Peter Bol: Australian runner's doping row could have global impact

- Published

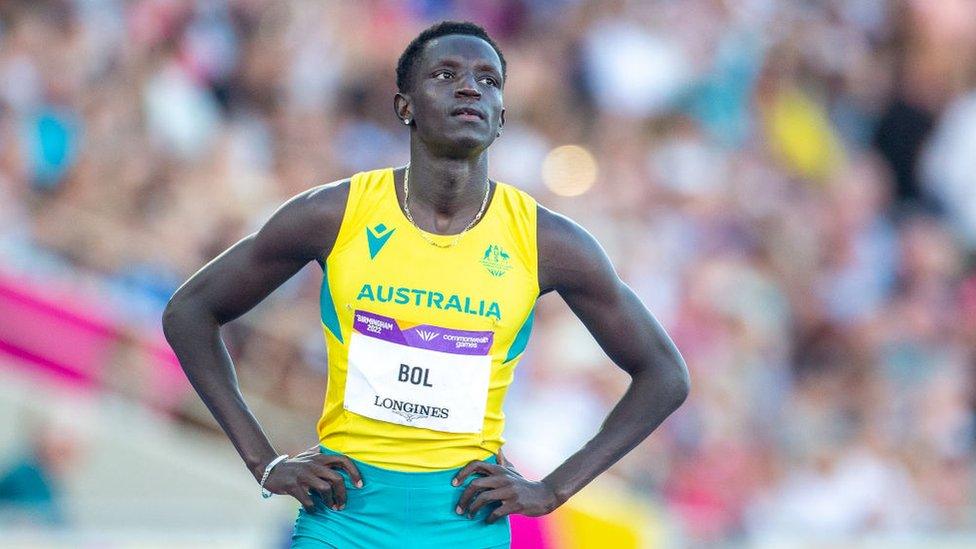

Peter Bol denies cheating - he and experts raise questions about the integrity of some tests

When runner Peter Bol edged ahead of the pack during the men's 800m final at the Tokyo Olympics, it felt like the whole of Australia was cheering him on.

Bol - a Sudanese refugee who arrived in Australia aged eight - was the country's first finalist in the event in 53 years.

Despite slipping to fourth at the final stretch, Bol's gutsy race in 2021 cemented his status as the new darling of Australian sport.

He has continued to impress - but two months ago, his momentum for the next Olympics was shattered and his life upended by what he says are untrue allegations he is a drug cheat.

But Australia's anti-doping regime has also been accused of making "catastrophic blunders" in its handling of his case, which experts say could have ramifications globally.

Shock result

In January, Bol was informed he had failed an out-of-competition drug test and was provisionally suspended - unable to compete or train.

He had returned a positive result for the banned substance erythropoietin.

Better known as EPO, it is a naturally occurring hormone. But when injected in its synthetic form, EPO is a form of blood doping which has been employed by athletes - most famously Lance Armstrong - to aid stamina and recovery.

Cyclist Lance Armstrong was stripped of his titles after it emerged he had used EPO

Bol immediately requested a fresh analysis of his sample, a process that is supposed to be private.

But a week later - just days before he was tipped to be named Young Australian of the Year - his initial result and subsequent suspension was leaked to the media. The runner took to social media to express his "shock".

"It is critically important to convey with the strongest conviction I am innocent and have not taken this substance as I am accused," he said in a statement.

A month later, on 14 February, his back-up sample returned an "atypical response" - meaning it was neither positive nor negative. Experts say it is rare that the two samples do not match.

Bol's provisional ban was lifted immediately, and the runner said he had been exonerated. "The relief I am feeling is hard to describe… the last month has been nothing less than a nightmare," he said in a statement.

But Sport Integrity Australia (SIA) said he had not been cleared and vowed to continue its investigation.

"An [atypical finding] is not the same as a negative test result," its statement said, adding it was not possible to say when the process would conclude.

Bol has said he is still waiting to be interviewed by SIA officials. But last week, his team said two independent laboratories had cleared Bol of ever injecting EPO.

An expert in Canada and a team in Norway analysed the results from Bol's samples. They both found the Australian Sports Drug Testing Laboratory (ASDTL) had erred in the way it performed the test and that it had also read the results incorrectly - mistaking naturally occurring EPO for synthetic.

They concluded Bol's initial sample should never have been deemed positive.

The ATSDL has 20 years of experience in EPO testing and is the only World Anti-Doping Agency (Wada) approved facility in Australia, but Bol's lawyer Paul Greene accused it of "inexperience and incompetence". He demanded SIA drop its investigation and apologise for "catastrophic blunders".

Sporting Integrity Australia and the ASDTL did not answer the BBC's questions about the case.

A global impact?

Catherine Ordway, a sports lawyer and former director at Australia's anti-doping agency, says the situation appears damning and Bol's case could have "major ramifications for other cases around the world".

If the lab did make mistakes during the testing process it could jeopardise its accreditation, says Dr Ordway, who notes other facilities have previously lost permits over a single false positive.

But more importantly, Bol's case has revived doubts over the test itself. A confirmed bungle could call into question EPO test results dating back decades, Dr Ordway tells the BBC.

"The World Anti-Doping Agency expert group is of course saying the test is robust… but [there have been] some serious concerns about it for quite some time," she says.

There are two key ways EPO testing could go wrong, exercise physiologist and biochemist Rob Robergs tells the BBC.

A lot of drug tests are "incredibly sensitive" to small errors, the Queensland University of Technology academic says. But mistakes can also be made in the interpretation of EPO test results, as the process - unlike testing for many other banned substances - does not provide a simple yes or no answer.

Because EPO is a naturally occurring hormone, labs are trying to determine if there is any synthetic EPO.

"When they're making a judgement on that, it's subjective," Dr Ordway says. "They're trying to read it and say: 'Is it outside of normal range?' But how do we determine normal range?"

Some people - often high-performance athletes - have naturally elevated hormone levels, Dr Robergs points out. Others, including Bol himself, have speculated over whether the athlete's genetic and racial background could have affected his results.

It's hard to tell if any of those factors were considered when anti-doping authorities determined the acceptable range of EPO, Dr Robergs says.

"We just don't know… there's a lack of transparency."

Bol says his training ahead of next year's Olympics has been disrupted

Both Dr Ordway and Dr Robergs say Bol's case could undermine confidence in the global anti-doping system and say Wada should review of its current EPO testing procedures.

Both independent laboratories that analysed Bol's test results also suggested the Wada method for EPO testing needs to be amended.

"We need to maintain and restore the trust in the system. Otherwise, if you lose the trust of clean athletes, then the whole system falls down," Dr Ordway says.

But some say the saga should also prompt authorities to consider how they treat athletes accused of doping, given the imperfect nature of the science.

SIA has "very black and white" approach to anti-doping and are "ruthless" in their pursuit of perceived cheats, sports historian Stephen Townsend tells the BBC.

"This case casts doubt… on whether or not they should assume athlete guilt before they assume athlete innocence," says Dr Townsend, from the University of Queensland.

It's been a messy saga for both Bol and SIA, and any future resolution is unlikely to be much different, he says. "SIA are the sports police. It's their job to protect the sanctity of sport and protect this idea of a level playing field.

"Whilst they probably recognise that they don't have much chance of pursuing Bol for a doping violation in this case, they also cannot admit that they got it wrong."

That leaves Bol with a cloud over his head that he admits he may never be able to shake.

"There's always going to be speculations," Bol said an interview with Seven last month.

"[When] I perform well, people are going to think you're on the juice. And if I don't perform well, people are going to think you got off it."

Related topics

- Published5 August 2021

- Published4 June 2015