Q&A: EU response to Iceland volcano ash

- Published

Germany was worst hit by disruption on Wednesday

The eruption of Iceland's Grimsvotn volcano has spread fears that Europe could see a repeat of last year's ash cloud chaos, in which millions of air passengers were stranded.

But the EU and aviation officials say that this eruption is much less threatening, partly because of the ash itself, but also because of the weather and the measures taken by the EU since the last Icelandic eruption.

Is Europe better prepared this time?

In April 2010 the ash cloud from Iceland's Eyjafjallajokull volcano triggered the biggest aviation shutdown in Europe since World War II. It was an enormously costly "one-size-fits-all" approach that put passenger safety first, but without measuring the different degrees of risk.

This time the EU has activated a new crisis cell, bringing together experts from the European Commission, the European air traffic controllers (Eurocontrol), the aviation industry and airports. The European Aviation Crisis Co-ordination Cell (EACCC) is responsible for co-ordinating the response to this and any other air traffic crisis affecting Europe.

As before, it is up to each EU member state to decide whether or not to restrict flights in its airspace. But the aviation authorities are using new guidelines which specify three degrees of ash contamination.

The blanket flight ban last time infuriated the airlines, so this time the airlines themselves are largely deciding whether or not to continue flying, based on their own assessment of the airborne contamination.

The hope is that the new approach will greatly reduce the number of flights that have to be cancelled.

About 500 flights were cancelled in northwestern Europe on Tuesday, with Scotland, Northern Ireland and northern England especially badly hit. On Wednesday it was Germany suffering the worst disruption. But airports are getting back to normal now.

In April the EU carried out a large-scale exercise to test the EACCC's response to another ash crisis. It was based on an eruption of Grimsvotn - just weeks before it happened for real.

Who is advising the airlines and governments about the ash?

The UK Meteorological Office and its Volcanic Ash Advisory Centre (VAAC) are providing data on the progress of the cloud.

So far the UK has been worst hit, but disruption has now spread to Germany, where Bremen and Hamburg airports closed early on Wednesday.

The airspace over Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg and northwestern Germany is now being monitored by a Dutch control centre in Maastricht, called MUAC.

Berlin's airports are due to shut down later, but VAAC says the cloud is likely to dissipate as the volcano's eruption subsides.

What problems remain for Europe's aviation in such crises?

The European Commission says it is proving very hard to establish a safety threshold for volcanic ash. In each eruption the composition of the ash differs, and the weather also affects the degree of risk.

Later this year the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) will issue proposals calling for engine manufacturers to provide detailed data on the risk posed by different types of volcanic ash. That will be a big help to airlines when assessing the flight risk during an eruption, the Commission says.

Iceland and the VAAC now have more advanced equipment to measure volcanic ash and model its likely distribution and concentration.

The EU is still a patchwork of 27 different national air traffic zones, each able to impose flying bans.

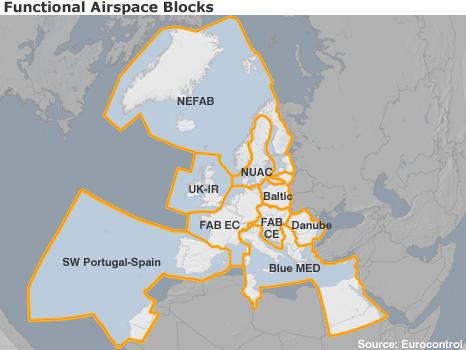

But the Commission is now developing a new integrated structure for air traffic management. Nine Functional Airspace Blocks (FABs) will replace the existing 27 areas. This is part of the revised blueprint called Single European Sky II (SES II), external.

The deadline for all nine FABs to be up and running is 4 December 2012. Three are already operational, including the UK/Ireland FAB.

Under the EU plan, an air traffic network manager will co-ordinate Europe's air traffic resources daily - but without taking over from the national air traffic controllers.

The network manager will deal with route design, traffic flows and technical tasks, such as allocating transponder codes and aeronautical frequencies, which are done for every flight.

The aim is to avoid the communication delays and confusion over data seen in the 2010 ash crisis.

- Published24 May 2011

- Published24 May 2011

- Published23 May 2011