Villagers despair in Hungary's red wasteland

- Published

Villagers from Kolontar say they doubt whether they will ever be able to go back home

Hungarians displaced by the toxic sludge that flooded a rural valley are beginning to wonder whether they will ever go home, says the BBC's Nick Thorpe in Ajka.

The Sports Hall in Ajka contains several hundred beds, set up when the evacuation of Kolontar was announced, early on Saturday morning.

But only a handful are occupied - mainly by the elderly, and the poorest families.

"We feel like animals in a zoo," one tells the village priest, Miklos Mold, who is a frequent visitor at the hall.

He gently explains to them that the reporters are only doing their job, even as he tries to explain to the journalists that they should keep a respectful distance from the mourners, as the funerals for the eight victims of the disaster begin on Thursday.

As if on cue, a woman of about 60, wearing a head scarf, rushes up with a basket of freshly baked cheese scones, to offer to the journalists outside the hall.

We try to persuade her to take them to the displaced people instead.

But she insists, weaving a path among Japanese cameramen in protective suits, Spanish television journalists, French soundmen and Austrian satellite engineers.

"I baked them myself," she tells each, proudly, in Hungarian. "They are still warm."

"They said we can go back in three days," said one Kolontar villager, Peter Molnar, "but maybe we can never go back."

His village now swarms with labourers, their blue overalls spattered with red mud, with soldiers and volunteers taking part in the relief effort.

"No returns to Kolontar before Friday, at the earliest," says Tibor Dobson, of the Disaster Management Unit.

Dangerous dust

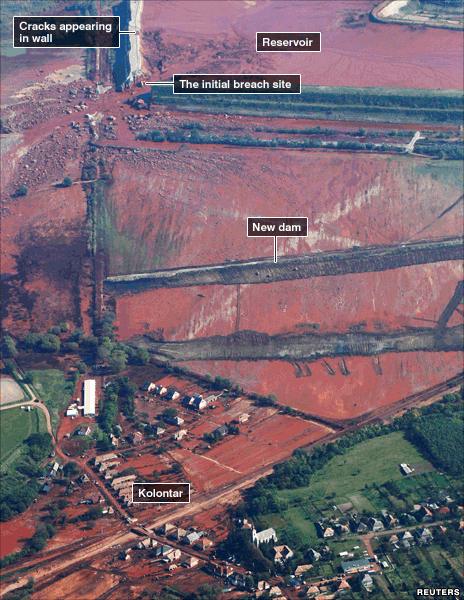

In the fields around Kolontar, 1,200 men labour with heavy machinery - 300 diggers and bulldozers and trucks - to build the new protective barrier.

A criminal investigation into the company is trying to establish whether it overfilled the reservoir

It is nearly finished, and will have three interlocking sections - to defend the remains of the village, the railway line, and most importantly now, the town of Devecser, further down the valley.

One wall reaches the village church. An official compares the task to building a new section of motorway - in three days.

One day, the designers of the barrier say, a bicycle path might even run along the top. For now, the workers labour in a cloud of red dust, stirred up by the earth-moving equipment.

"The dust is the real enemy now," says the mayor of the nearby town of Devecser, Tamas Toldi.

Measurements in the town on Monday showed levels of the dust in the air were three times the maximum safety level.

On Sunday, the priest Miklos Mold mentioned Moses in his sermon, parting the Red Sea to take his people to the promised land.

The congregation were a strange mix, of townspeople in their Sunday best, and relief workers looking like astronauts in their white protective clothing.

The church itself stands yellow and white in the midst of this red-stained town. So much is red in the surroundings, that the eye takes unexpected pleasure in anything that is not red - the gold paint on the inside of the church, the deep blue of Mary's cloak, as she holds the crucified body of Jesus in her arms.

Jobs at risk

"I had a good week..." said seven-year-old Noel, as his grandmother re-arranged his face mask as he came out of the church.

"I played with my friends instead of going to school. But we had to play inside..." He has a single bag with his clothes packed, ready to go.

In Ajka, home to the aluminium plant, 3,000 jobs depend directly on the company.

The managing director, Zoltan Bakonyi, was taken in for questioning by police on Monday, and the government announced that a new, caretaker management will be appointed.

The criminal investigation into the company is trying to establish whether the company overfilled the reservoir, in breach of regulations, and whether the management knew of a structural weakness, and did nothing.

In a restaurant in the same town, 11 burly men in leather jackets and extensive tattoos on their arms take over a long table in the corner.

It is the Four Rivers Chapter of a motor bike club, who have come to offer their help to the relief effort. With the help of local bikers, they aim to identify families bereaved by the disaster, and collect money for them.

Some of the rivers named in their club title, proclaimed on their jackets, have been polluted by red sludge.

"We can't do much," said one of them, Tom, "but we can do something."

- Published11 October 2010

- Published8 October 2010

- Published8 October 2010

- Published10 October 2010

- Published9 October 2010

- Published8 October 2010

- Published6 October 2010

- Published7 October 2010