Eurozone countries pressure Greece to step up reform

- Published

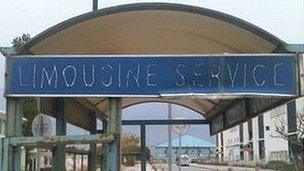

The abandoned terminal building at Greece's old international airport stands as a symbol of decline

"We know we need to change. The era of sweeping uncomfortable truths under the carpet is over."

That admission came from Greek Prime Minister George Papandreou this week, with his country facing what felt like a series of ultimatums from elsewhere in the eurozone.

As Europe's sovereign debt crisis continues to unfold, Greece has been told in no uncertain terms that now is the time for action.

It needs to step up the pace of economic reform, says the cream of Europe's financial elite, and make rapid progress in a privatisation programme designed to raise 50 billion euros ($71bn; £44bn) to help reduce its debt.

Mr Papandreou, speaking at a conference in Athens, said remarkable reform was already happening but Greece was not being given the credit it deserved.

"No-one should doubt our commitment and resolve," he said.

And yet they do.

Grounded economy

In the southern suburbs of Athens, the abandoned terminal building at the city's old international airport stands as a symbol of promises unfulfilled.

Closed down a decade ago, the site includes 170 acres of prime coastal land on the shores of the Aegean sea and for some time there have been ambitious plans to sell it for redevelopment to the Gulf state of Qatar.

But so far they are just that - plans. And that makes the rest of the eurozone jumpy.

"The complaint from the Germans and the Dutch," says Anton La Guardia, who writes on European affairs for The Economist, "is that not a single euro worth of asset has been privatised."

"These days it's the message coming down from just about everyone. The Greeks have to start selling some stuff in order to raise money."

"It can't all come from the rest of the EU. Voters are rebelling."

Easier said than done, say the Greeks.

Greeks are having to get used to a new age of austerity

But this week, in response to the demands from other European capitals, they released a long list of privatisation projects they intended to "expedite" - from state lottery tickets to real estate assets, from motorways to the Public Gas Corporation.

"All right let's sell, but to whom do we sell?" asks the Greek Culture Minister Pavlos Geroulanos, who is trying to find a buyer for many of the buildings constructed for the 2004 Athens Olympics.

He points out that one project put on the market twice recently attracted no bidders at all.

"The global market is kind of nervous right now," he adds. "From America to China to Japan they're being cautious, and they're being overly cautious about Greece."

"We know we have a lot of hard work to do, but we can't make something out of nothing."

And that is a common theme here - that Europe is too impatient, there are no instant solutions, and huge economic change does not happen overnight.

United we stand?

In reality Europe is not expecting 50 billion euros of sales. Realistically, 20 billion would be a good start. But one practical problem with privatisation is working out whether the state actually owns the land it thinks it does.

"Greece's land registry is not the most perfect record-keeping system on the planet," says Richard Parker, an American political economist who is a long-standing friend and adviser of the Greek prime minister.

"It takes time to put everything in order. And so I think it's pretty harsh of Brussels to be pushing them to do something which if they do it quickly can end disastrously."

"From a European point of view, would you rather Greece had more money in its pocket to repay the loans or less? It's that sort of question."

And while there is no doubt the government in Athens is feeling the pressure from the rest of Europe, it also has to balance that against the pressure rising from within.

Striking Greek teachers march against cost-cutting reforms

Austerity is hurting, and to some extent the judgment of sustaining any programme of economic reform has to be political - how much can people take?

Costas lost his job in sales six months ago, and his wife is seven months pregnant.

"It's terrible to feel useless," he says, as we sit in a city centre cafe.

"More and more I hear about people I know who lose their jobs or work extra hours without getting paid."

"It was a difficult situation already, but now it's going to be a jungle."

And that is one more reason why Greece still hopes for solidarity when it looks to the rest of the eurozone. Solidarity means more financial assistance, a second bail out to give it more time to recover.

Even that may not be enough, and it is becoming an increasingly tough sell across the continent.

But the Greeks seem to think they have an ace up their sleeve. If you want to stick with the euro, they argue, you need to stick with us.

The alternative could be much worse, and even more expensive.

- Published13 May 2011

- Published20 May 2011