Azerbaijan cracks down hard on protests

- Published

Police tolerate no dissent - even a child who shouted "freedom" is taken away

In oil-rich Azerbaijan, opposition supporters inspired by revolutions in the Arab world are taking to the streets and calling for a change of government.

The authorities, however, will do everything it takes to hang on to power.

It is a peaceful Sunday afternoon in Baku's immaculately restored city centre. In a central square next to the ruling party's headquarters, hundreds of people stroll around the 19th Century fountain or chat with friends.

But all these people have come here for a reason.

The young men in jeans, trying to look unobtrusive as they smoke cigarettes, are about to launch a protest against alleged government corruption.

Meanwhile, the crackle of walkie-talkies from business-suit pockets blows the cover of plain-clothed security officers ready to pounce.

Just before the demonstration is due to start, dozens of police officers in riot uniforms troop in from all sides and quickly form a cordon around the square.

Suddenly a man shouts something. Instantly, he is lifted off the ground by four policemen. They carry him to a waiting van and throw him in.

A crowd of officers then surrounds a young woman who is holding hands with a little girl aged about six.

The child shouts out "freedom" and punches one tiny fist into the air. She is grabbed by police, starts to cry, and is pushed with the woman into a police car.

Riot police poured into the square in Baku just before the protest began

The woman then shouts out in Azeri and I ask a local reporter to translate for me. "We don't have money to buy medicine," is the answer.

"Don't think you'll be able to keep your government," the woman adds, turning to the policeman who has hold of her arm. "A 30-year-old government collapsed in Egypt."

In total 65 people were detained last Sunday. All were arrested either on their way to the protest, or as soon as they shouted out anything criticising the government.

Rasul Jafarov, a lawyer with the human rights organisation "Institute for Reporters' Freedom and Safety", says the revolutions in the Arab world are now inspiring people here to take to the streets.

"For the past five years the situation was very bad when it comes to guaranteeing human rights and freedoms," he said.

"People just waited and waited and waited. But because of events in the Arab world, people here now understand that they should go and ask the government to meet their demands. Now people realise they have a real chance of changing something."

Hundreds detained

But the authorities have also been taking note of events in Egypt and Tunisia. They want to pre-empt unrest before it happens and have said no demonstrations will be tolerated in the city centre. They have stuck to their word.

So far, hundreds of people have been detained before or during three demonstrations since mid-March. Youth activists have also been arrested in their homes after trying to organise protests on Facebook, and are now in pre-trial detention.

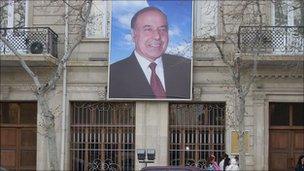

The Aliyev family may be heading for a third decade in power in Azerbaijan

Amnesty International defines seven of the detainees as prisoners of conscience, and has called for their immediate release.

Reactions like these are nothing new. In 2009 two youth activists were sent to prison for two years after they posted a satirical video on YouTube, sending up the government by showing a donkey giving a news conference.

But human right activists say that since the Arab revolutions, the government has started reacting even more aggressively to criticism.

When you walk around central Baku it is hard not to be impressed by the meticulously renovated 19th Century buildings and the innovative architecture springing up all over the city.

But although oil has brought strong economic growth, that wealth remains in the hands of the few. Leave the city, and many people don't even have electricity or running water.

The oil wealth has also pushed up prices, meaning that the cost of living here is now comparable to cities in Western Europe. But the average wage is less than $400 (£245) a month.

In an attempt to stave off unrest, the government has recently launched a high-profile anti-corruption campaign.

The West would certainly like to believe President Ilham Aliyev's claims of democratic freedom.

Azerbaijan has vast oil and gas reserves, and its business-friendly secular government is seen as an important bulwark against neighbouring Iran. Because of its location the country is also a key stopover for Western troops and supplies bound for Afghanistan.

'Democratic elections'

According to parliamentarian Mubariz Gourbanli, a member of the leading party, the West has nothing to worry about.

"We are not an Arabic country, we are a European country," he said.

"We have democratic elections. But this square in the centre of the city just isn't a place for protests. They can protest but only in certain areas. That's the law and we have to stick to that."

However, these areas are in remote locations which protesters cannot get to.

Political analyst Arastun Orujlu disagrees that there is true democracy here. He says the new anti-corruption measures are cosmetic and show that the Azeri government feels threatened.

"The Azeri government understands that we have the same system here as they had in Tunisia or Egypt. It is completely the same - just imitations of rights, imitations of freedoms, imitations of free economy and imitations of a market economy. In fact it is a totally corrupt government."

That is something these protesters want to change. But they are in the minority.

President Aliyev's family has ruled with an iron grip since 1993.

The media is tightly controlled by the state and almost 80% of the population either never use the internet or do not know what it is.

So, given that most people in Azerbaijan are probably not aware that protests have even taken place, the Aliyev family could soon be looking at a third decade in power.

- Published18 November 2010