France divided over Goncourt winner Michel Houellebecq

- Published

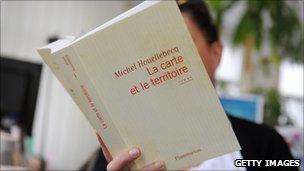

The Prix Goncourt brought the reclusive Houellebecq into the limelight

So what kind of man is Michel Houellebecq, this year's winner of France's top book award the Prix Goncourt?

Here are some of the few things we know for sure.

He has by far the widest international following of any modern French author.

He has written five novels since 1994, all of which have been translated into dozens of languages.

His theme is the spiritual loneliness of the modern European, confronted by consumerism, the corporate work ethic and a civilisation in decline.

Yet he is by no means a political writer. Indeed his biggest critics are on the political left, who say he is a reactionary.

He lives in the Irish Republic, smokes a lot, and is something of a recluse.

To go any deeper into the man, the only solution is to turn to the books. And a particular source of information is in fact his latest, the Goncourt-winning La Carte et le Territoire [The Map and the Territory].

'Houellebecqian'

This is because La Carte et le Territoire contains not one, but two characters who are clearly based on Houellebecq himself. One of these is actually a writer called Michel Houellebecq, who lives in the Irish Republic - and ends up being murdered.

The other is the novel's hero, artist Jed Martin, conditioned equally by a sense of disorientation and detachment from the world around. In the words of one critic, if Martin is "not Houellebecq himself, he is certainly Houellebecqian".

To quote from the book: "His [Martin's] outlook on the society of his time was more an ethnologist's than that of a political commentator".

Like Houellebecq, Martin's indifference to news and current affairs is matched by a compulsive interest in consumer goods.

At one point, the fictional Houellebecq tells Martin that in his "life as a consumer" he has known only three "perfect products": a pair of Paraboot shoes; a Canon computer-printer hybrid; and a "Camel Legend" parka coat.

'I loved these products, passionately. I could have spent life with them, re-buying them regularly as they wore out," he says.

In La Carte et le Territoire, we also get a glimpse of Houellebecq's ramshackle cottage near the River Shannon, a Lexus SUV, and an overgrown garden.

We are told he suffers from eczema and looks like an "old, sick tortoise"; loves charcuterie [cooked pork] and red wine; hates journalists and sunlight.

"It's true," the fictional Houellebecq says, "I derive only the feeblest sense of solidarity with the rest of the human species."

It is a fact that the real-life Houellebecq rarely appears without his beloved parka - but are the misanthropy and consumer-obsession genuine parts of his character? Or are they feigned for artistic purposes? Only his friends know for sure.

Poisonous

Houellebecq's childhood certainly predisposed him to a life at one remove from the rest of us.

Houellebecq's critics say he is a product of 21st-Century consumerism

He was born Michel Thomas in 1956 on the island of La Reunion to parents who left him six years later to indulge in a round-Africa road trip. As a result he was brought up by his maternal grandmother, whose name he took for himself.

His relationship with his mother, now in her 80s, is poisonous. In his 1998 book Les Particules Elementaires [Atomised], he portrayed her as a self-centred hippy, and in return she branded him an "evil stupid little bastard".

After studies in agronomy, Houellebecq had various unimportant jobs before establishing himself on the literary scene in 1994 with Extension du Domaine de la Lutte, published in English under the title Whatever.

His two later books are the 2001 Plateforme, which dealt with sex tourism, and La Possibilite d'une Ile [The possibility of an island] in 2005, about the Raelian cult.

Enemies said he revelled in semi-pornography, and that he was not an observer of 21st-Century consumerism: he was its product.

They also railed at his comments on Islam, which he described as "the most idiotic religion of them all". The phrase landed him in court on a charge of racial hatred, but he was cleared.

Houellebecq has twice before been in the running for the Goncourt. On each occasion - in 1998 and 2005 - his opponents outnumbered his supporters.

Unique style

Today there are still many who see him as an impostor, a second-rate writer who has cleverly engineered his transformation from the enfant terrible of French literature to its favourite son.

According to literary critic Pierre Assouline: "With great skill and a certain marketing-style cynicism, Michel Houellebecq created a manufactured product which the Goncourt committee could not refuse."

However overriding opinion is that the recognition is long overdue.

It is not just that Houellebecq is France's best-known serious novelist - he also writes in a way which sets him miles apart from his rivals.

Much French writing suffers from an aesthetic and intellectual preciousness, which turns off ordinary readers and certainly makes books difficult to sell abroad. It also evokes a France that exists purely in the literary mind.

Houellebecq on the other hand writes about a France that is as instantly recognisable as it is depressing: a France of supermarkets and shopping malls, soulless provincial towns, brands, television, budget airlines, second-rate celebrities.

His language is also conversational and direct. Some say that shows he lacks true "style" - but if so, it matters little.

According to Christophe Barbier, editor of L'Express magazine, Houellebecq should be celebrated not so much for his form as for his content.

"He is indeed a great writer, a great sociologist, a great interpreter of what we are today: us as France, us as Europe, us as the West," said Barbier.

"He depicts us on our path of decline; our twilight; the downward slope of our civilisation."

- Published8 November 2010