Coronavirus: Why are Australia's remote Aboriginal communities at risk?

- Published

Indigenous Australians often live in overcrowded conditions, making self-isolation difficult

For over a week, some of Australia's remote Aboriginal communities have been severely restricting visitors - to try to keep out the Covid-19 virus.

Now the government is using its Biosecurity Act to bring in these limitations to such places across the country.

Only medical and health staff will be allowed in, as well as police and educational services.

About 120,000 people live in remote communities. They are home to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people - often referred to as First Nation people or Indigenous Australians.

Predominantly in Western Australia, the Northern Territory and Far North Queensland, some communities are several hours' drive from towns - partly down unpaved roads - and are about as isolated as you could imagine.

Has Covid-19 reached these areas?

So far, no. While confirmed Covid-19 cases are rising sharply in Australia, they have been concentrated in the metropolitan areas - with no reports of cases in remote communities.

This is probably not surprising given Australia is in the relatively early stages of the pandemic.

People who get sick have to travel long distances to medical care facilities

The bulk of Australian cases are imported by people travelling from overseas - and remote communities are rarely visited by outsiders.

Joe Martin-Jard, the chief executive of the Central Land Council - which represents Aboriginal people in central Australia - has called for "urgent and drastic action" to keep communities virus-free. The government's measures, announced on Friday, appear to be just that.

Why are these communities being singled out?

Put bluntly, people living there are vulnerable.

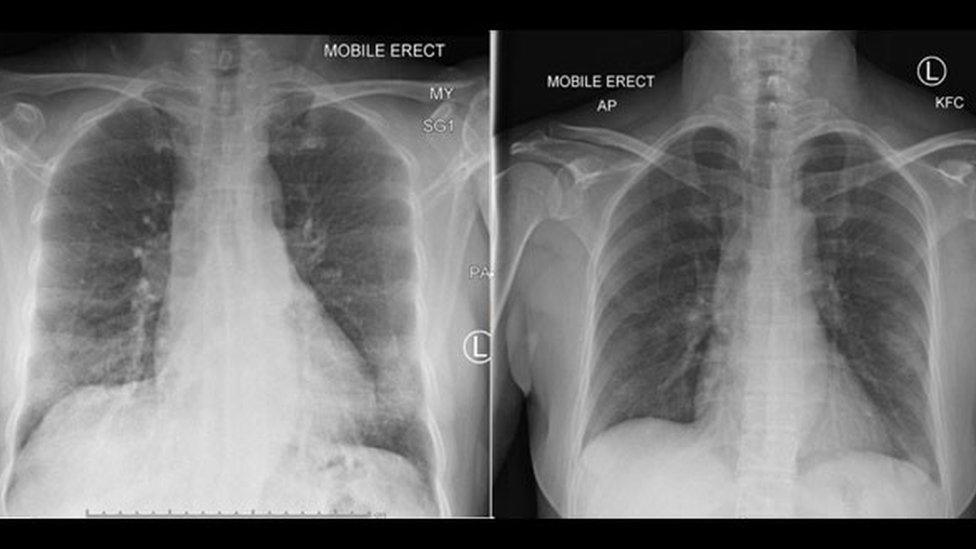

People with underlying medical conditions are known to be at greater risk from Covid-19 - and diabetes and renal failure are more prevalent among Indigenous Australians than the general population.

There are also much higher smoking rates - bad news when dealing with a respiratory condition.

"There is no way that existing medical services can cope if the virus gets into a remote community," says Indigenous rights campaigner Gerry Georgatos. "It's going to be disastrous."

A SIMPLE GUIDE: What are the symptoms?

YOUR THIRD HAND: How do you clean your smartphone?

BORED KIDS: Should you let your children play with others?

A VISUAL GUIDE: Maps and charts to help explain what's going on

Indigenous Australians already have lower life expectancy - the gap between Indigenous males and non-Indigenous males is 8.6 years, according to the latest Closing the Gap report, external. For females, it is 7.8 years.

"An entire generation of elders could be wiped out if we allowed the virus to enter their communities," warned Mr Martin-Jard.

"The death toll even among younger family members would be far higher than for the rest of the nation."

The Western Australian government has said it has plans to evacuate people early should infections occur

Most of these communities have limited if any medical care facilities. When people get sick they rely on visiting doctors, travelling by car to larger towns or, if very ill, being flown out by the services such as the Royal Flying Doctor Service.

Sending in doctors, resources and interim recovery facilities to every Indigenous remote community is essential, argues Megan Krakouer, a lawyer and Indigenous health and suicide prevention outreach worker.

And earlier this week, the National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation said deploying the army should also be considered,

The problem of overcrowding

While being remote may be beneficial in avoiding the virus, that same set-up makes things difficult if and when it hits.

"The contagion effect will spread throughout the whole of the community within less than 48 hours as everyone is in walking distance proximity," says Ms Krakouer.

If somebody is confirmed as having Covid-19 but not especially unwell, they are told to self-isolate for 14 days.

First Nations people have been urged to scale down large gatherings

The same applies for people with symptoms, or who have recently arrived from overseas.

But in small communities such isolation is near impossible given extreme overcrowding.

"Many have nowhere to isolate to," says Ms Krakouer. Many are homeless and rely on staying with friends and family, she says, with 10 or more people living in a house not uncommon.

"There needs to be a better understanding about the grim reality."

Why is there usually community movement?

One of the oldest traditions of First Nations people is the gathering for funerals - known as "sorry business" - that can often attract crowds of 500 people or more, many travelling from larger towns or other remote communities.

Various state governments had already been urging communities to scale down such events, but that's likely to be a losing battle, says Ms Krakouer.

"Cultural practices and structures of kinship are very important. We will not disobey their cultural laws," she tells the BBC.

More on the coronavirus in Australia:

The new restrictions will make it impossible for outsiders to attend.

"Sadly, communities need to rethink attending funerals in large numbers at this point in time," says Ben Wyatt, the Aboriginal affairs minister in the Western Australian government.

People are often also tempted to leave their community for practical reasons such as shopping. Community stores do exist but can cost 50% more than supermarkets in larger locations.

What else has been announced?

The restrictions of who can go in and out is the strongest measure yet. Other policies already unveiled include measures to screen workers going into the remote areas.

The Western Australian government has said it has plans to evacuate people early should infections occur.

And it has promised mobile respiratory clinics to respond to outbreaks in places without hospitals or other health services.

A new service to offer phone and online consultations will be available to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders aged over 50 (as well as non-Indigenous Australians over 70).

But campaigners have pointed to poor communications as well as language issues that need to be overcome.

"There will undoubtedly be people in these communities who have not even heard of coronavirus," says Mr Georgatos. "That's the reality we're up against."

- Published20 March 2020

- Published17 March 2020

- Published17 March 2020

- Published11 February 2020

- Published8 February 2018