Australia fires: 'Apocalypse' comes to Kangaroo Island

- Published

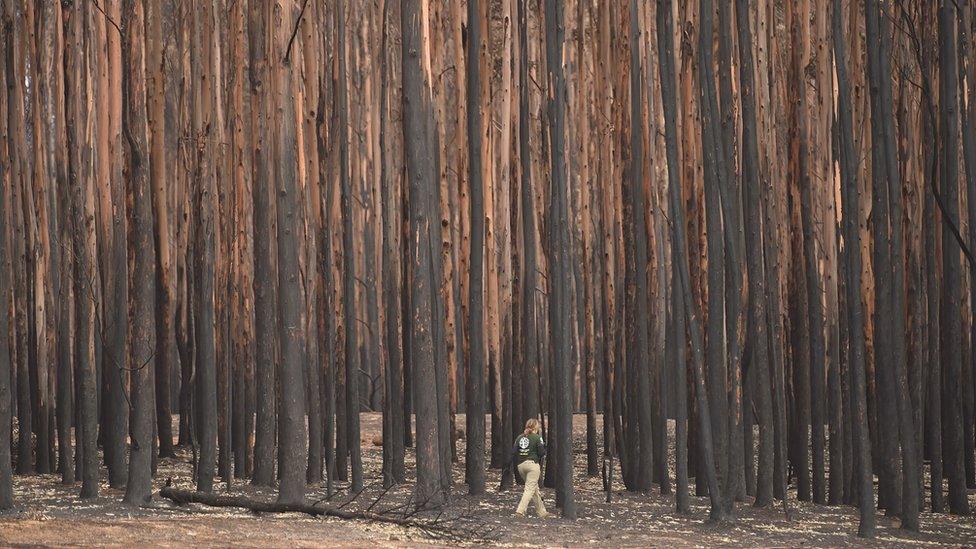

Rescuers have scoured fire-ravaged Kangaroo Island for surviving wildlife

Kangaroo Island in South Australia has been likened to a Noah's Ark for its unique ecology. But after fierce bushfires tore through the island this week, there are fears it may never fully recover.

"You see the glowing in the distance," says Sam Mitchell, remembering the fire that threatened his home, family, and animals last week.

"The wind is quite fast, the glowing gets brighter - and then you start to see the flames."

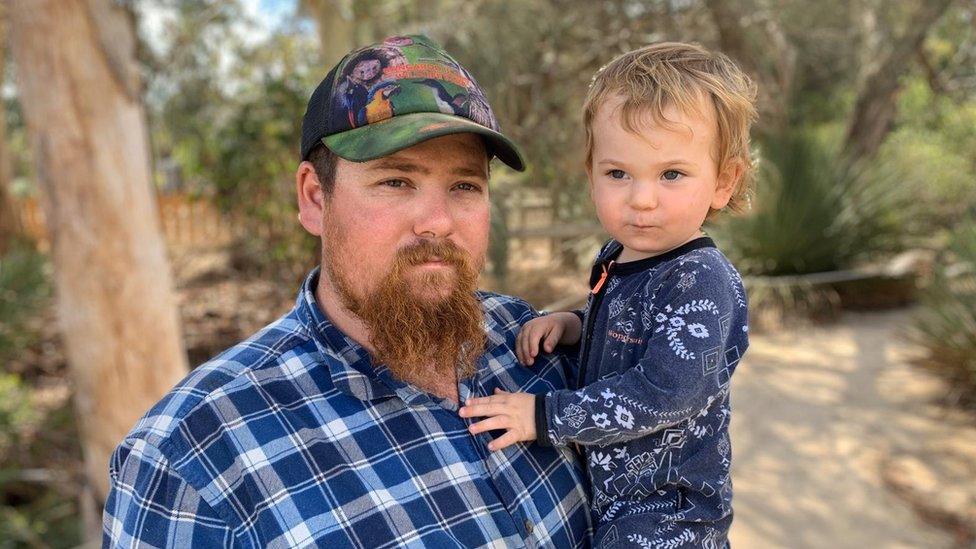

Sam runs Kangaroo Island Wildlife Park and lives there with his wife and 19-month-old son, Connor. As the flames approached, an evacuation warning was issued. Within 20 minutes, "everyone was gone".

But Sam - and four others - stayed behind.

"You can't move 800 animals including water buffaloes, ostriches and cassowaries [an ostrich-like bird]," he says.

Sam Mitchell and his family stayed behind to protect his animals

"We decided that if we can't move them we'll see if we can save them. We had the army helping us. Somehow, we were spared. It burnt right around us."

The fire, on 9 January, was the second major blaze to ravage Kangaroo Island in less than a week. Two men had died in a blaze on 4 January. Authorities believe they were overrun by flames as they drove along the highway.

The fires on Kangaroo Island have been shocking for their speed and extreme behaviour.

After his park was spared, Sam soon realised that the eastern town of Kingscote - where he'd sent his son - was under threat.

"I thought I was sending him to safety," he says. "It turns out the fire missed us and was heading in their direction."

The fire came dangerously close to Kingscote but did not impact the town. While talking to me, Sam keeps a close eye on his son, who's now back in the park.

The towering fire as seen from the air on 9 January

"It's so hard to see him playing innocently when there are fires all around us," he says.

Inescapable trail of destruction

Driving through the fire trail in Kangaroo Island, there are rows upon rows of blackened trees, some still burning from inside. The scorched earth smoulders and smoke fills the air.

At least a dozen charred koala and kangaroo carcasses lie on the side of the road. You cannot escape the death and destruction.

It's an ecological disaster so big, the army have been called in. Some have helped dig trenches to bury the thousands of sheep and cattle killed.

Many animals on the island died in the fires

The army has helped dig trenches to bury animal carcasses

At Hanson Bay in the island's west, we watch Australian and New Zealand soldiers fan out across paddocks, collecting the remains of hundreds of koalas, kangaroos, wallabies and birds.

With masks to help keep out the stench, they silently move the charred carcasses into piles - which are then transferred to a hire truck and offloaded by hand into a deep trench.

"It's not a fun task," admits Major Anthony Purdy, who oversees the grim mission. "Nobody likes to handle deceased wildlife, but we'll be here to support the community and will be for as long as we are wanted and needed."

'The landscape was so important'

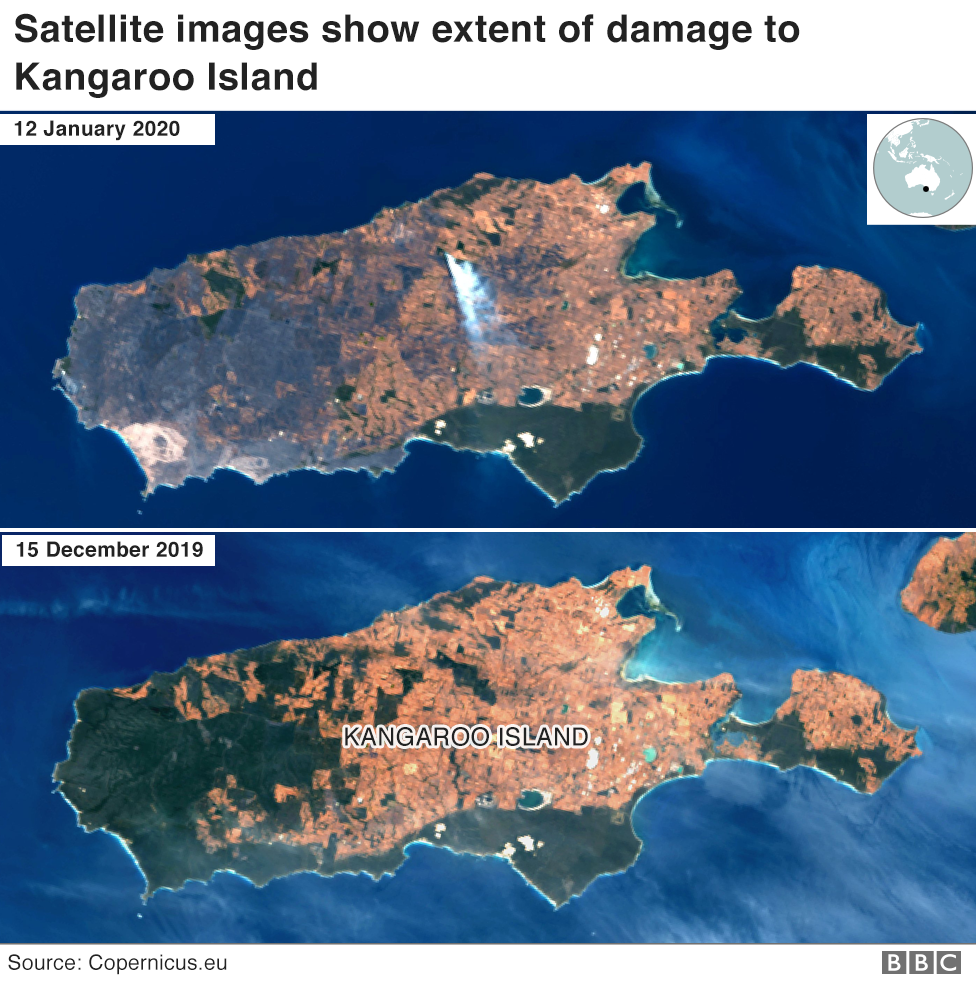

Kangaroo Island is one of Australia's most important wildlife sanctuaries, renowned for its biodiversity. Now it's feared that half of the island (more than 215,000 hectares) has been scorched.

In some parts of Vivonne Bay, the fires burned right up to the sea.

"It's apocalyptic," says Caroline Paterson, a former ranger who was based in Flinders Chase for eight years.

The south-western area is home to the island's national park. Now the whole has been ravaged by fires that have burned since 20 December.

"We're struggling to look for remnants of intact vegetation where some species may still be present," says Caroline, tearfully.

"It's a very special place. The island has been protected from a lot of diseases. The whole landscape was so important."

Ancient habitats

One of the reasons Kangaroo Island retained a good number of its original species was because rabbits and foxes weren't introduced there.

This, says Christopher Dickman, a professor of ecology at the University of Sydney, meant the native wildlife was spared fox predation, and the vegetation was not at risk from rabbits - unlike the mainland.

"It's the third largest island off the coast of Australia, and it was separated from mainland Australia many thousands of years ago," says Prof Dickman.

"A lot of the flora and fauna there are distinctive because a lot of the island's habitats remained fairly pristine. It's like stepping back in time when you cross to Kangaroo Island.

Much of the Flinders Chase National Park has been scorched

There are fears for the endangered Kangaroo Island dunnart

"The western parts have remained more or less intact so you can get a sense of what southern Australia was like. It's like a southern Australian ark, retaining a really good complement of its species."

But scientists are now worried about many endangered species - including the Kangaroo Island dunnart, a mouse-like marsupial, and the glossy black-cockatoo.

The island is also home to a pure strain of Ligurian bees, originally from Italy. Nearly a quarter of the beehives are believed to have been lost in the bushfires.

There's also concern for the pygmy possums and the southern brown bandicoot on the island.

"They are likely to have perished in the flames and for those who've survived, their habitats are gone," says Prof Dickman.

"There's a risk of lack of food, water and shelter. Also, the presence of feral cats - which have been a problem before the fires. They're likely to be at risk of cat predation."

Both residents and scientists are trying to fathom the scale of the damage. But it's proving difficult because fires are still active in some areas - and other parts of the island are deemed too dangerous.

Fires swept through Kangaroo Island at frightening speed

The fires burnt right up to the sea's edge

"At the moment the fires are still going and the parks are closed," says Caroline Paterson.

"We have no way of knowing exactly what has been lost. [But] if you don't have habitat, you don't have species."

The race to save koalas

It's estimated that half of the Kangaroo Island's 50,000 koalas have perished in the fires - a huge loss for a population that was thriving here.

Unlike other parts of Australia, the koala population on Kangaroo Island is free of chlamydia. It's a disease which frequently leads to blindness, severe bladder inflammation, infertility and death among the animals.

Since the fires started, Sam Mitchell has received koalas with severe burns almost on a daily basis. Even on the night when the bushfire was coming at them, two dozen koalas were brought in for treatment.

The fire devastated the prized local koala population

A section of the outside grounds has been turned into a makeshift clinic. Volunteers race to treat as many animals as possible.

Duncan McFetridge, a retired vet, and Belinda Battersby, a veterinarian nurse, are scraping some dead skin off one koala's burned hand.

The koala has been sedated but is seems in pain - twitching as they apply antibiotics and wrap its limbs. But not all those brought in can be saved. Many are too badly injured.

"Many will be euthanised unfortunately," says Duncan.

"Some are too far gone. You do what you can and you make sure you don't end up causing more distress to the animal. [We want] to get them back to where they want to be - and that's back in the trees."

Some animals have been put in laundry baskets as there's nowhere else to keep them. The whole park is running on generators because the fires have destroyed power lines in the area.

It's a difficult place to treat so many badly-injured animals.

"We have to contend with the wind which brings dust and contaminates wounds," says Belinda. "We also need caging. We need better cages for their food and for recovery later."

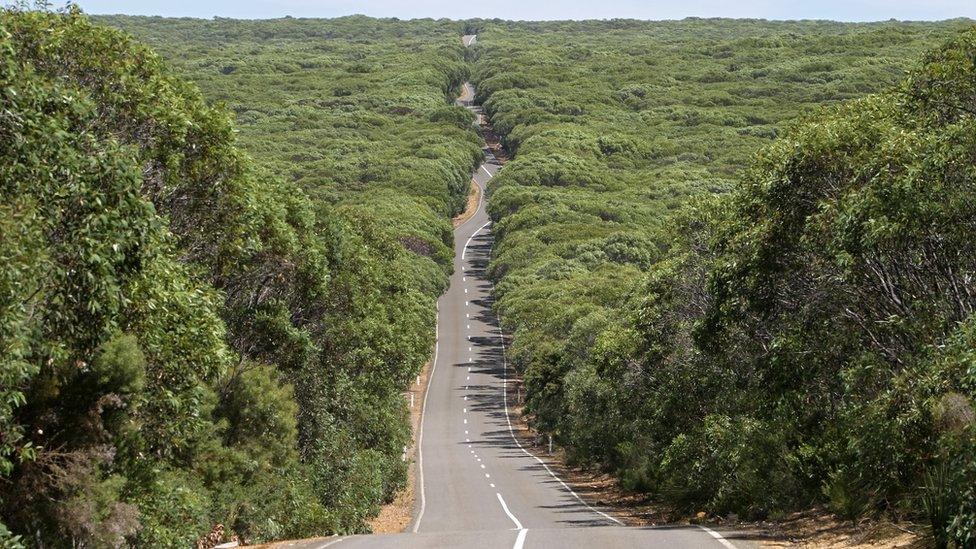

A famous long, winding road runs through Flinders Chase National Park on the island

The same road after fires this month

Every sector of this island has been hit hard by the fires - including agriculture. Tens of thousands of sheep and cattle were burned and thousands of acres of pasture were scorched.

"Sometimes I wake up and I think business is as normal," says Sam. "And then reality hits and (I know) it won't be the same way for a long time."

This was supposed to be a busy season at his wildlife park, but all the tourists have been evacuated. It's a difficult time for him and his family.

The BBC spoke to run participants on Kangaroo Island who said it was a good way to deal with the stress of the fires.

"We're a private business - myself, my wife, my son - and I have ten staff relying on me. The animals and the wildlife are what brings people here.

"We should be seeing between 100 to 200 people a day, which is what funds the park but that's all shut down now. We could go broke pretty quickly."

And, says Sam, the worst may not be over.

"There are a few patches that haven't burned," he says. "There are fires still going. We've got some hot days coming and summer is not over - so we could potentially see the rest of the island go."

Additional reporting by Simon Atkinson

- Published14 January 2020

- Published7 January 2020

- Published17 November 2019

- Published9 January 2020

- Published2 January 2020

- Published24 December 2019

- Published4 January 2020

- Published6 January 2020

- Published31 January 2020