German nuclear review throws up new problems

- Published

Chancellor Merkel is pinning her hopes on an expansion of wind power

Germany's dramatic rethink over nuclear power has thrown up new problems, as the consequences of a retreat from atomic technology emerge.

Just after Japan's Fukushima nuclear disaster in March, Chancellor Angela Merkel announced a review of energy policy and ordered Germany's oldest reactors to be shut down immediately, and perhaps permanently.

Only a few months earlier, she had decided to keep the reactors running past their original shutdown dates.

But only now comes the hard bit. Power companies have warned of higher prices because of the shutdown; Germany has imported electricity to meet peaks in demand; analysts have warned that coal-fired power stations will be boosted - and nuclear ones in the nearby Czech Republic and France.

And right in the heart of the country, protest groups are raising their voices as they realise that rejigging a country's energy industry means redirecting the transmission lines through their picturesque backyard.

North-south energy route

The difficulty is that many of the threatened nuclear power stations are in the south, situated conveniently for the big energy users like the cities of Munich and Stuttgart and manufacturers like Volkswagen.

If these southern nuclear generators are decommissioned, the idea is that wind farms in the north might take up the slack. But that implies new high-voltage cables with very high pylons to match.

As Johannes Teyssen, chief executive of the huge energy company E.On put it: "We lack the necessary power lines to transmit wind-generated electricity from the north. This could lead to massive problems in the grid, even power outages."

To avoid that, a new grid of high-voltage cables is proposed, what has been called an "Energie Autobahn" right through the heart of Germany.

Concerned residents of Schalkau fear new pylons will spoil their countryside

The route goes through the Rennsteig, the beautiful ridge of deep-green, forested hills that stretches for more than 160km (100 miles) down the centre of the country. It is where Germans come to hike in what they feel is the idyllic embodiment of their country, a part of the essence of Germany.

So there is much opposition to the energy highway. Different parts of the green movement pull against each other. Activists do not want nuclear power, but nor do they want a landscape disfigured by what they call "mega masts".

Costly green solution

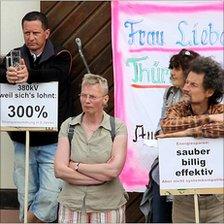

In the town of Schalkau, nestling quietly high in the Rennsteig, the citizens demonstrated recently. They are not naturally a demonstrative people and the protest meeting was suitably sedate. They drank beer and ate sausages at trestle tables as speaker after speaker denounced the pylons that they felt would disfigure the beloved landscape around them.

Some told the BBC they were very anti-nuclear. But they were also very anti the power cables entailed by the expansion of wind power.

I asked them what the alternative was, and got various answers: "use the existing power lines" or "put them underground". The authorities say these proposals would either not do the job or would be much more expensive.

On top of the objection to power lines in the region, there is also concern about animals like the black stork, the red kite and the crane, all of which nest in or migrate through areas likely to have more pylons and high-voltage cables, into which they might fly and be killed.

Germany's Economy Minister Rainer Bruederle said planning rules should be changed so that applications could be handled centrally. That would take decision-making further from the local opponents of particular projects and nearer to a national body, which would take into account national needs.

So Germany - like other countries repelled by nuclear power - now has some tough choices. Wind is not an easy, cheap and swift alternative. Another unpleasant fuel may be easier - but it is one which green activists hate: coal.

Professor Claudia Kemfert, an energy economist at the Institute of Economic Research in Berlin, thinks the Japanese disaster will boost coal all over the world.

"I think CO2 emissions will increase tremendously in the next decades because more and more countries will use more coal like Germany. And that's a sad story [for] climate change," she said.

Through this morass of trade-offs, conflicts and choices, Chancellor Merkel's review is attempting to step carefully.

Its chairman, Rudolf Wieland, said it was reassessing the implications of all kinds of events in a new light, including hijacked planes being crashed into reactors. It was reviewing the effect of events only likely to occur every 10,000 years, rather than under the previous assumption of every 1,000 years.

He recognised that there is much emotion surrounding nuclear power, but said it was important not to let that overrule cool judgement. "From the technical view, we always look at how high is the risk, not the emotional part."

The difficulty is that emotions now run deep - emotion against nuclear power, but also emotion against coal. And emotion against disfiguring the green hills of central Germany with pylons carrying electricity from wind farms.

- Published25 April 2011

- Published12 September 2011

- Published15 March 2011

- Published18 March 2011

- Published28 September 2010