Q&A: Reform of EU farm policy

- Published

Global warming has fuelled fresh concerns about food security in Europe

The European Union is negotiating a major reform of its Common Agricultural Policy.

The programme is the most expensive scheme in the EU - accounting for more than 40% of its annual budget - and one of the most controversial.

In June 2013 ministers reached a deal with Euro MPs and the European Commission, though the reform package has not yet been agreed in full.

The Commission's original goal was to shift rewards away from intensive farming to more sustainable practices - but environmentalists say that ambition has been watered down. There is also a drive to create more of a "level playing field", to give young people an incentive to get involved in an industry dominated by older farmers and traditional vested interests.

Political parties of all shades, farmers' unions, environmental campaigners and taxpayer groups have all voiced concern about the reforms.

What is the CAP?

Agriculture has been one of the flagship areas of European collaboration since the early days of the European Community.

In negotiations on the creation of a Common Market, France insisted on a system of agricultural subsidies as its price for agreeing to free trade in industrial goods.

The CAP began operating in 1962, with the Community intervening to buy farm output when the market price fell below an agreed target level.

This helped reduce Europe's reliance on imported food but led before long to over-production, and the creation of "mountains" and "lakes" of surplus food and drink.

The Community also taxed imports and, from the 1970s onward, subsidised agricultural exports. These policies have been damaging for foreign farmers, and made Europe's food prices some of the highest in the world.

European leaders were alarmed at the high cost of the CAP as early as 1967, but radical reform began only in the 1990s.

The aim has been to break the link between subsidies and production, to diversify the rural economy and to respond to consumer demands for safe food, and high standards of animal welfare and environmental protection.

How much does it cost?

In 2013 the budget for direct farm payments (subsidies) and rural development - the twin "pillars" of the CAP - is 57.5bn euros (£49bn), out of a total EU budget of 132.8bn euros (that is 43% of the total). Most of the CAP budget is direct payments to farmers.

Regional aid - known as "cohesion" funds - is the next biggest item in the EU budget, getting 47bn euros.

The CAP has been steadily falling as a proportion of the total EU budget for many years. In 1970, when food production was heavily subsidised, it accounted for 87% of the budget.

For the EU's new member states, in Central and Eastern Europe, direct payments to farmers are being phased in gradually.

The eastward enlargement increased the EU's agricultural land by 40% and added seven million farmers to the existing six million.

What reforms to the CAP are proposed?

The proposals include:

Keeping EU farm spending level until 2020, though it may be reduced by inflation. This will disappoint some countries, like the UK, that wanted the CAP scaled back significantly.

The Commission proposed to cap at 300,000 euros the total subsidy a large farm could receive - but that appears unlikely to get into the final deal. The idea was to combat large payments going to aristocratic landowners and wealthy agri-businesses, but it ran up against powerful lobby groups.

Levelling imbalances in payments. Subsidising acreage farmed, rather than production totals, should lead to less intensive farming. Big disparities between high subsidies to farmers in the western EU, and much lower ones to those in the east, should also be levelled out.

Under the reform plan, no member state's farmers should receive less than 65% of the EU average. And the biggest farms would lose up to 30% of their payout - money that would be redistributed to help smaller farms.

Ending sugar production quotas. These are seen to heavily disadvantage competing farmers in poor countries; and they pay huge amounts to giant European agri-businesses.

There has been intense debate about "greening" - the Commission's proposal to make 30% of the direct payment received by farmers dependent on environmental criteria. MEPs and governments insist on flexibility, to allow for the diverse circumstances of Europe's farms.

So these greening targets have been watered down, environmentalists say: the requirement for arable farmers to grow at least three different crops, to promote biodiversity; for farmers to leave 7% of their land fallow, to encourage wildlife; and for farmers to maintain pasture land permanently, rather than ploughing it up.

The definition of an "active farmer" has also been contentious. The current payments system is largely based on land area and past subsidy levels, meaning that landowners like airports and sports clubs, which do not farm, have been getting subsidies based on their grasslands or other eligible land areas.

EU ministers have agreed on a "short mandatory negative list comprising airports, railway services, waterworks, real estate services and permanent sports and recreational grounds".

The two-pillar payments system is likely to stay. Currently direct payments and price support (pillar one) account for more than 70% of the CAP budget, while rural development (pillar two) gets less than a quarter.

On average, pillar one payments provide nearly half of farmers' income in the EU.

Who benefits most from the CAP?

Overall, farmers in the 15 older EU member states benefit much more from the CAP than the newer members.

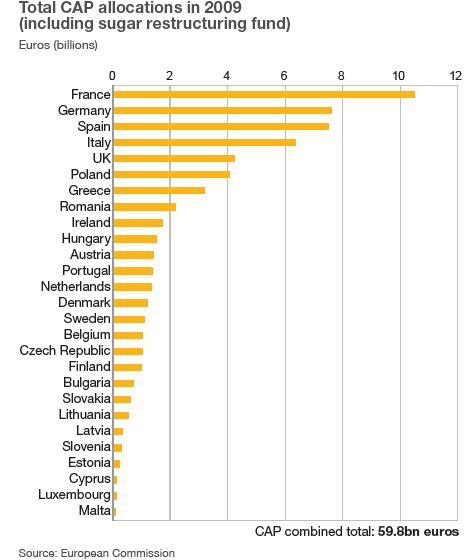

Nationally France benefits most, with about 17% of CAP payments, followed by Spain (13%), then Germany (12%), Italy (10.6%) and the UK (7%).

France is the biggest agricultural producer, accounting for some 18% of EU farm output. Germany comes second, with about 13.4%. Germany is a net contributor to the CAP budget and France will be too in the near future.

The average annual subsidy per farm is about 12,200 euros (£10,374). But payments per hectare range from 527 euros in Greece to just 89 euros in Latvia, because of the transitional arrangements for new member states. The latter are allowed national farm aid to compensate for lower EU subsidies.

CAP subsidies have been blamed for perpetuating inequalities in global food distribution - like the subsidies which protect farmers in other industrialised countries, such as the US and Japan. Combined with import tariffs on food, the subsidies make it harder for developing countries to compete.

Large agri-businesses and big landowners receive more from the CAP than Europe's small farmers who rely on traditional methods and local markets. About 80% of farm aid goes to about a quarter of EU farmers - those with the largest holdings.

Major beneficiaries include rich landowners such as the British royal family and European aristocrats with big inherited estates, according to farmsubsidy.org, a group campaigning for EU transparency.

Has the EU done anything else to reform the CAP before now?

Yes. The EU agreed that milk quotas, which help protect dairy farmers' income, would be phased out. To cushion the blow, the quotas are rising by 1% a year, before they expire in 2015. Yet there have been widespread protests by dairy farmers.

Italy, which overshot its milk quotas, was allowed to implement the full quota increase from 2009.

The EU has scrapped the arable "set-aside" policy - a response to fresh concerns about food security. Farmers had been leaving some land fallow, to prevent surpluses accumulating, but that land will now be put back into production. Conservationists are dismayed, saying set-aside has been very beneficial for wildlife.

A reform of the EU sugar regime was adopted in 2006. The guaranteed price of sugar was cut by 36%, following protests from developing countries seeking to export sugar to the EU.

In international trade negotiations food subsidies are a major sticking point, as farmers are powerful lobbyists in other countries too, and no breakthrough was achieved in the Doha Round global trade talks.

What do the critics say?

One of the biggest criticisms, especially from campaigners against poverty in developing countries, is that the CAP encourages European agri-businesses to export huge quantities of food worldwide that poor farmers cannot compete with on price.

The CAP is seen as part of an unfair trade system rigged in favour of the richer countries.

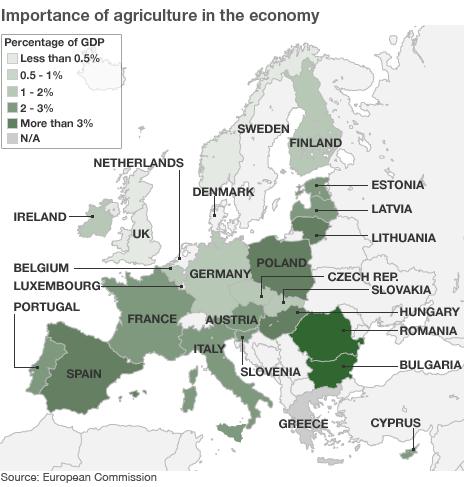

Another widely held view is that Europe is spending far too much on the CAP - when agriculture generates just 1.6% of EU GDP and employs only 5% of EU citizens.

With Europe's economic growth in the doldrums, and fierce competition from emerging giants like China and India, the EU needs to pay less for farming and invest more in scientific research and technology, the CAP critics say.

There is also pressure to spend less on subsidies and more on agricultural research, to improve crop varieties and livestock, which could benefit developing countries.

Even the CAP's supporters agree that there is much room for improvement.

Copa-Cogeca says farmers need to obtain a fair income from the market - they want a "level playing field". Farmers complain that other players in the food chain, such as distributors and commodity speculators, reap the rewards while their income is falling. They want the EU to improve farmers' bargaining power and make market data more transparent.

What do the CAP's supporters say?

If Europe wants to maintain the rich diversity of its rural areas and keep people on the land then it must carry on subsidising farmers, the CAP's defenders say.

Many smallholders work long hours, earning less than the average income, and without the CAP they would go out of business, the argument goes. Their role is vital in safeguarding the character of Europe's countryside - and often picturesque mountain areas are also the most precarious for the rural economy.

The number of people working on farms roughly halved in the 15 older EU member states between 1980 and 2003. About 2% of farmers leave agriculture every year across the EU - and in some countries the figure is higher.

Meanwhile, a growing number of farmers are over 50, so the EU has to provide a financial incentive to attract younger people into farming, CAP supporters say.

Copa-Cogeca warns that cutting subsidies would mean a huge reduction in the number of farmers and an intensification of farming in certain areas. Some fear that agricultural conglomerates and US-style factory farms could change Europe's landscape if the CAP goes.

Europeans demand very high standards of food safety, animal welfare and consumer choice - and that comes at a price, the argument goes.

Globally, CAP supporters say Europe's surpluses can ease food shortages in the developing world.

Food security has become a pressing issue again since food prices soared in recent years. Global warming and overpopulation are increasingly squeezing food resources in many regions.

Europe's post-war achievement of food security is seen as one of the EU's successes - after years of hunger and rationing for many.