Schengen: Controversial EU free movement deal explained

- Published

Laurence Peter looks at what the end of the Schengen zone could mean

The Schengen Agreement abolished many of the EU's internal borders, enabling passport-free movement across most of the bloc.

It take its name from the town of Schengen in Luxembourg, where the agreement was signed in 1985. It took effect in 1995.

Which countries are part of the agreement?

The first member states were Belgium, France, Germany, Luxembourg and the Netherlands.

Now there are 26 Schengen countries - 22 EU members and four non-EU. Those four are Iceland and Norway (since 2001), Switzerland (since 2008) and Liechtenstein (since 2011).

After the initial five came Italy (1990), Portugal and Spain (1991), Greece (1992), Austria (1995), and Denmark, Finland and Sweden in 1996.

Nine more EU countries joined in 2007, after the EU's eastward enlargement in 2004. They are: the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Lithuania, Latvia, Malta, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia.

Only six of the 28 EU member states are outside the Schengen zone - Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Ireland, Romania and the UK.

The EU explains the evolution of Schengen here, external.

The BBC's Chris Morris explains how the Schengen area was created

Are other countries going to remove border checks too?

Andorra and San Marino are not part of Schengen, but they no longer have checks at their borders.

There is no date yet for Cyprus, which joined the EU in 2004, or for Bulgaria and Romania (joined in 2007) or Croatia (joined in 2013).

Which EU countries are not in Schengen?

The UK and Republic of Ireland have opted out. The UK wants to maintain its own borders, and Dublin prefers to preserve its free movement arrangement with the UK - called the Common Travel Area - rather than join Schengen.

The UK and Ireland began taking part in some aspects of the Schengen agreement, such as the Schengen Information System (SIS), from 2000 and 2002 respectively.

The SIS enables police forces across Europe to share data on law enforcement. It includes data on stolen cars, court proceedings and missing persons.

How have the Paris attacks and the migrant crisis affected Schengen?

Hungary - inside Schengen - was a magnet for migrants hoping to reach Germany

Schengen is often criticised by nationalists and Eurosceptics who say it is an open door for migrants and criminals.

The 13 November Paris attacks, which killed 130 people, prompted an urgent rethink of the Schengen agreement.

There was alarm that killers had so easily slipped into Paris from Belgium, and that some had entered the EU with crowds of migrants via Greece.

In 2015, the influx of more than a million migrants - many of them Syrian refugees - also greatly increased the pressure on politicians, and one after another, EU states re-imposed temporary border controls.

In December, the European Commission proposed a major amendment to Schengen, expected to become law soon. Most non-EU travellers have their details checked against police databases at the EU's external borders. The main change is that the rule will apply to EU citizens as well, who until now had been exempt.

Non-EU nationals who have a Schengen visa generally do not have ID checks once they are travelling inside the zone, but since the Paris atrocity those checks have become more common.

When can countries re-impose border controls?

Belgian and French (yellow vest) police began systematic border checks after the Paris attacks

Under the Schengen rules, external, signatories may reinstate internal border controls for 10 days, if this has to be done immediately for "public policy or national security" reasons.

If the problem continues, the controls can be maintained for "renewable periods" of up to 20 days and for a maximum of two months.

The period is longer in cases where the threat is considered "foreseeable". The controls can be maintained for renewable periods of up to 30 days, and for a maximum of six months.

An extension of two years maximum is allowed under Article 26 of the Schengen Borders Code, external, in "exceptional circumstances".

In the Schengen zone, currently six states have border controls in place, external: Austria, Denmark, France, Germany, Norway and Sweden.

Hungary's controls affect its borders with two non-Schengen states: Croatia and Serbia. Last October it also imposed temporary controls on the border with Schengen member Slovenia.

In 2005 France re-imposed border controls after the bomb attacks by Islamist militants in London. Austria, Portugal and Germany re-imposed border controls for some major sporting events, such as the Fifa World Cup.

What else does Schengen involve?

The main feature is the creation of a single external border, and a single set of rules for policing the border, but there are other measures including:

Common rules on asylum;

Hot pursuit - police have the right to chase suspected criminals across borders;

Common list of countries whose nationals require visas;

The Schengen Information System (SIS), external, which allows police stations and consulates to access a shared database of wanted or undesirable people and stolen objects;

Joint efforts to fight drug-related crime

How are non-EU citizens affected?

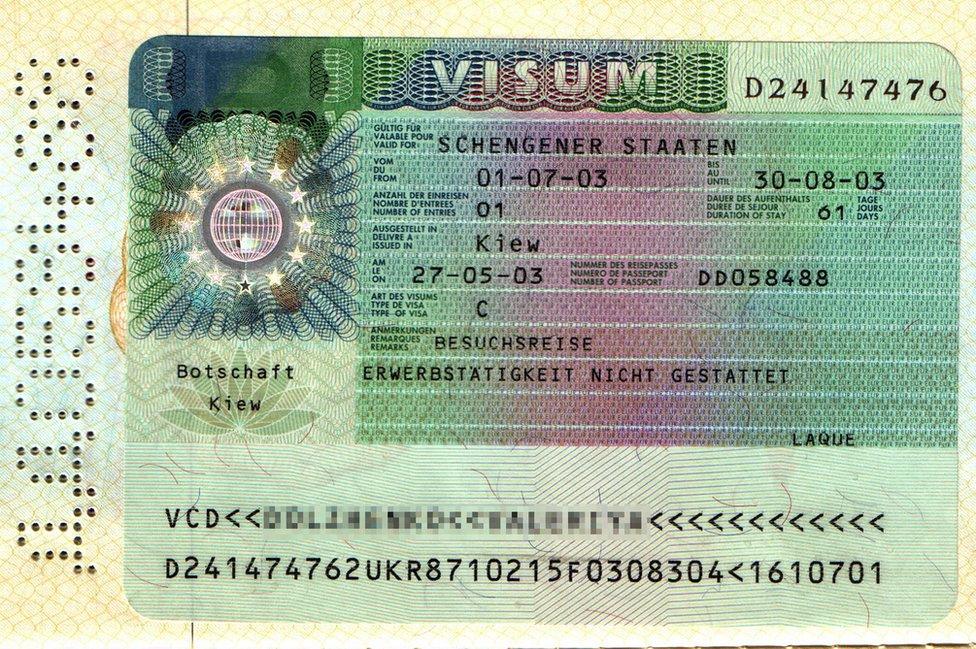

The Schengen visa gives non-EU nationals easy access to most of Europe

Nationals from some countries, external need to obtain a Schengen visa, external in order to enter one of its member countries or travel within the area. It is a short-stay visa valid for 90 days. It also allows international transit at airports in Schengen countries.

A short-stay visa costs €60 (£46; $66), but just €35 for Russians, Ukrainians and citizens of some other countries, under visa facilitation agreements.