Australia tries to stop an epidemic of violence against women, starting with schools

- Published

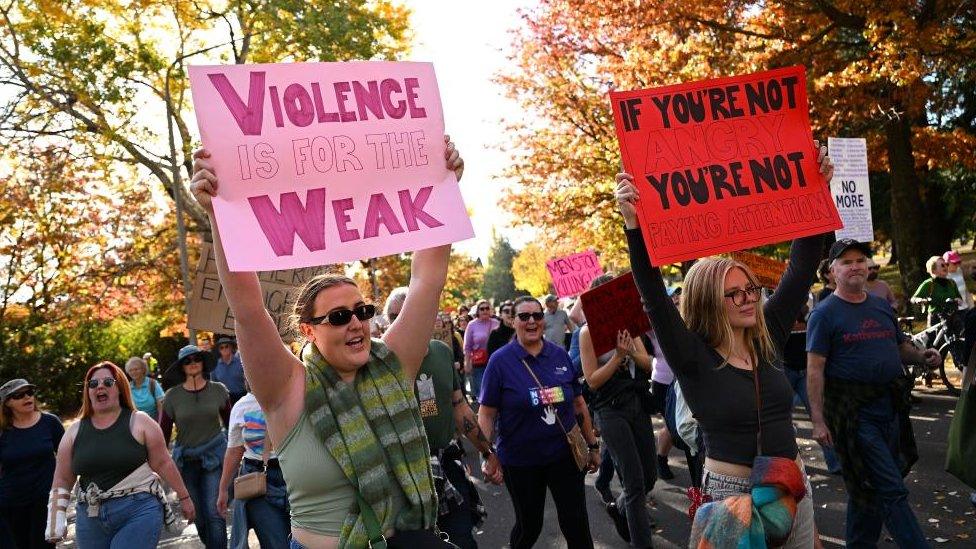

Campaigners calling for an end to violence against women demonstrated in cities around Australia

"So, let's talk about porn," says Ethan West to the classroom of Australian teenagers. Most look slightly awkward. All are uncharacteristically quiet.

"Do any porn videos start off with a relationship where the actors talk about feelings or consent?" he continues. More silence.

At Kellyville High School, north of Sydney, this is just one tricky conversation the 15-year-olds will be having today.

From sexist jokes and coercive control to sexual assault and brutal jealousy-fuelled assaults - there's not much off limits on the Love Bites programme which national charity Napcan has delivered to thousands of students.

The "respectful relationship education" title sounds a little bland. But it is being delivered against a backdrop of violence against women in this country that has been labelled a "national crisis". At its core: trying to shift attitudes and behaviour that has contributed to that culture.

The high-profile stabbing murders of six people at Sydney's Bondi Junction shopping centre last month - in which police said it seemed "obvious" that attacker Joel Cauchi targeted women - brought the issue into sharper focus.

In the month since then, at least three Australian women have been murdered, allegedly by partners or exes.

So far this year, 28 women have been violently killed in Australia, according to campaign group Destroy the Joint which runs the Counting Dead Women project. At the same point last year it was 15.

In 2023, 64 women were killed by someone known to them. In the UK, a country with more than twice the population, the number was 100, according to the Counting Dead Women project in the UK, external.

Two weeks ago, tens of thousands of people around Australia took part in marches calling for gendered violence to be declared a national emergency.

Shriya took part in a workshop at her high school north of Sydney

"For a young woman growing up in Australia it's scary, knowing these things are happening," says student Shriya, who listens intently at the back of the classroom as the group is given small cards with statements such as "equality", "slut-shaming" and "sending unwanted nudes".

They're asked to place the phrases along a line of masking tape on the floor - labelled "respect and consent culture" at one end, and "violence and abuse culture" at the other.

"Think of the line today as a metaphor for your gut feeling," says Tara Gleig, a student support officer who is helping run Love Bites. "Your body will tell you when something's not right. I want you to be able to know where that is."

As a senior constable with New South Wales Police, Ethan West's experience of attending domestic violence calls made him want to fix what he calls an "epidemic".

Working together will make a difference, says Senior Constable Ethan West

"Every two minutes police are called to a domestic violence situation in Australia," he says. And he thinks that for the younger generation, domestic violence is on a "new battlefield".

"Everything's online - there's stalking, harassment. And a lot of the problems with relationships are the sending of intimate images. Young people are sharing nude photos all the time. The relationship may end and they're shared with others. That's a domestic violence offence."

For 16-year-old Kya, who took part in Love Bites a year ago, growing up in Australia leaves her "on edge" - not just the threat of violence but the micro-aggressions of sexist jokes and a feeling she is less valued than the boys in her class and community.

"There are so many new advances in society, but this is still something that's happening," she says. "You have someone making a sexist comment [but] really it's not that difficult to evolve from."

She thinks more boys in her year group need to "step up", though some are clearly committed to doing more.

Izaiah says learning about relationship violence is a "big part of growing up as an Australian teenager"

"As a guy, I feel the need to be more masculine, more strong," says Izaiah - the chattiest of the boys in the session we observe.

"Relationship violence is very serious. Learning about it is a very big part of growing up as an Australian teenager."

Yet change is hard to come by. 10 years ago, Rosie Batty's son Luke was killed by his father, Greg Anderson. Ms Batty went on to become one of the country's top campaigners against family violence, but the national conversation has frequently been reignited by further devastating incidents.

These include the murders of teenagers Jack and Jennifer Edwards, who were shot by their father John Edwards in 2018; the killings of Hannah Clarke and her three young children, whose car was set alight by her estranged husband Rowan Baxter in 2020; and last year's murder of young woman Lilie James by Paul Thijssen, with whom she'd had a fleeting relationship.

So while the recent wave of violence against women has applied pressure on state and federal governments to do more, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese's call for change across all of society is alarmingly familiar.

So too are other concerns. A lack of mental health support, historically inadequate police approaches to domestic violence complaints, and the over-representation of Indigenous Australians as both perpetrators and victims of family violence are just three of the issues which come up again and again.

"At the end of the day, educating young people and this programme going into schools is one piece of a very, very big puzzle," Tara Gleig says. "To be able to make change and [make] that generational culture, societal change, it has to be a collaborative approach."

Under the floodlights of a chilly Australian Rules football pitch In Melbourne's inner suburbs, another community programme is trying to do just that. They want to inject change into perhaps the most traditionally macho slice of Australian society - the sports field.

Matthew Holmes is one of the players enjoying a changing culture at West Brunswick club

"I've played footy since I was a kid," says Matthew Holmes, who at the age of 38 has heard plenty of locker room talk. "I've been at teams where it was very blokey - which in itself was okay - but it did tend to devolve, especially once you got alcohol involved."

He is much happier to be now playing at West Brunswick, a club that has been around for nearly a century but which seven years ago launched a women's team, meeting demand from female players. The change has slowly, and very deliberately, altered the culture there.

New changing rooms are being built to be more inclusive, and they have also brought in some outside help.

"Lots of women and gender-diverse people are wanting to play sport and they're coming into clubs that are traditionally male-dominated," says Dominic Alford of Relationships Australia Victoria, whose Healthy Clubs initiative is trying to tackle gender violence through sport.

"It's a bit of a challenge for those clubs to make the shift to include those people. We talk about respectful relationships and building resilience so they can go out and have those conversations with each other in their sporting clubs but also in their personal life and in their community."

He says the past few weeks of headlines about the high-profile killing of women in Australia has seen a flurry of enquiries from sports clubs and also workplaces.

Kristy de Pelligrini also plays at West Brunswick

It's deeply personal for Kristy de Pelligrini, who remembers her younger days around football clubs. "We played netball and ran the canteen and did all the other jobs around the place. The guys got to play footy and that was it." Now she plays for one of three West Brunswick women's teams.

Teammate Nahkita Wolfe was told at 11 that she had to stop playing Australian Rules football because she was a girl.

"Australian culture and Australian identity is so defined by sport," she says. "It's something that unites us, it's something that brings us together, but yet... for half the population we're often not welcomed into those communities and that's obviously really distressing."

It's a chasm which plays into a much bigger problem.

"You speak to any woman pretty much, we'll be able to tell you about experiences of sexual assault, domestic violence, different things that they've experienced and I'm no exception," says Nahkita.

"A lot of the experiences that I've had have been related to men who have been able to get away with it, because they've always been able to get away with everything because they're good at sport."

Nahkita Wolfe is now playing Australian Rules football again - after being told to stop aged 11

Change has been slow - but there is movement.

"There were definitely some comments that these days you wouldn't walk past anymore - things like 'girls can't play footy' or 'you play like a girl,'" says 26-year-old Conor Fowler, who's been playing Australian Rules football since he was a boy.

"People are [now] asking a question when they might hear something - so what do you mean by that? And just a simple question like that makes people reflect on what they've said."

While this recent wave of violence has made people think about how to fix the problem, those working in the gender violence space say government-funded projects are not a cure-all.

"Money is always important but this is an everyone issue," says Senior Constable West. "If everyone plays their part it doesn't matter how much money is thrown at it - if we're all working at this together we're going to make a difference. No money can fix a problem that not enough people are taking up and championing."

Additional reporting by Simon Atkinson

Related topics

- Published29 April 2024

- Published19 April 2024

- Published31 January 2023