Julian Assange: Does Wikileaks founder have a powerful ally in new Australian PM?

- Published

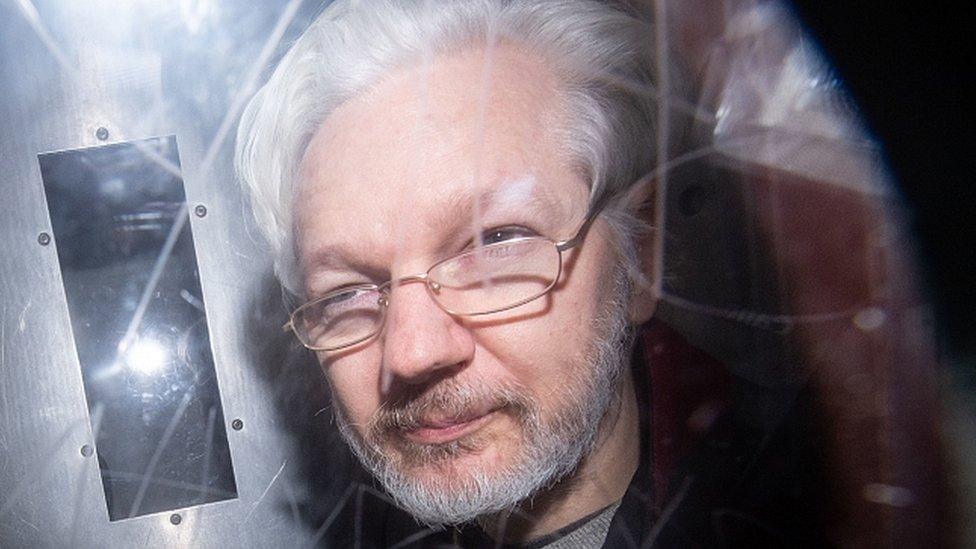

Julian Assange has been almost 10 years without freedom

After more than a decade spent trying to avoid extradition from the UK, Julian Assange is running out of time and options.

But with the election of a new government in his native Australia last month, his supporters hope he has a new, powerful ally.

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese has previously spoken against Mr Assange's incarceration, and the activist's family are counting on him to put pressure on the UK as the deadline for a critical deportation decision looms.

The Wikileaks founder is wanted in the US over classified documents leaked in 2010 and 2011, which it says broke the law and endangered lives.

But Mr Assange's supporters say the reports exposed US wrongdoing in the Iraq and Afghanistan wars and were in the public interest.

After a long legal battle in the UK, the courts in April referred the US extradition request to the Home Secretary for her final decision.

Priti Patel has until 19 June - exactly 10 years since Mr Assange was last free - to make it.

"At this point, until Priti Patel signs off, it is entirely political. And so it's open to a political solution," says Mr Assange's brother, Gabriel Shipton.

So what - if anything - can Australia do?

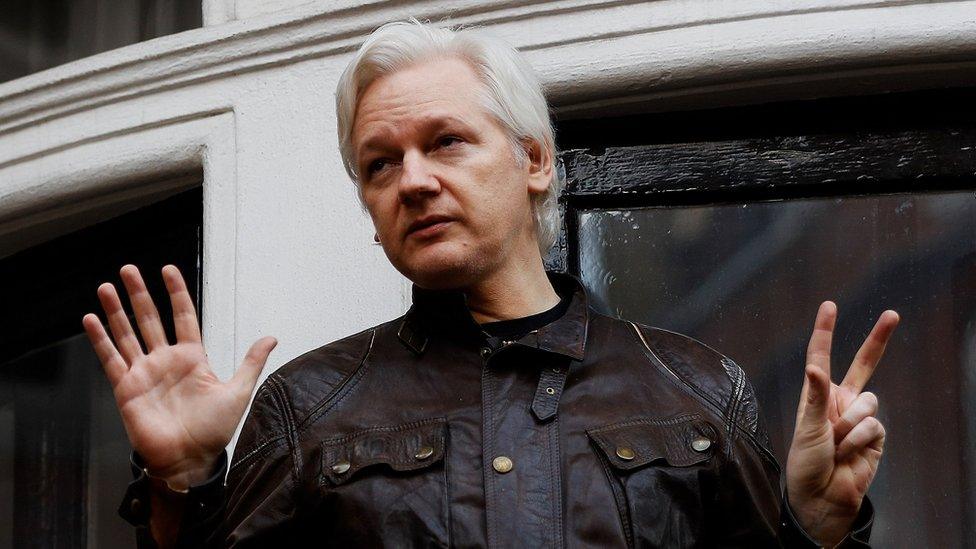

Mr Albanese - a signatory to the Bring Julian Assange Home Campaign petition - last year said the 50-year-old should be freed.

"Enough is enough," he said at a party room meeting.

"I don't have sympathy for many of his actions but essentially I can't see what is served by keeping him incarcerated."

Anthony Albanese has previously spoken in support of Mr Assange's release

But since taking office Mr Albanese has been coy on what action his government will take on the matter.

When asked about Mr Assange at a press conference last week, he said "not all foreign affairs is best done with the loud hailer".

The comment has buoyed Mr Assange's family, with Mr Shipton saying it represents a huge shift from the position of previous governments.

"[They] have always said 'Julian is receiving consular assistance' and said things like 'this as a matter of for the UK courts and the government cannot interfere'."

"[They] have become complicit in Julian's persecution and imprisonment by sitting on their hands."

He says the family is finally confident Australia is having conversations "behind closed doors", which they hope could be pivotal.

Gabriel Shipton (right) has advocated for Mr Assange's release alongside his father John Shipton

Donald Rothwell, a professor of international law, agrees the Albanese government's election presents a "reset" opportunity and says any intervention could have sway.

Though there has been little transparency, Australia's previous government seemingly did not seek to raise the matter at a high level, he says.

It's a particularly sensitive problem as it involves two of Australia's closest allies and - as the previous government often pointed out - it is a legal matter.

"To degree, they're right," says Prof Rothwell, from Australian National University.

"That doesn't mean to say that - at this very pointy end - the Australian government is not able to start to make political representations."

Mr Albanese is seen as likely to quietly appeal to both the UK and US through diplomatic channels.

"There was some speculation that the Biden presidency could see the government take a different view on Assange," Prof Rothwell says.

"There's really been no indication. But it needs to be understood that the power to halt this matter clearly rests with President Biden. The US could end it tomorrow."

UK precedent to deny request

In 2000 the UK decided that former Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet should not be extradited to Spain to face charges over human rights violations on health grounds.

So regardless of any Australian pressure "there is a significant precedent in another very, very high profile matter," Prof Rothwell says.

And in 2012, the UK refused a US extradition request for British computer hacker Gary McKinnon, judging it to be "incompatible with his human rights".

"He had similar depression and Asperger's syndrome as Julian and Theresa May rejected that extradition because the care that he needed he would not be able to get in the US prison system," Mr Shipton says.

Protestors across the world have called for the UK Home Secretary to deny the extradition request

But the expectation of Mr Assange's legal team is that Ms Patel will sign off on the extradition order anyway, he adds.

Mr Assange is still able to appeal to the High Court and raise his case at the European Court of Human Rights.

Legal battle already spans a decade

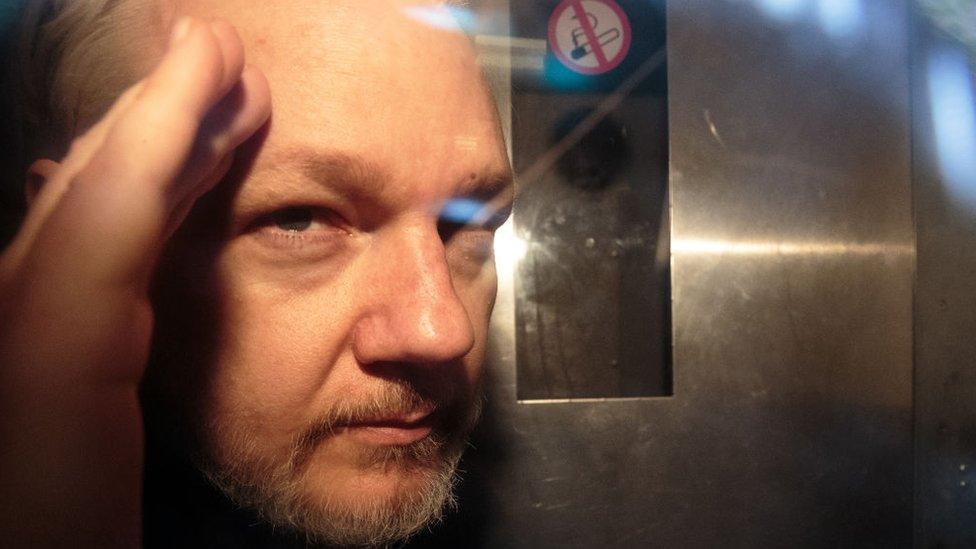

In 2012 Mr Assange sought asylum in the Ecuadorian embassy in London, fearing US prosecution.

But after seven years confined to the embassy, he was removed and arrested in 2019 after Ecuador withdrew his asylum status - citing alleged bad behaviour.

He has since been held in London's Belmarsh Prison, where his health has deteriorated. His legal team argues he will die if he's sent to the US.

In January 2021, a judge sided with Mr Assange's team, ruling he could not be extradited because there was no guarantee that American authorities could look after him.

The High Court then reversed that decision last December, saying that the US had since provided sufficient assurances that Mr Assange could be safely cared for.

Watch: From 'teenage hacker' to fighting US extradition - the Julian Assange story

Mr Assange faces a possible jail term of up to 175 years in the US, his lawyers have said.

However the US government told the High Court the sentence was more likely to be between four and six years - and it would even consider sending him to an Australian jail.

'Threat to democracy'

Mr Shipton argues much is at stake - including global press freedoms.

Mr Assange's supporters say he is a publisher and a journalist and his extradition would have a chilling effect.

"People should be able to expose war crimes, they should be able to publish about government corruption or torture.

"Julian's prosecution means that… journalists can't do their job, and that's a threat to democracy."

Speaking about his brother, he adds: "This endless Snakes and Ladders legal situation takes its toll on him. It's punishment by process.

"This man is suffering."

You may also be interested in:

Julian Assange: ""

Related topics

- Published20 April 2022

- Published23 March 2022

- Published10 April 2022

- Published25 June 2024