France braced for diabetic drug scandal report

- Published

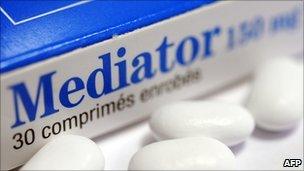

Mediator was first developed in 1976 to reduce fat levels in the blood

France is gearing up for a report on one of the country's biggest medical scandals of recent years. French health experts now believe that the drug known as Mediator, developed for treating overweight diabetics, could have killed between 500 and 2,000 people before it was finally banned.

Mediator stayed on the market despite a succession of warnings over its side-effects, which include heart valve disease and pulmonary hypertension.

It was also hugely misprescribed, with doctors routinely handing out Mediator as an appetite-suppressant for people with common or garden weight problems.

Last week a judicial investigation was launched to establish any criminal responsibility in the affair. Scores of victims have filed suit, and on Saturday the government's Social Affairs Inspectorate will deliver its findings about what went wrong.

The questions that need answering are many.

Why did it take so long for France's regulatory agencies to respond to the warning signs over Mediator?

What was the role of the drug's manufacturer, the French pharmaceutical company Servier, whose 88-year-old boss Jacques Servier has close links to politicians including President Nicolas Sarkozy?

Is there a proper separation of powers between the different groups of people who develop, test, authorise, market and monitor new drugs? Or do conflicts of interest prevent objectivity?

How many other drugs are there being prescribed, with little benefit and some potential danger to users? And how much money are these treatments draining from the already hard-pressed health budget?

General treatment

For a country that likes to think it has the best medical system in the world, the Mediator affair is both an embarrassment and wake-up call. Whoever is at fault, there is general agreement things cannot go on as they are.

Based on a molecule called benfluorex, Mediator was first developed by Servier in 1976 as a lipopenic - a drug to lower fat levels in the blood. Later it was prescribed to diabetics to help them lose weight.

But then, as its appetite-suppressant properties were recognised, family doctors began offering Mediator as a general treatment. Anyone worried about putting on the pounds could be offered a course of the drug - even though legally it was authorised for diabetics alone.

By the time it was taken off the market in November 2009, it is reckoned that some five million people had taken Mediator, making it among the 50 most-prescribed drugs in the country. More than 80 million boxes were sold over its last 10 years, at a cost of 423m euros ($550m) to the national health insurance fund (CNAM).

Importantly, users were reimbursed by the CNAM for 65% of the cost of the drug, because right to the end it was declared to be not just safe but effective.

And yet from the mid-1990s alarm bells should have been ringing.

In 1997 a drug based on the same molecule called Isomeride was abruptly taken off the market because of revelations about its side-effects. The US banned Mediator on the grounds that it presented the same risks as Isomeride, but France failed to follow suit.

Personal research

From 1999 cases of heart valve disease began to be reported, and other countries such as Switzerland and Spain banned Mediator.

In France a committee advised that the health benefits of the drug were negligible, and so recommended that it should no longer be reimbursed by the CNAM.

But the committee made no mention of risks - and in any case the powers-that-be simply ignored its advice. Mediator continued to be reimbursed at 65%.

Finally a pneumonologist from Brittany called Irene Frachon followed up a hunch and conducted intensive personal research, drawing on medical records from across the country.

Her findings - of a clear pattern of heart valve problems among Mediator users - prompted more studies that led to the ban in November 2009.

Since then, two more studies have been released. One concludes that 500 deaths could be linked to Mediator between 1976 and 2009. The second, broader, study puts the figure at 2,000.

These numbers are disputed by Servier, which says there are only three documented cases where death can be clearly attributed to Mediator. In other cases, it says, aggravating factors were at work.

Servier's head of external relations Lucy Vincent said in a weekend newspaper interview: "We do not deny that Mediator may have been a real risk for certain parties. If it caused the deaths of three people, that is already too many."

Critics say part of the problem lies in the complexity of the French regulatory system, with no clear boundaries between a number of competing agencies.

But some go further, accusing Servier of using a network of influence to avoid unwelcome inquiries into its money-spinning drug.

"Servier has shown an extraordinary capacity for escaping criticism," said Socialist deputy Gerard Bapt, a cardiologist who has taken a close interest in the scandal.

"The main reason is because it has been able to infiltrate all the relevant scientific committees working on this drug."

For Irene Frachon, "the conflicts of interest are palpable… Among the medical establishment, in the pharmaceutical and cardiological communities, there are people close [to the Servier laboratories]."

'No usefulness'

France's second largest pharmaceutical company is still run by the man who founded it more than 50 years ago. Jacques Servier is an austere figure who rules his empire with an autocrat's attention to detail.

Industry-watchers say that over the years he has funded numerous medical foundations and research fellowships. He has also cultivated politicians of all stripes - not least of them Nicolas Sarkozy, whose political fief of Neuilly-sur-Seine is home to Servier's headquarters.

Twenty-five years ago Servier was one of the first clients to the young Sarkozy's new legal practice, and in 2009 the president decorated Servier with the Grand Cross of the Légion d'honneur.

Critics of the French system say the regulatory authorities are so in thrall to drug-manufacturers like Servier, especially if they are French, that they find it almost impossible to withdraw treatments from the market.

"We have flooded the market without [sic] about 800 products - probably twice that if you ask me - which have absolutely no usefulness at all for the consumer," said Professor Philippe Even, president of the respected Necker Institute.

"They eat up half of our health budget solely for the benefit of shareholders in pharmaceutical companies and with no positive effects at all for the sick."

For Bruno Toussaint, editor of the independent medical magazine Prescrire, "About three-quarters of the drugs on the market have little or no health benefit and are utterly redundant."

"Mediator is not an isolated instance," he said.

"It is the affair which blows the lid on an entire system."