Covid in Sydney: Communities feel under siege as troops deployed

- Published

Police Minister David Elliott (R) has defended the use of the army

"If the objective was to frighten the hell out of the community, I can guarantee you they have done that."

Dai Le, a local councillor in Sydney, is speaking angrily about the deployment of 300 military personnel to the city's streets this week.

Her constituency, Fairfield, is one of eight areas in Sydney considered the epicentre of Australia's biggest Covid outbreak in a year.

These poorer and ethnically diverse suburbs in Sydney's west and south west are home to about two million residents. Many are considered essential workers in food, health and other industries.

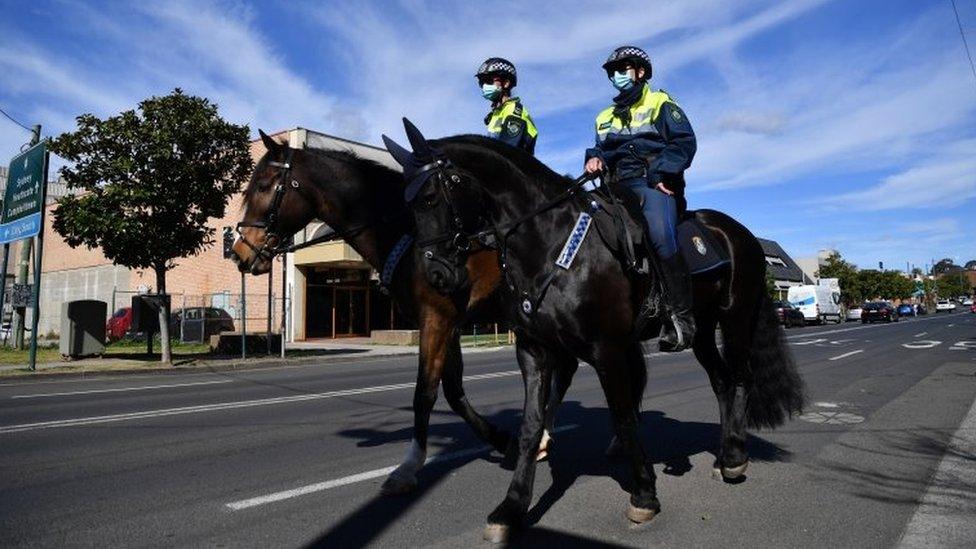

The soldiers arrive almost a month after police deployed an extra 100 officers to the area to enforce lockdown rules.

"I feel we've been treated like second-class citizens," Ms Le says.

"They have killed people's confidence, they have triggered so much fear. What is this message? What is it doing to a community that's already under siege?"

As Sydney scrambles to contain a Delta outbreak that has grown to more than 4,000 active cases and 27 deaths, these suburbs have been put under harsher restrictions than elsewhere.

A citywide lockdown will last until at least 28 August. But unlike other Sydneysiders, these residents have been told to wear masks even outdoors. They cannot travel more than 5km (three miles) when leaving home for essential reasons, less than the 10km afforded to others. There are also stricter limits on who can work.

Police numbers have swollen in Sydney's west and south west

New South Wales (NSW) authorities say these measures are designed to stop infections in the worst-hit areas, with the virus spreading from workplaces to large households.

Police Minister David Elliott told local media a small minority of Sydney residents thought the rules "didn't apply to them".

Dai Le calls the measures "authoritarian". She and other critics have accused authorities of double standards, arguing Sydney's affluent eastern suburbs such as Bondi - where the outbreak began - have been treated differently.

"It feels like an invisible wall has been created around these eight local government areas," she says. "The thing that enrages me is that we did not even start it."

An 'extra level of anxiety'

Arwa Abousamra, an author and Arabic interpreter, also lives in south-west Sydney, where a large portion of people have Middle Eastern, Vietnamese and Chinese heritage. She says she and many in the community have felt on edge.

"I have seen police every single time I've left my home," she says. "I have not been stopped, but I can honestly tell you I feel anxious leaving, almost practising what I'm going to say to a police officer when they stop me.

She acknowledges police have a "very difficult job", but argues it shouldn't be this one: "It's always been a health and resources matter. I think the army is just going add that extra level of anxiety for people."

Arwa Abousamra says some communities are being left behind

Many refugees and asylum seekers live in Sydney's west and south west. Having escaped war-torn countries and oppressive regimes, encounters with the military or law enforcement can be traumatic.

"Police presence [has] caused a lot of angst among members of the community who come from those parts of the world where the police would have been an extension or an arm of the regime they were escaping," Ms Abousamra says.

Dr Omar Khorshid, the president of the Australian Medical Association, argues restrictions should be the same across Sydney.

"Simple rules that apply to everyone have a much better chance of working than focused complex rules," he tweeted.

What makes the situation in these areas even more complicated is the language barrier. Many families don't speak English as a first language. In the past few weeks, state government rules have changed fast and often; all in a language many do not speak fluently.

More on Covid in Australia:

"When addressing Australians, we need to be speaking to all Australians in real time," Arwa Abousamra said.

"How do we expect them to adhere [to rules] if we're… not speaking their language?"

There is now simultaneous translation in Arabic and other languages on local TV channel SBS. The state government has also issued multilingual messages about vaccines. But many say it's all come a bit late.

Ms Abousamra says she works with many asylum seekers and refugees who have no established networks in the community. She worries about their ability to access accurate information: "Who do they call?"

Many locals feel authorities are not addressing their needs, she adds. "I think that's the first thing that communities tend to feel is lack of trust, and that's very risky."

Livelihoods in lockdown

Some families have even been too afraid to seek medical assistance.

After a south-west Sydney man in his 60s died in his home last week, NSW Health Minister Brad Hazzard said: "It is a terrible situation [when households] are not coming forward when one of their number is ill."

Mr Hazzard added that some families were worried about household income if they became exposed to the virus and could not work. The federal government has recently increased support payments for people in lockdown.

But Dr Jamal Rifi, a GP in south-west Sydney, says economic disadvantage remains a key factor. "People need to go to work every morning to earn a living. They don't have the luxury of staying and working from home."

Dr Jamal Rifi (R) is urging people in his area to get vaccinated

Australia's vaccination rates are among the lowest of nations in the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Less than 20% of the population is fully vaccinated.

State officials have asked Sydneysiders to get their jabs urgently, especially in the eight hotspots.

But just 14.6% of people in south-west Sydney are fully vaccinated, according to data released this week, external. That's the lowest percentage of anywhere in the city.

Part of the reason extends beyond language and other barriers. People in south-west Sydney are "younger than the state's average", Premier Gladys Berejiklian said on Tuesday. "Until recently, the health advice precluded a lot of people [from] coming forward and getting vaccinated."

But Dai Le says many locals are "scared of vaccines". Dr Rifi adds that his main focus in the community is encouraging people to be vaccinated.

The main concern in their areas is that the virus is still spreading among families and in workplaces.

Australia’s vaccine rollout is a ‘colossal failure’, ex-PM Malcolm Turnbull tells the BBC

However, Ms Abousamra says that those flouting the rules are a minority and that one thing the state government failed to understand is the make-up of the families in these areas.

"They're bigger families. So the numbers are not always a reflection of people doing the wrong thing," she says.

Ms Le says people are worried about their livelihoods and how long the lockdown will last. They also fear further restrictions being imposed on the area.

"Instead of sending the military, why don't they send more vaccines?" she says.

"People are beyond overwhelmed now. [They think] 'what more will the government do to us?'"

- Published29 June 2021