Australia child abuse inquiry finds 'serious failings'

- Published

Abuse survivor Andrew Collins recounts his story

A five-year inquiry into sexual abuse in Australia has released its final report, saying institutions had "seriously failed" to protect children.

The royal commission, Australia's highest form of public inquiry, heard more than 8,000 testimonies from victims of abuse.

The accusations covered churches, schools and sports clubs over decades.

Among more than 400 recommendations, the report calls on the Catholic Church to overhaul its celibacy rules.

"Tens of thousands of children have been sexually abused in many Australian institutions. We will never know the true number," the report said.

"It is not a case of a few 'rotten apples'. Society's major institutions have seriously failed."

Since 2013, the royal commission has referred more than 2,500 allegations to authorities.

The final report, released on Friday, added 189 recommendations to 220 that had already been made public. The proposals will now be considered by legislators.

Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull said "a national tragedy" had been exposed.

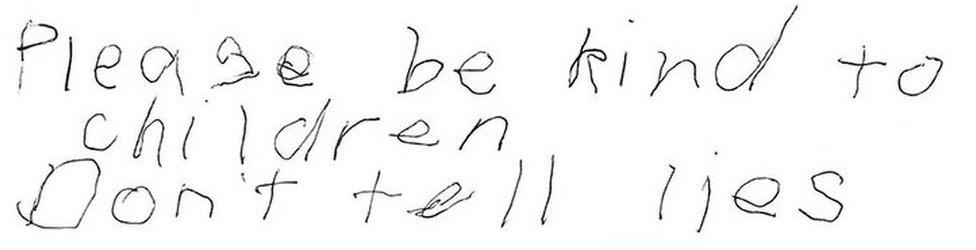

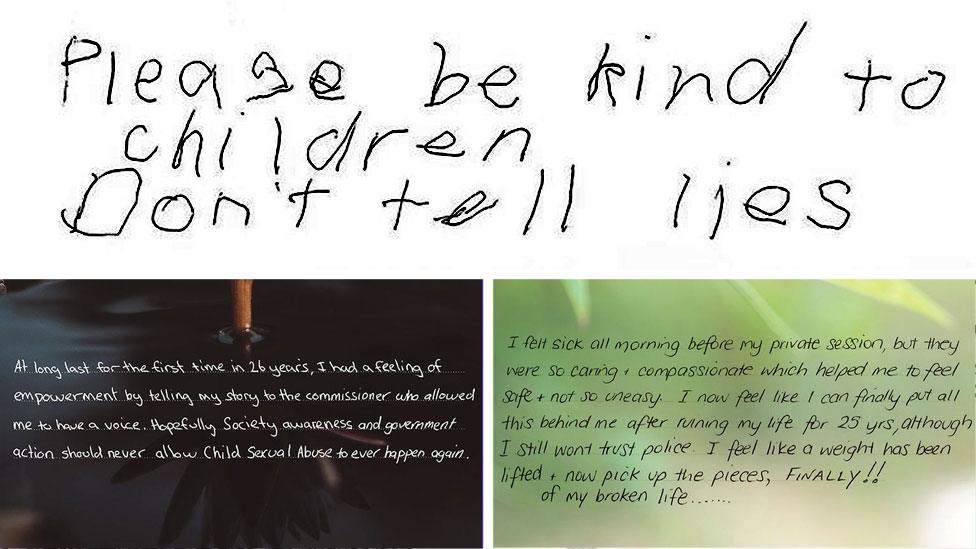

Letters from survivors

Who did the inquiry speak to?

The Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse had the power to look at any private, public or non-government body involved with children.

It was contacted by more than 15,000 people. More than 8,000 victims told their stories, many for the first time in private sessions.

The commission also received more than 1,300 written accounts and held 57 public hearings across the nation. Allegations were raised against more than 4,000 institutions.

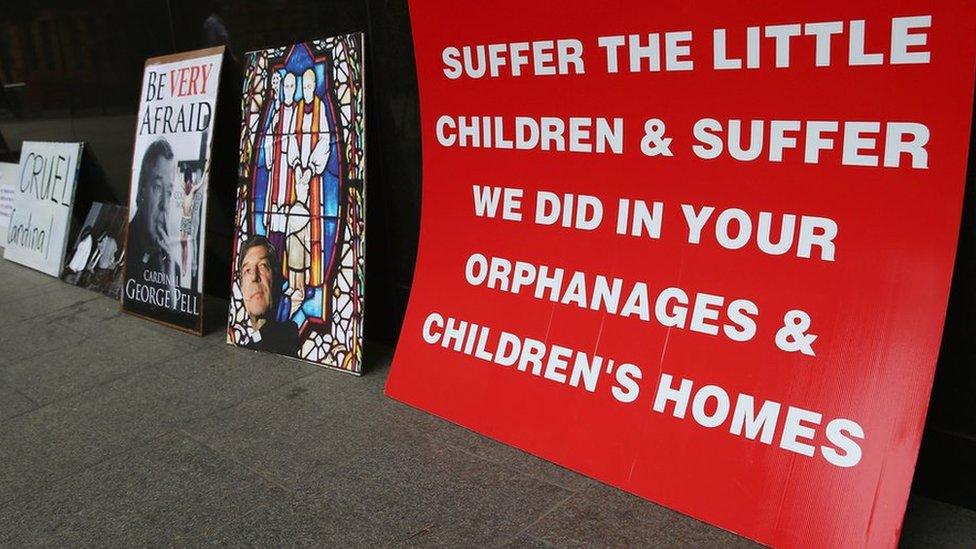

Religious ministers and school teachers were the most commonly reported perpetrators, the report said. The greatest number were in Catholic institutions.

What did it recommend?

The commission had previously recommended that Catholic clerics should face criminal charges if they fail to report sexual abuse disclosed to them during confession.

The final report on Friday urged Australian Catholic bishops to petition the Vatican to amend canon law to allow priests to report such disclosures.

It also said the Catholic Church should consider making celibacy voluntary for priests because while it was "not a direct cause of child sexual abuse", it had "contributed to the occurrence of child sexual abuse, especially when combined with other risk factors".

The BBC's Hywel Griffith in Sydney said applying mandatory reporting to confession would trigger debate across the Catholic world, and has raised questions for bodies far beyond Australia's borders.

Among its other major findings, the inquiry recommended:

A nationally implemented strategy to prevent child sex abuse

A system of preventative training for children in schools and early childhood centres

A national office for child safety, overseen by a government minister

Making it mandatory for more occupations, such as religious ministers, early childhood workers and registered psychologists, to report abuse.

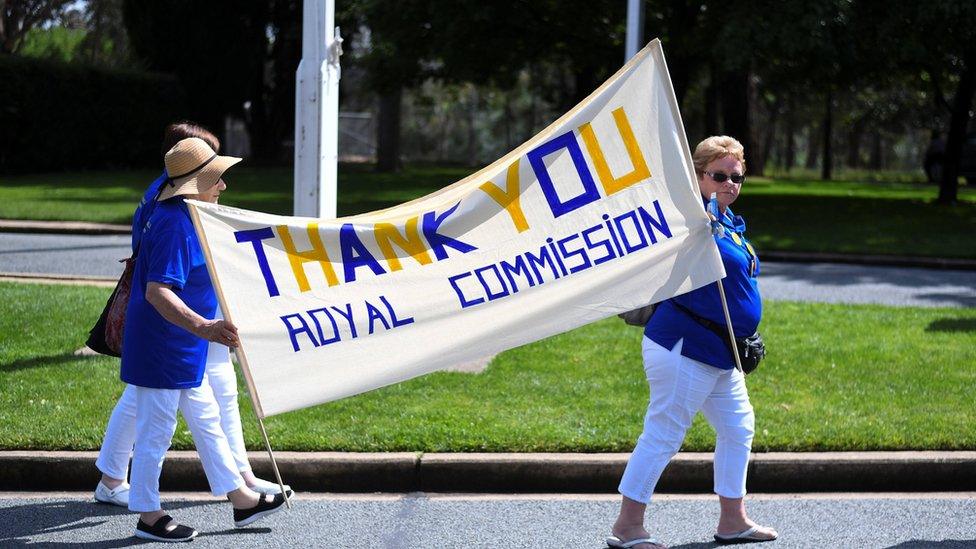

Supporters of the inquiry gather in Canberra on Friday

How have institutions reacted?

Throughout the inquiry, many leaders of institutions admitted failures and apologised to victims on behalf of their groups.

On Friday, the president of the Australian Catholic Bishops Conference, Archbishop Denis Hart, offered an "unconditional" apology.

"This is a shameful past, in which a prevailing culture of secrecy and self-protection led to unnecessary suffering for many victims and their families," he said.

However, he rejected changing the rules on confession. "The seal of the confessional, or the relationship with God that's carried through the priest and with the person, is inviolable," he said.

On the call for voluntary celibacy, he said it was up to the Vatican to decide. "It's a discipline which the church can change," he told Fairfax Media., external

But Sydney's Catholic Archbishop Antony Fisher told reporters that child sexual abuse was "an issue for everyone, celibate or not", saying the problem also occurred in families and institutions with non-celibate clergy.

Australia's most senior Anglican figure, Melbourne Archbishop Dr Philip Freier, apologised for "our failures and by the shameful way we sometimes actively worked against and discouraged those who came to us and reported abuse".

Survivor accounts: Extracts from the final report

"Gerry Ann" said she "lived in a climate of fear" at the orphanage where she grew up. "My time at [the orphanage] robbed me of my innocence, and set the benchmark of who I would become: frightened, petrified, scared, fearful, not worthy, introverted, isolated, segregated, sad and constantly suicidal."

"Toby" shared a cabin with four other boys at a primary school camp. During shower time he was sexually abused by two of the boys he was sharing his cabin with. He told his mother that the abuse had involved "putting penises in his bottom", and that he had told this to the deputy principal at camp.

"Brianna" has spent her childhood in out-of-home care. She said at age five, she remembered being physically beaten. Her foster father, "Sherman", beat her with a pool cue as her sister hid under the table. He began sexually abusing her soon after she moved in. Brianna said that on at least one occasion, her foster mother encouraged Brianna's sister to sleep in Sherman's bed.

Like many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander survivors in out-of-home care, "Raquel" was subjected to harsh treatment by the foster family, describing them as "cruel pigs". She said she was whipped with a bamboo stick among other physical and emotional abuses.

*Names have been changed in the report to protect the identities of the survivors.

- Published15 December 2017

- Published14 December 2017

- Published20 December 2016

- Published14 August 2017