France's immigrant chefs are fighting for legal life

- Published

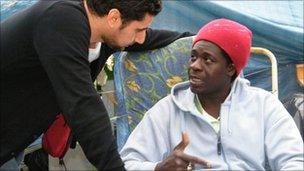

Some unions back the campaign by kitchen staff to be legalised.

The French cherish their culinary tradition and it's a big attraction for foreign visitors to France, the world's most popular tourist destination.

But few tourists realise that these days, many chefs and most kitchen staff in Paris and other big cities are immigrants from Africa and Asia.

Trade unions say a lot of these under-chefs of French cuisine are working illegally in France - but many are paying taxes and social charges.

Despite high unemployment and France's difficulties in integrating immigrant communities, the unions are backing a campaign by illegal immigrant workers to gain the right to live in France legally.

"We're doing the jobs the French don't want," says Diaby Gandega, an illegal immigrant from Mali in west Africa who slipped into France four years ago and works as a dishwasher.

Few Western Europeans are prepared to work long hours in a hot kitchen.

Mr Gandega usually finishes work after the metro and suburban trains have stopped running, so like many other illegal restaurant workers, he has to kill time in an all-night cafe until he can catch a bus home.

He complains that many French people see immigrants as a threat to law and order.

Protest camp

Following clashes with police in mainly immigrant suburbs, President Sarkozy has proposed that foreign-born French nationals be stripped of their citizenship if they commit crimes or are found to be polygamists.

But Mr Gandega says he and many like him are paying into the social security system in France without gaining the rights or benefits enjoyed by other workers.

Many illegal workers pay taxes but have to put up with low pay and have no job security

"We're not hooligans, we're workers. We have jobs and we pay taxes and social charges."

He says illegal workers like him often have to put up with low pay, anti-social hours and no job security.

But with the help of the unions, mainly the left-wing General Confederation of Labour (CGT), they're becoming more organised.

Hundreds of illegal workers march through Paris nearly every week.

Most work in catering or construction and recently they set up a camp in the heart of Paris to press demands to be given residency permits.

Deportations

"We pay into the pension fund and we pay these charges in France, not in our countries," says Mr Gandega. "That's why we're asking for the right to live here legally like other workers."

But France is struggling to integrate millions of immigrants or people of immigrant descent.

Last year the government expelled nearly 30,000 illegal migrants and it has promised to deport more.

But the protests by illegal workers do seem to be having some effect.

Despite tough anti-immigration rhetoric, Immigration Minister Eric Besson has recently announced that the government is taking steps to make it easier for those who have been working in France for years to obtain residency permits.

The head of the youth section of Nicolas Sarkozy's right-wing UMP party, Benjamin Lancar, says it's a misconception that the party is against immigration.

"We are against immigration when immigrants don't work, get some aid from the state, and subsidies from the state, and don't deserve it. That's a problem," Mr Lancar says.

"But when they're working, when they're paying social charges, of course they need to be ever more integrated into our society."

Mr Lancar dismisses accusations by left-wing parties that President Sarkozy is pandering to the far-right by linking crime and immigration.

"We have a very strict policy on immigration and we've closed the camps in Calais where migrants were trying to go to England," he said.

"But France is a very open country and we are choosing our immigration."

Emotional issue

"That means helping those who want to work, who want to succeed in France, who've been working here for a long time, to get residency permits," Mr Lancar said.

But as ever, immigration remains a tough issue for the government, assailed by Jean-Marie Le Pen's National Front for being too soft and criticised by the left for trying to be too tough.

It's become a highly emotional issue.

Many French people feel that their way of life is under threat from the high number of immigrants and what they see as an increasingly assertive Muslim population.

Last year France deported nearly 30,000 illegal immigrants

According to polls, most French support moves to ban the Islamic face veil.

A debate on national identity launched by the government had to be quietly wound down because it generated so much anti-immigrant comment and accusations that immigrants were more likely to commit crimes.

But the South Asian and African immigrants working in France's kitchens are making their presence felt in another way.

These days, more cafes and restaurants are offering dishes like Tandoori chicken or vegetable curries.

One of my local cafes in Paris, whose kitchen staff are all Asian, combines a touch of Oriental spice with the ever more popular American-style hamburger in a "Bollywood burger".

It seems that even la cuisine francaise can no longer resist globalisation.