How Australia wrote the 'stop the boats' playbook

- Published

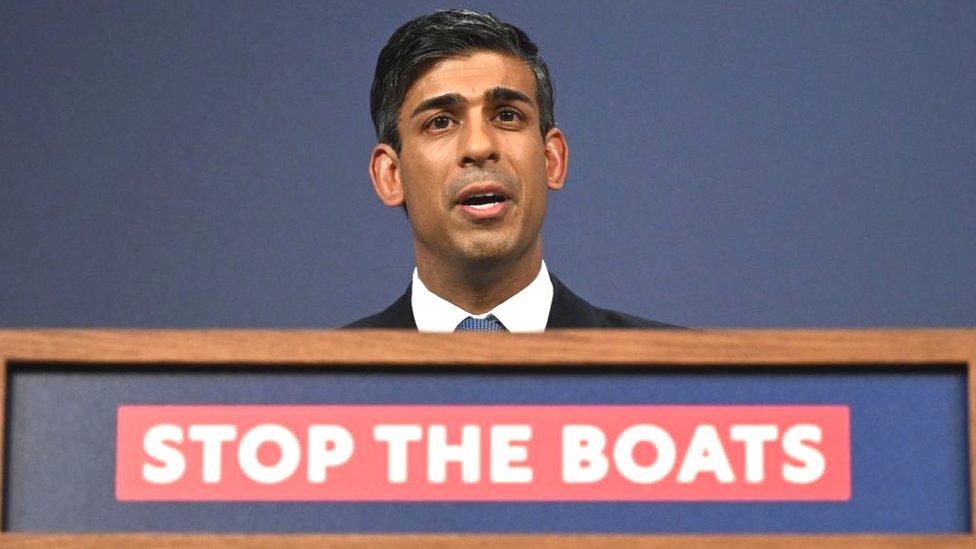

UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak announcing his "stop the boats" policy

The UK government is banking on its new migration bill to stem the flow of small boats crossing the English Channel. The policy's headline-grabbing slogan is identical to that used in Australia a decade ago.

For many Australians, hearing UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak promise to "stop the boats" was a moment of deja vu.

The same words were used by former Australian PM Tony Abbott in 2013 - helping him win an election.

The situation in Australia was similar to the one facing the UK now.

Last year, more than 45,000 migrants crossed the English Channel in small boats to reach the UK. In 2013, Australians watched as 20,000 migrants made similar perilous journeys from countries like Indonesia, Iran and Sri Lanka. Scores died en route.

And so, during his winning general election campaign, at the height of the crisis, right-wing Liberal Party leader Mr Abbott promised to implement border rules even tougher than the outgoing Labor government. Under his "Operation Sovereign Borders" policy, migrant boats would be intercepted and either returned to where they travelled from or those on board taken to overseas island detention centres.

Human rights groups have long criticised Australia's border policy - but other countries, like Denmark, have been inspired.

"Australia absolutely wrote this playbook - and we're still writing it," says Australian National University politics lecturer Kim Huynh, whose family fled Vietnam for Australia via boat in the 1970s.

In the UK, the Conservatives have already adopted an "Australian-style" points-based immigration system - but to what extent are they following Australia this time?

More than just three words

The UK copied word-for-word Australia's "stop the boats" slogan, but the broader rhetoric - the tough language - is also strikingly similar.

Australia's former Home Affairs Minister Peter Dutton has suggested several times that the country has blocked murderers, rapists and paedophiles from seeking asylum by boat. And in 2017, he faced a backlash after suggesting that many asylum seekers who travelled to Australia were "fake refugees" trying to "rip the Australian taxpayer off".

In the UK, Home Secretary Suella Braverman has controversially referred to her job as being "about stopping the invasion on our southern coast". And - while numbers of Albanians arriving fell significantly at the end of 2022 - she told MPs last week that many of the migrants were young men "from safe countries like Albania" who were "rich enough to pay criminal gangs thousands of pounds for passage".

That kind of language resonates in both Australia and the UK, partly because their populations have - to differing degrees - "island mindsets", Dr Huynh says. "A lot of the critics would say [the rhetoric] works politically because it stirs up fears of outsiders."

Former Australian PM Tony Abbott described his border policy as "decent, humane and compassionate"

And then, there is the policy rationale - the public marketing. Both countries have stressed the humanitarian benefits.

Ms Braverman told the Commons last week that the UK government was acting with "determination", "compassion" and "proportion".

While in 2014, Mr Abbott spoke of a policy that was saving lives. "As long as the boats keep coming, we will keep having deaths at sea," he said. "So, the most decent, humane and compassionate thing you can do is to stop the boats."

Policy similarities?

The UK's current migration issues aren't identical to the ones that faced Australia 10 years ago - and so the policy touted by Westminster does not exactly mirror that of Tony Abbott's coalition administration in Canberra. But comparisons can be drawn.

Offshore processing

Australia's policy was to send people arriving by boat to detention centres - in Papua New Guinea and the Pacific island of Nauru. Migrants were offered return to their home countries, and recognised refugees were offered resettlement in another one. As boats have stopped arriving, no-one has been sent offshore since 2014

The UK government would like to send those arriving illegally back to their home country if it is "safe" - or to a third country where claims to seek asylum in the UK or that third country would be processed. Only under-18s, those medically unfit to fly, or at risk of serious harm in the country they are being removed to would be able to delay removal. So far, Rwanda is the only third country to agree to take migrants - processing 200 people a year at first - but legal challenges mean no-one has been sent there yet

Mandatory detention

Australia's policy was, and still is should any boats arrive, to detain people arriving in small boats indefinitely - even once sent offshore. Most were freed only when their claim for asylum was resolved and they were either deported or added to waitlists for resettlement in another country

In the UK, under the proposed law migrants could be held for as long as the home secretary considers there to be a "reasonable prospect of removal"- with no chance to apply for bail for at least 28 days. However, once removed to Rwanda for processing they would be free to come and go

A boat carrying asylum seekers near Christmas Island in 2012

Ban on citizenship

The Australian government's policy - although not enshrined in law - is that anyone sent to an offshore processing centre will never be resettled in Australia, even if they are recognised as a refugee

People removed from the UK would be blocked - by law - from returning, or seeking British citizenship in future

But arguably, the most important aspect of Australian policy in 2013 was the reintroduction of so-called "turnbacks" at sea - having been used previously between 2001-03. Defined by the Abbott government as "the safe removal of vessels from Australian waters, with passengers and crew returned to their countries of departure", boats were prevented from reaching shore. There was a dramatic reduction in arrivals by sea.

In April 2022, the UK government dropped plans to return small boats in the Channel back to France, after the Royal Navy refused to carry out the operations. The military conducted trials of practices similar to those performed by Australian armed forces but declared them "inappropriate".

The UK announced on 10 March it would give Paris almost £500m over three years - to fund extra police patrols on beaches and a new detention centre in northern France.

Did Australia's policies work?

While Operation Sovereign Borders remains controversial, both major parties in Australia - the right-wing Liberals and left-wing Labor - still support the policies behind it. They argue the country's success lies in the policy mix working together to deter asylum seekers.

But there are those who believe the offshore processing had little - if any - impact.

It was re-introduced by Labor in 2012 and the facilities in Papua New Guinea and Nauru quickly filled up.

"Two months in, the government was saying, 'We've already had more people arrive than we'll ever be able to accommodate offshore, and so we're going to start releasing some people into the community in Australia,'" says refugee law expert Madeline Gleeson.

Photo from 2012 showing the asylum-seeker processing facility on Manus Island, Papua New Guinea

And so the Labor government did a reset - emptying the centres and bringing migrants to Australia, before trying again. This time adding a promise that anyone seeking asylum in Australia by boat would never be settled here, even if they were found to be a refugee.

That didn't seem to slow the number of boats either, Ms Gleeson says.

And so when the Liberal-National coalition took over in late 2013, they pivoted to boat turnbacks - something which Labor had opposed - and the number of migrant boat arrivals dropped dramatically.

One boat arrived in 2014, down from 300 the year before, external, and no others have arrived since - though it is unknown how many boats have since been intercepted and returned before reaching Australian shores.

The measures had "restored integrity to Australia's borders", said Home Affairs Minister Peter Dutton in 2015 - but at a price. Best estimates put the cost at A$1bn (£552.4m, $658.7m) a year. There's also the compensation bills the government has footed for the poor treatment asylum seekers have suffered in offshore processing facilities.

A "Welcome Refugees" rally in Sydney on 29 September 2013

"And then there's a cost on the heart and soul of Australia," says Dr Huynh.

Australia's treatment of people in offshore detention, particularly children, has drawn international condemnation - the UN says it amounts to torture.

And the country has also been accused of violating international law by breaking its obligations to refugees and those seeking asylum.

Would similar measures work in the UK?

UK Home Secretary Suella Braverman has conceded the latest plans push "the boundaries of international law". And Australia's former foreign minister and diplomat Alexander Downer - who has advised the UK government on border policy - has admitted the country would have to change its laws and wind back human rights protections to employ the policies effectively.

The UN's refugee agency - the UNHCR - has already said it is "profoundly concerned" by the UK government's latest plan, external, which it says would "amount to an asylum ban".

Ultimately, says Ms Gleeson, the UK will likely have a harder time implementing its proposed policies than Australia did. The UK is also a "totally different place" from Australia, she adds.

Australia also has agreements with several of the countries from where migrants travel, but France has made it clear that such an agreement with the UK is unlikely.

Then there is scale. Even in the peak year of 2013, the total number of boat arrivals in Australia was less than half the current UK annual figure - and they overwhelmed the country's processing system.

"If it was too much for us, how [is the UK] going to have the capacity to do it?" Ms Gleeson says.

And perhaps most critically - she says - while Australia is a signatory to international treaties, it has no legally binding human rights framework, similar to the UK's Human Rights Act or the European Convention on Human Rights. "So I think there is going to be a real legal issue."

Additional reporting by Paul Kerley

- Published13 December 2023

- Published10 March 2023