Tunisia migrants in Italy set sights on France

- Published

Ventimiglia is the departure point for many migrants bound for France

On his front - so no one can steal from it - Walid wears a backpack. It contains everything he brought with him from Tunisia.

On his face, he wears a pained expression. "The French," he explains calmly, "are racist."

"My grandfather fought for France in the First World War, and in the Second. Now they don't want me in their country!"

They most certainly do not. Since the Arab uprisings began in January, some 25,000 people - mostly Tunisians - are estimated to have made the short but often perilous trip across the Mediterranean to Europe, and the start of what they hope will be a new, prosperous life.

Italy says it has been overwhelmed by the influx, and it has sought to encourage other EU states to take some of the illegal arrivals.

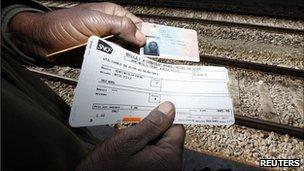

It has granted thousands of temporary permits allowing them to stay. Armed with these, many Tunisians have chosen to head for a country where they have family and friends - France.

Invisible border

It is an issue that is threatening to undermine one of the most cherished elements of the modern European Union - a Europe without borders.

It is hard to know exactly where the frontier between France and Italy actually is these days. Travel on the short train ride between the northern Italian town of Ventimiglia and the French city of Nice, and there is no sign, no flag, certainly no immigration check.

They were removed under the Schengen agreement, an accord that allows travel within 25 European states without border controls.

It is a system perfect for tourists, businesses and, it turns out, illegal immigrants.

Bassem says he left Tunisia looking for work

It is why the train station in Ventimiglia has been packed recently with apprehensive-looking north Africans, clutching tickets, staring at departure boards.

As the 1117 to Cannes pulls alongside platform three, the men shuffle towards the opening doors, not quite sure if is really going to be so easy.

They get on board, find some space and slouch down low into their seats. Then the train sets off, soothingly quiet, not at a clatter.

Several tunnels and several stretches of sparkling coastline later, and they are in France.

One of them is Bassem, who insists he is 18 - though he looks younger. From behind Ray-Ban-style mirrored shades he grins: "France is beautiful!"

He has come, like so many, for a job. "There's much unemployment in Tunisia," he mutters.

Unwelcome

The French authorities have been beefing up security along the route in recent weeks. They have sent some of those making the trip back to Italy. France insists this is still within the spirit of the Schengen agreement.

On Bassem's train, though, the police do not turn up.

At Nice station the Tunisians stand for a moment, wondering what to do. Then they set off down the platform, mixing with travellers and commuters, into the arrivals hall and out of the station.

One by one they head into town. One turns back and flashes a victory sign. Then he, too, is gone.

This is not what Eric Ciotti wants. He is the president of the region, and a prominent member of French President Nicola Sarkozy's ruling party.

"The illegal immigrants who have arrived in Italy must be sent back to Tunisia. That is Italy's role," he says.

"I'm against Italy's decision to give them temporary permits so they can come to France. [Italy] simply want[s] to export the problem to France."

Is it racism that drives him? No, he says. "There are plenty of immigrants living in France [who] apply for visas and come here legally."

But the arrivals from Tunisia, he insists, must be sent back.

Italy has been issuing documents allowing migrants onward passage to the rest of Europe

Back down the train tracks, in the newsagent at Ventimiglia railway station, the owner, Antonello, says his country needs help.

"This has been seen as an Italian problem. I believe it is a problem for the EU. We need to co-ordinate [with other countries]" he says.

There is talk of re-working the Schengen agreement to allow more scope for countries like France to patrol the border. There is talk also of help for Italy.

The problem, though, will not go away. There is a worry that as the fighting continues in Libya, many more will try to cross the Mediterranean to Europe.

And those already in Italy are still intent on exploiting the Europe without borders.

Outside Ventimiglia's police station - peering through what you might call the new doorway to Europe - a group of north Africans wait to hear if they have been granted temporary permission to stay. Most seem to get it.

When they do, some will remain in Italy. Most talk of heading to France, Belgium, Germany. One asks if it is easy to get to Britain.

All have the same European Dream - a new life, a job, settling down with a woman (they are all men here today), a family.

Most know that some in Europe see them as lazy criminals stealing jobs from others. It does not put them off.

- Published24 April 2016