Profile: Yuri Luzhkov

- Published

Mr Luzhkov managed Moscow for nearly two decades as mayor

As mayor of Moscow, Yuri Luzhkov oversaw its impressive transformation after the Soviet period but his leadership style and his power bred resentment.

With his flat cap and tough-talking manner, he had a populist touch which assisted his continual re-election. Equally, his caustic manner and perceived arrogance earned him enemies, particularly among Russians not from the capital.

As the slick new look of the Russian capital emerged, he projected his power into national life and foreign policy, to the extent of sponsoring the personnel and dependents of the Russian Black Sea Fleet in independent Ukraine.

After toying with presidential ambitions in the late 1990s, he allied himself firmly to the party of government, but may have fallen victim to a recent drive by the Kremlin to reassert its control over regional leaders, among whom he was undoubtedly the most powerful.

President Dmitry Medvedev sacked Mr Luzhkov after "losing confidence" in him. Whatever the official reason, his removal has freed up one of the top jobs in modern Russia, with charge of an eye-watering budget and vast property empire.

New city

Yuri Luzhkov was born in 1936, the son of a carpenter who had moved to Moscow from the neighbouring Tver region, according to his biography on the Russian news website lenta.ru.

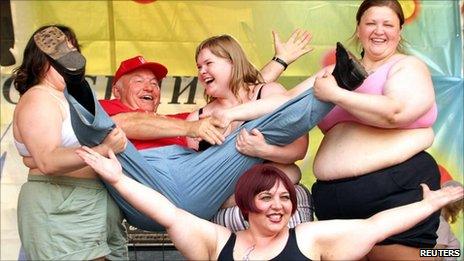

Mr Luzhkov liked to show a jovial face such as when he met Fat Beauty Queen contestants in Moscow in 2005

In the 1950s, he studied at Moscow's Gubkin oil, gas and chemicals institute where he is said to have acquired the nickname Luzhok - not the only one he has been given, with The Cap (Russian: kepka) just as popular.

A career in the Soviet chemicals industry followed, and he engaged in local Communist Party politics in Moscow from the mid-1970s.

He left industry in the late 1980s to work in the Moscow city government, where he eventually headed the commission on co-operatives, as the USSR was experimenting with private enterprise.

His guiding principle in that post is said to have been "what is not forbidden is allowed".

In 1991, he was elected deputy mayor under pro-democracy politician Gavriil Popov, in the city's first direct mayoral ballot.

When Mr Popov resigned the following year, Mr Luzhkov was appointed mayor by President Boris Yeltsin.

His popularity in the post became indisputable. In 1996 he took 95% of the vote in this city of 10.5 million people, and he won just under 70% in 1999. In 2003 - the last direct election the city held - he won 75%.

New city of steel and glass: Moscow's Swissotel Krasnye Holmy by night

Muscovites associated Mr Luzhkov with high investment, low unemployment and the facelift of their city, watching as the crumbling infrastructure of late Soviet times was replaced by new buildings, new roads, new projects.

His hobby of keeping bees seemed appropriate for the manager of a metropolis buzzing with new life, and his passion for football struck a chord with Moscow's male population.

While the new Moscow City financial district symbolised Mayor Luzhkov's vision of the city as a world business centre, he polished his religious and patriotic credentials with the reconstruction of Christ the Saviour cathedral, destroyed under Stalin, and the renewal of the Moscow Victory Park complex commemorating World War II.

But detractors despised much of the new architecture, and public sculptures such as the giant Peter the Great monument on the River Moscow attracted ridicule.

Historic features of the city were demolished, too, such as the art nouveau Voentorg department store, while plans to build a motorway through the city's Khimki Forest sparked a bitter row.

And for all Moscow's ambitions to rival New York or London, it remained socially a deeply conservative city. Mayor Luzhkov became known for his opposition to parades by gay rights activists seeking to celebrate their new-found civil liberties in post-Soviet Russia.

Powerful couple

Presiding over an annual budget said to reach $40bn, Mr Luzhkov wielded enormous financial power and critics have sought to tie this to the personal fortune of his wife, Yelena Baturina.

Mr Luzhkov is married to Russia's richest woman

Forbes magazine put her fortune at $4.2bn in 2008. If this has since fallen to just below $3bn, the property developer is still Russia's richest woman.

Mrs Baturina insisted her fortune was down to her own business dealings and unrelated to her husband's post.

The powerful couple were well-known for going to court to protect their reputation, and threatened to sue state-run TV channels when they began what appeared to be a co-ordinated campaign to discredit Mr Luzhkov in the weeks before his sacking.

This TV campaign was the writing on the wall for Moscow's mayor, but his dismissal still came as a shock to some.

Yuri Luzhkov had not challenged the Kremlin in more than a decade, not since it had become clear that the Yeltsin era was to be succeeded by that of Vladimir Putin and his proteges, Mr Medevdev among them.

As president, Mr Putin had endorsed Mr Luzhkov for his fifth and final term in office as mayor, in 2007.

Mayor Luzhkov's support for Ukraine's ethnic Russians, which earned him a travel ban from Kiev, appeared to complement the Russian government's own policies.

Some suggest the mayor's handling of this summer's forest fire crisis, when he did not rush back from holiday, antagonised Mr Putin, who as prime minister stayed on in the heat and smog of Moscow, only venturing out to visit fire victims around the country.

Others point to a newspaper article in which Mr Luzhkov referred to a "heavy atmosphere" in society, for which President Medvedev effectively slapped him down.

Perhaps the mayor's age - he turned 74 just before his sacking - went against him in the eyes of Mr Medvedev, 45, and Mr Putin, 57.

What is clear is that the Kremlin, not the people of Moscow, will pick the next mayor.