James Geoffrey Griffin: The child abuse scandal that shamed Tasmania

- Published

Griffin's systemic abuse was uncovered after Tiffany Skeggs went to police

"All of the people that knew me as a child… they all tell me that I was this joyful, energetic, happy-go-lucky child.

"[But] I don't remember my child self. I don't know who she was when she was happy, before she was traumatised."

From age 11, Tiffany Skeggs was groomed and raped by a man 47 years her senior, in Tasmania, Australia.

He was a nurse and a well-liked community volunteer - a paternal figure, she said, who filled a hole left by her father's death years earlier.

"I saw him as a hero. He made it seem like I was the only person on Earth," she told an inquiry.

Ms Skeggs wasn't the only child James Geoffrey Griffin had groomed in that way. Over four decades, he brazenly exploited and abused many girls.

One was the child of a colleague and friend. Another was a relative he bragged online about sedating and raping. Several were his patients. Another girl had a disability and was non-verbal - her mother made allegations on her behalf.

Exactly how many people Griffin abused is unknown. Authorities say they know some haven't come forward.

How was this allowed to happen?

The first allegations against Griffin date back to the late 1980s, when he was in his 30s. It would take 30 years for him to be arrested.

In that time, he gained access to children primarily through his role as a nurse on the paediatric ward at Launceston General Hospital and as a massage therapist for junior sporting teams.

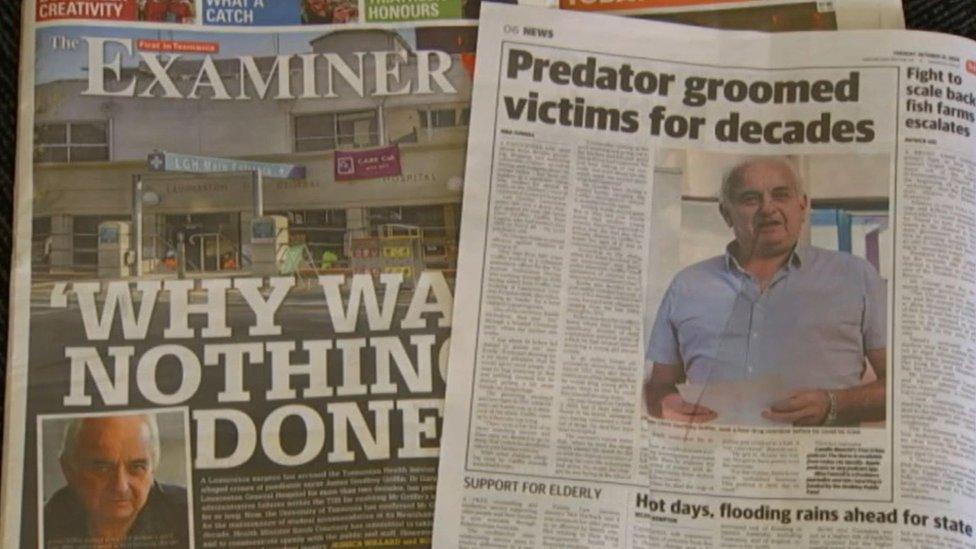

Griffin's case sparked outrage in Tasmania

For years, parents, colleagues and even strangers tried to alert authorities to the risk Griffin posed. But only in 2019 when Ms Skeggs disclosed her abuse did police investigate properly.

By October that year Griffin, then 69, had been charged with abusing four children. He died by suicide weeks later.

A Tasmanian inquiry is now investigating how a litany of complaints and red flags were overlooked. During public hearings which concluded this month, it heard Griffin received his first written warning about problematic behaviour in 2004.

The behaviour only escalated, and complaints began piling up. Among them were reports he had been cuddling a pre-teenage girl at the hospital, was giving his phone number to patients, and had given an 11-year-old a "wet kiss" on the forehead.

He was counselled and warned, but ultimately maintained his access to vulnerable children.

Most extraordinarily, the hospital overlooked a disclosure by one of their own staff members that she had been repeatedly abused by Griffin from age seven.

In 2011, social worker Kylee Pearn told her boss and HR representatives what had happened to her. It followed a sleepless night on the paediatric ward with one of her own children - she had been too scared to leave the child alone.

"I just thought how incredibly unfair it was that I could protect my child, but no one else in this ward knew that information," she told Tasmania's Commission of Inquiry into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse.

There were multiple complaints made against Griffin while he worked at Launceston General Hospital

Other staff spoke up too. One senior nurse told the inquiry she had taken it upon herself to allocate young, female patients to other nurses wherever possible, after her concerns about Griffin fell on deaf ears.

Another colleague, Will Gordon, formally reported Griffin but his complaint was deemed "unsubstantiated" without even speaking to the girls involved.

Griffin's behaviour was constantly excused, Mr Gordon said. "It would be: 'Jim is Jim. That's just who he is.'"

Only when police reported finding Griffin in possession of child abuse images that appeared to be taken inside the hospital was he suspended from work.

The public hospital had a culture of fear and cover-up, senior staff told the inquiry.

Some revealed they had no training in identifying grooming behaviour and weren't aware of mandatory reporting obligations, or how to escalate their complaints.

The head of Tasmania's health department - which oversees the hospital - recently made an emotional apology, saying she was "personally horrified" by the evidence and the "lack of empathy and humanity" shown to survivors.

"While my words alone will not heal the hurt of all those that have suffered - nor will words alone comfort those [who] will never know if they or their children were victims - I will do my very best to lead [the department] to right the wrongs of the past," Kathrine Morgan-Wicks said.

Failures by police and others

Police were alerted to Griffin's behaviour even earlier, on at least five separate occasions.

In 2000, a man who had bought a laptop from Griffin told police it contained possible child abuse material. His email was ignored.

The concerned man contacted police again the next year, writing: "I do not want to think he is working in a kids ward in Tasmania unsupervised, given what I have found."

Police checked the laptop and found the images that remained on it - of children in bikinis - were "morally" concerning but legal. No further investigation was carried out.

Then in 2009, a man reported seeing Griffin taking "upskirt" photos of young girls while working as a medic on a popular ferry. Police searched his house, finding he cleared his internet browsing history daily and had a large cache of photos of young girls.

Griffin worked on the Spirit of Tasmania, a ferry service to Melbourne

The matter was "filed for intelligence" and no further action was taken.

In the years that followed, authorities were advised two people had disclosed past child abuse by Griffin, and other concerned adults - including Ms Skeggs' mother - made complaints. On both occasions child safety services and police failed to investigate adequately.

Then in 2015, police were told Griffin was discussing child abuse online. They wanted more information about the tipoff - but when the person provided evidence, their email wasn't even opened.

Tasmania's police commissioner apologised to Griffin's victims last year, saying they had been "let down by the deficiencies in our systems and investigative processes".

'No way in hell' anyone did enough

Australia has long been reckoning with the problem of child sexual abuse.

Harrowing stories from survivors shaped a national inquiry which began in 2013 and found shocking institutional failures.

The royal commission was supposed to improve how Australia dealt with abuse cases.

But years later, Ms Skeggs' case forced Tasmanian authorities to look at themselves again.

Tiffany Skeggs holds hands with a friend at the opening of the Tasmanian inquiry

Its inquiry will make recommendations and may make adverse findings against individuals, possibly informing prosecutions.

A review into Launceston General Hospital has already been announced, and police have vowed changes, external after a separate review of their actions.

But Ms Skeggs, now 25, said all systems concerned with child safety need improvement - the entire community failed her.

"Did any of them do enough? There's no way in hell. The phrase that I'll hate for the rest of my life is: 'That's just Jim.'

"It should never be up to or be the responsibility of an 11-year-old child or any child to protect themselves, and to this day it remains that way."