Churches reach out to Hungary's struggling Roma

- Published

Hungary's new centre-right government has allied itself with the churches in a drive to create jobs and pull Roma (Gypsy) communities out of poverty.

The BBC's Nick Thorpe reports that social work by the churches is already helping to improve the lives of Roma in eastern Hungary.

"One good Gypsy," said the shopkeeper in Gaborjan, "doesn't mean they're all good".

Jozsef Toth - a good one - smiles and nods. He is a rare bird - an ethnic Roma priest serving a non-Roma congregation. It has not been an easy road so far, but he has made progress.

Fr Toth has seen Roma attendance at his religious education classes grow

In the village shop the shelves are stacked with goods that the poorer families - Roma and non-Roma alike - can rarely afford.

Break-in attempts are regular, but their success rate has fallen since CCTV cameras were installed outside.

The shop gives credit to most people in this poor village of 2,000, some 500 of them Roma. Only those who fail to pay back what they owe are shunned.

Overcoming suspicion

"When I finished my studies, and started looking for my first job as a priest, there were congregations who turned me down immediately," Jozsef Toth says.

But he persevered, and his bishop sent him to Gaborjan for a trial period. Here too there was hostility at first. But when they saw him help dig a new sewage ditch and heard him preach, the opposition softened.

"It was wonderful. We went from house to house with a wheelbarrow, and some people gave us firewood, others coal, so we didn't freeze that first winter."

He takes me into his 17th-Century church, to marvel at the painted wooden panelling. He is sad that the local Roma rarely come to church.

But the children flock to his voluntary religious education classes. At the local primary school, the number has risen from just four, when he arrived here 16 years ago, to 60 or 70 today. His own children sit proudly in the first row.

Ambitious renewal plan

The Hungarian government is due to sign a deal with the main churches to allow them to apply for state funding for educational, social and labour programmes. So for the first time, the churches can get involved in job creation.

Hungary's 800,000 Roma - many of them destitute - are a priority. The government wants to get a million Hungarians back to work in the next 10 years - 200,000 to 300,000 of them Roma.

In Kekcse the Roma faithful flock to a humble front room for prayers and songs

Jozsef welcomes the programme, but worries whether congregations like his will ever be able to participate.

"There was a European Union project we wanted to apply for," he explains, "but you had to match the funds available with some of your own".

"Not so long ago, our electricity was cut because we couldn't pay the bill. This parish just doesn't have $2,000 to spare."

Hungary's State Secretary for Social Inclusion, Zoltan Balog, is himself a Protestant pastor. "It will be the job of the churches to go to the communities with their own proposals," he says.

Further east, in the little village of Kekcse, Elek Balogh holds morning prayers in the front room of his house.

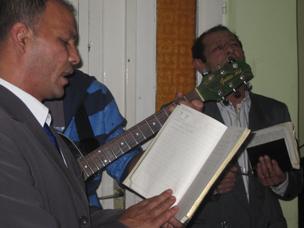

The Roma hymn-singing in Kekcse is far removed from traditional Gypsy music

The room is packed with Roma, young and old, women and men, to sing and pray together.

Two men play electric guitars, and the hymns sound closer to negro spirituals than traditional Gypsy music.

Abstinence campaign

"A glass of wine or beer in moderation does little harm," says Mr Balogh. But several women disagree. "Neither I nor any of the men in my family drink any more," says one woman proudly.

Others agree that the village bar used to be 90% Roma, but now only one in 10 men goes there.

Their faith has also helped many Roma give up another habit which used to swallow their meagre resources - gaming machines.

The only dispute left concerns tobacco. Leaders of the Hungarian Baptist Church, to which they belonged, were in Kekcse last year with some of the American brethren, and suggested that two local pastors be suspended from their jobs, because of their addiction to smoking. That was a step too far - the church broke away from the Baptists and is now independent.

The Greek Catholic Church faces rivals for Roma hearts in Hodasz

At the end of the village, Janos Fekete shows me round the shack where he lives with his five children and grandchildren. The little girls are barefoot and wide-eyed, a woodburning stove throws out a good heat, and dogs compete with the children for space beside it. But the door is broken and a freak storm last year severely damaged the roof.

"I know a better home is waiting for us in Heaven," explains Mr Fekete, also a Baptist, "but it would be nice if our house on Earth was in slightly better condition".

Choice of churches

Not far away in Hodasz, 70 years of the Greek Catholic Church's mission to the Roma has borne many fruits: a Roma church where the liturgy is sung in the Romany language, with guitar and synthesizer accompaniment; a kindergarten; a home for the elderly, and another upstairs for battered women and their children.

Fr Toth says progress is being made despite anti-Roma prejudice

Father Miklos Soja, who worked in the parish from 1941 to 1986 laid the foundations. Forty local people, most of them Roma, are employed in the three institutions.

"Hodasz could easily be a model for the whole country," says Fr Gabor Gelsei, the senior priest.

There is rivalry between the Greek Catholics and the Faith Church, a new Protestant church which, like the Pentecostalists, has swept through Hungary - especially Roma communities.

But Zoltan Balog, the state secretary in Budapest, says the Faith Church "could be our partners" too.

"If a civic or religious organisation helps these Roma people to leave their bad situation and live better, that is the main thing."

The Faith Church alone claims to have 100 Roma pastors in Hungary.

The more established churches have the advantage of offering services for communion, baptism and funerals. But many Roma seem to prefer the down-to-earth, speaking-in-tongues, healing atmosphere of the Faith Church prayer rooms.

Back in Gaborjan, Jozsef Toth admits that there is a problem with theft by Roma. An elderly couple lost 11 of their 12 hens over Christmas. And a church in a neighbouring village was broken into over the new year, and money and precious objects were taken - later recovered with the help of a police dog.

"The culprits are usually identified," he says, but adds that it is unfair to blame the Roma collectively.

"When they see me coming, there are still those who say 'there goes the Gypsy priest', instead of 'there goes Jozsef Toth'."

- Published17 January 2011

- Published10 November 2010