Slovenia takes dim view of light pollution

- Published

A special filter shows how much light is escaping from this billboard into the night sky

For many Eastern Europeans a glittering night cityscape is a welcome reminder that the dark days of communism are over.

But for others, night-time light pollution is a menace.

"I am enjoying the economic crisis, because they don't have money for illumination," says campaigner Andrej Mohar, spotting a supermarket clothed in darkness.

Three years ago Slovenia, which broke away from Yugoslavia in 1991, backed Mr Mohar's Dark Sky Slovenia lobby and became the first country to pass a national law to curb rising light levels.

It is still the only country - although in theory 13 Italian regions have implemented similar rules.

Mr Mohar, 48, is an astronomer, and is delighted to be promised a better view of the heavens.

But the move has also pleased a wide range of interest groups, from those demanding energy savings to those concerned about a possible link to cancer and more minor ailments and those worried about falling moth, bat and bird numbers.

Showpiece church

Light allowed to escape even at the horizontal rises into the atmosphere, because of the curvature of the Earth, and can light the sky 200km (120 miles) away.

The fundamental principle of the Slovenian law is that all outdoor lighting must be shaded so that it is kept below the horizontal. Also there are curbs on brightness.

Historic buildings are given special exemption - but even they face restictions.

Dark Sky Slovenia uses a small Franciscan church overlooking Ljubljana as a showpiece of what can be done legally.

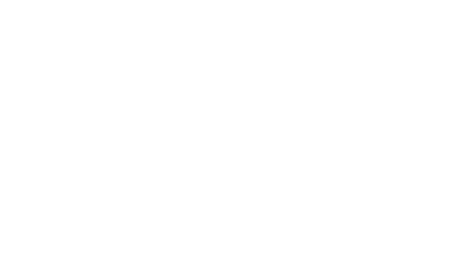

After restrictions are put on street lighting (right), the twinkling glare is much reduced

From a distance it is only a little less spectacular than the scores of other churches that dot Slovenian hilltops at night.

Intricate masks cut in the shape of the church's Baroque outline stop light overshooting into space.

The dimming of the cityscape is not easy to see - or to photograph - because the eye responds to light, not its absence.

But from the hill Mr Mohar points out that on the regulation roads there is not the typical bright daisy-chain of twinkling street lamps, just a ribbon of road and some lampposts to one side.

Driving along one, I notice much less glare.

Such regulation lighting is still far outshone, however, by scores of dazzling roadside billboards, which have so far proved immune from the law.

Some are lit at over 100 times the legal level.

Matej Kobav of trade body the Slovenian Lighting Society, who accepts the need for stricter lighting controls, simply says the billboard lobby is "too strong".

The authorities in charge of policing the light pollution law do not enforce the 12,000-euro (£10,000) fine against the small businesses owning billboards, saying "serious" pollution problems are their priority.

Health threat?

Scientists argue light pollution is serious. It is a group 2A carcinogen, according to Dr Russel Reiter of the University of Texas, although the World Health Organization does not recognise it as such.

The danger is thought to arise because light coming though the eyelids of a sleeping person suppresses the production of melatonin, an antioxidant which protects against cancer.

Vertical light pollution is visible from space

Blue colours present in white light, like that given off by LED lights, are the worst offenders.

Israeli scientist Dr Abraham Haim, of the University of Haifa, agrees that the health effects of light pollution cannot be ignored, having led a study which found that women living in well-lit neighbourhoods were 37% more likely to fall victim to breast cancer than those living in darker neighbourhoods.

Animals suffer ill effects too, in particular birds and moths, often spending nights circling bright lights when they should be feeding, migrating or searching for a mate.

Birds often wheel around brightly lit tall buildings, much as they have been observed to do around oil rigs out to sea.

Mr Kobav welcomes the anti-light pollution laws, not least because they are a boon for the lighting business during otherwise difficult economic times.

But he also complains they are too strict.

"Restricting light emissions to zero degrees makes it is almost impossible to create a nice view of Ljubljana," he says.

A relaxation, he claims, would also mean fewer lights were needed, reducing energy consumption.

The rules have already been relaxed for football stadiums. But further concessions would make the rules far more difficult to police.