals are those that can burrow or fly. Possums may get singed, but can be protected in tree hollows. Wombats can sit out a fire in their deep burrows. Snakes also tend to go underground for protection.

Kangaroos and wallabies can move quickly to flee fires, though sometimes they can be trapped, external or face other difficulties.

Injured animals might take a long time to recover from burns

Tree goannas can protect themselves underground before emerging to hunt for injured prey

Goannas - large carnivorous reptiles - can actually benefit from bushfires.

"In central Australia we've seen goannas coming out from their burrows after a fire and picking off injured animals - singed birds, young birds, small mammals, surface dwelling lizards and snakes," says Prof Dickman.

But the animals most concerning for ecologists are introduced species: mainly red foxes and feral cats. These non-native predators are thriving from the bushfires.

A lucky possum might be able to ride out a bushfire inside a tree hollow

The cats are the bigger worry: red foxes take bait designed to control them, but cats often don't.

"They have the same strategies as the birds of prey - turning up at the aftermath and picking out injured animals" Prof Dickman says. "Cats can move 20km [12 miles] from an unburnt area to the edge of a fire - it opens up the ground for hunting."

Black kites, whistling kites and brown falcons have even been spotted picking up burning twigs, flying to areas of unburned grass and dropping them to start new fires there. This exposes their prey attempting to flee the blazes: small mammals, birds, lizards and insects.

A black kite hunting on the outskirts of a bushfire

"This behaviour helps them find small reptiles to eat more easily," says Prof Ritchie. "You could hypothesise they create these fires for their own advantage."

This hypothesis is backed up by a study of witness accounts, external undertaken by Bob Gosford, an ornithologist in the Northern Territory, who led the documentation of 20 witness accounts taken over six years.

What's the long-term impact?

Animal rescues make for great headlines, and treatment centres have a positive effect in areas such as western New South Wales and south-east Queensland, where koala are in decline.

Koala Corduroy Paul was able to be saved from the fires

But, Prof Ritchie says, it's unclear how - outside of those areas - saving one animal would affect the population as a whole.

"Every animal matters, and the public forms a deep connection with these animals and want to help them in terrible times like when they're caught in fires," he says.

But experts say it is these things that will mitigate the risk to wildlife: maintaining large areas of connected habitat; undertaking controlled burns (where fires are lit in safe conditions to reduce fuel loads); managing introduced predators; and action on climate change.

Many habitats which have been burnt may take a long time to recover, and the fires raging across several states now pose an ongoing threat.

"We're seeing really big fires, really hot fires and fires occurring at times of year wildlife aren't used to. If it's business as usual on lack of climate change action, we'll see that threat move to severe pretty quickly."

- Published3 November 2019

- Published20 November 2019

- Published30 October 2019

- Published21 November 2019

- Published14 November 2019

- Published13 November 2019

- Published12 November 2019