Referendum result fails to mask Turkey's divisions

- Published

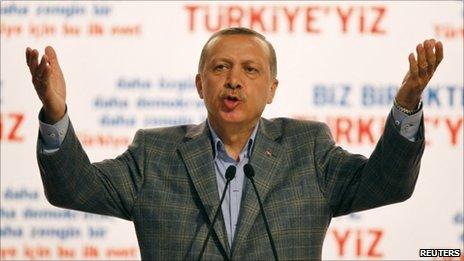

Mr Erdogan hinted that he would build bridges with the opposition after the result

Turkey's Prime Minister, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, described the decisive vote of approval for his constitutional reforms in Sunday's referendum as a "historic milestone".

His party ally, President Abdullah Gul, said Turkey was entering a new era.

The result has also been cautiously welcomed by Turkey's allies in Europe and the United States. But what does it really mean for the people of Turkey?

Most of the 26 amendments make small but important changes to the 1982 charter.

Children's rights are properly defined; personal data and privacy are formally protected; the post of independent ombudsman has been created to mediate disputes between the state and citizens; and the freedom to join unions has been improved for civil servants, although their right to strike is still limited.

Most Turks will not notice the impact of these changes, but they will count whenever people find themselves in conflict with the government.

The changes to the judiciary are more controversial.

Two powerful judicial bodies - the Constitutional Court and the Higher Council of Judges and Prosecutors - are being expanded. The selection of their members is also being changed, giving parliament a slightly bigger say, and the range of professions that can contribute candidates will be broader.

Whether or not this will allow the government to "hijack" the judiciary, as the opposition Republican People's Party (CHP) claimed in its pre-referendum campaign, is a matter of debate among legal scholars.

But the government has not concealed its determination to tame what Mr Erdogan calls a "politicised judiciary".

Nor has it removed the minister of justice from the Higher Council, which hires and fires judges, something the European Union has advocated as essential to give Turkey truly independent judicial appointments.

There is no love lost between Mr Erdogan's Justice and Development Party (AKP) and the rigidly secular ranks of senior judges.

It was the Constitutional Court that came very close to banning the AKP in 2008.

It cannot be a coincidence that this reform package was suddenly presented to the country just days after a big row between the government and the Higher Council over who had the right to dismiss state prosecutors.

Some of the amendments put the military more firmly under civilian supervision. Its personnel can now be more easily tried in civilian courts.

People appeared to vote more on whether or not they trusted the prime minister

But the once-powerful military is already in retreat from playing a political role, and it is hard to imagine it staging another coup in the future.

Perhaps the biggest impact of the referendum will be on the balance of power in Turkish politics.

It has given Mr Erdogan an important symbolic victory, demonstrating after a year in which he chalked up few notable achievements that he is still an unrivalled vote-winner.

The reforms themselves were scarcely discussed before the referendum.

People voted more on whether or not they trusted the prime minister.

A 58% show of support will give Mr Erdogan a boost going into the general election, which has to be held next year.

A third term in office will make him Turkey's most successful politician of modern times.

The referendum offered the CHP an opportunity to raise doubts about the prime minister's leadership and democratic credentials.

For years, the party has been an ineffective opponent of the AKP, confining itself only to blocking government initiatives.

But after an unexpected party coup this year, its veteran leader Deniz Baykal was removed and replaced by Kemal Kilicdaroglu, who has tried to move it beyond simply defending Turkey's secular traditions.

But despite running an energetic campaign, Mr Kilicdaroglu was unable to make a dent in the solid support Mr Erdogan enjoys in provincial towns across the country.

The new CHP leader had to endure the embarrassment of not being able to vote, because of a mix-up over where he could do it.

The CHP is more forward-looking than in the past, but it still looks unlikely to unseat the AKP in the next election.

Kemal Kilicdaroglu has tried to move the CHP beyond simply defending Turkey's secular traditions

Many Turks will now be wondering to what purpose will Mr Erdogan put his referendum victory. Will he try to build bridges with the opposition parties, and end the bitterly divisive atmosphere that prevails today?

In his victory speech on Saturday, Mr Erdogan hinted that he would.

But he is a naturally combative politician, who has betrayed an authoritarian streak on more than one occasion in the past.

During the referendum campaign he appeared to threaten some of Turkey's main business associations, warning that those who refused to take sides over the constitution would be wiped out.

His intolerance of criticism is well known. He rules his party unchallenged.

Mr Erdogan has governed Turkey with a strong parliamentary majority for the past eight years, yet in that time he has not found a way to bridge the gulf of mistrust that divides secular and religious Turks, or those who love and hate him.

His referendum victory has not changed that basic fact of Turkish political life.

- Published12 September 2010

- Published12 September 2010

- Published9 September 2010

- Published11 September 2010