Turkey election: Erdogan's economic trump card

- Published

Recep Tayyip Erdogan's face has dominated the election campaign

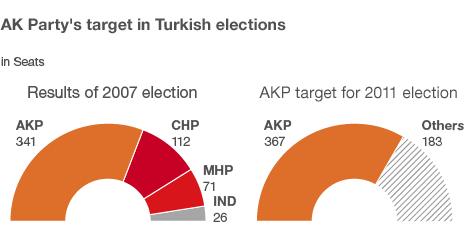

If, as expected, Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan wins a third term in Sunday's general election, he will become the most successful democratic leader in Turkey's history. So what explains his extraordinary dominance of Turkish politics?

On an international stage, the prime minister often cuts an awkward, slightly defensive figure, tall, but stiff and unsmiling. On his home turf, though, he comes alive, responding with jokes, sarcasm and even poetry to the crowds of supporters who pack his rallies.

He has the combative charisma that Turks of the teeming cities or small Anatolian towns love. He is a towering politician who has come to dominate his country at a time of transition, in much the same way that Margaret Thatcher, Helmut Kohl and Mikhail Gorbachev did theirs.

But it has been a tough and sometimes bad-tempered campaign.

For all his popularity, Mr Erdogan is a polarising figure who, in his second term, has lost the support of many Turkish liberals and intellectuals who once saw him as a democratic pioneer, pushing back the militaristic state that ruled the country for most of the 20th Century.

'Growing intolerance'

"I never deluded myself that they are super-democrats," says journalist Nuray Mert of Mr Erdogan's party, the AKP.

"I was supportive of their move for a more democratic and civil Turkey, but it didn't work here because Erdogan got overwhelming power, and he never considers compromising or consulting with others."

Nuray Mert has recently been on the receiving end of some particularly harsh personal attacks by Mr Erdogan for an article she wrote. He takes criticism badly, and often sues journalists or artists who portray him in an unfavourable way.

It is even worse for the 57 Turkish journalists who are in prison, the highest number of any country.

Many have been charged with involvement in a complex and murky conspiracy , known as Ergenekon, which the government says was nothing less than a military plot to overthrow democracy. Hundreds of army officers and civilians have been jailed, sometimes for years. So far, none has been convicted.

"In the first term, they were more receptive to protests and recommendations from NGOs - there was progress," says veteran human rights campaigner Ozlem Dalkiran.

"But in their second term, they were less tolerant of opposition, and police violence against demonstrators increased enormously. They changed the anti-terrorism law so that demonstrators are tried as if they are members of a terrorist organisation."

The charge of increased brutality by the police is one it is difficult for the government to duck, because while it has had an often confrontational relationship with the military and judiciary, the AKP is believed to wield strong influence over the police.

AKP politicians insist that no journalists have been detained purely for what they have written.

But these concerns will not affect the core support for Mr Erdogan, which is substantial.

Economic trump card

"They are well-structured within Turkish society," says journalist Cengiz Candar.

"Turks are a pious, religious people, so the AKP has strong grass-roots power. They are not Islamists, they are Muslims, religious people, but the party is not an Islamist party. So they claim to replace those right-wing or centre parties which were thrown into turmoil by successive military coups."

Mr Erdogan's greatest achievement has been to stabilise the Turkish economy. Up to a decade ago, the country lurched from one crisis to another, with sky-high inflation and interest rates and a feeble currency.

Booming economy: Ford Transit vans are now almost entirely manufactured in Turkey

Today Turkey is the envy of the region, enjoying economic growth rates close to China's, its companies competing successfully in the EU, the Middle East and increasingly further afield, in Africa and Central Asia.

Bulent Aymen is not a natural AKP supporter. He is the managing director of a group of companies specialising in forestry products but he is not one of the pious, provincial entrepreneurs that make up the bedrock of its support. He would welcome another AKP term of office.

"In 2002, per capita income was $3,500 (£2,100) - in 2010 it's $10,000," he says.

"Total exports were $30bn in 2002; this year we are going to make $134bn."

He talked about the impact on his business of the glowing image Turkey now enjoys in the region, thanks to its assertive new foreign policy.

"We went to Qatar and Kuwait with the prime minister in January and you cannot believe the reaction we got - he is a hero to them.

"It has a positive effect on our business: we can do business there much more easily now than other countries."

Mr Erdogan is campaigning on a theme of "You've never had it so good", with a promise of more to come.

Every poster mentions what he calls his "crazy schemes" - a plan to drive a canal from the Black Sea to the Marmara Sea, a new city to be built outside Istanbul, a third airport, a third bridge over the Bosphorus, new hospitals, new housing.

For millions of Turks living close to poverty, this is an irresistible message, although it certainly worries environmentalists. The prime minister once told me his proudest boast was turning all 81 provinces into building sites.

On his posters, the giant figure of Recep Tayyip Erdogan looks firmly towards the future, with the year 2023 in large letters beside it. That is when this country will celebrate its centenary, and Mr Erdogan implies he will still be running the show. At the age of just 57, few people here would discount that possibility.

- Published10 June 2011

- Published9 June 2011

- Published4 June 2011