Norway and the politics of hate

- Published

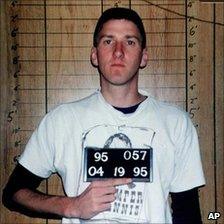

Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh saw the government as his enemy

Back in 1985, I was in the US reporting on the emergence of right-wing militias. They were springing up across the Midwest. Some were little more than gun clubs. Others trained men in uniform.

They believed that their idea of America was under threat. Many saw the federal government in Washington as the enemy, staffed with officials who were betraying America's core values.

A strong strain of paranoia ran through their conversation and publications. I recall a man showing me a grainy photograph, claiming it proved there were secret Russian bases in Michigan.

Most of this reflected the margins of a society and could easily be dismissed. But the idea that his government was the real enemy worked away inside the mind of a young man called Timothy McVeigh. Sometime later he packed a van with fertiliser and diesel fuel and blew up the federal building in Oklahoma, killing 168 people.

I was reminded of America's paranoid strain as I read through the manifesto of Anders Behring Breivik who admits carrying out the bombings and shootings in Norway.

For at least nine years he carried anger towards the changes occurring in Norwegian society. He did not accept the multicultural country that was emerging. It threatened his identity and he felt alienated from it. He was in contact with other extreme groups who increasingly saw Islam as a danger and the enemy.

Chilling words

For the past three years Breivik was writing his manifesto, counting down to the moment when he would use terrible violence against his own state and people. Two months ago he went out and bought six tonnes of fertiliser.

Like McVeigh, he would come to see his country's political establishment - which in his case had run Norway since World War II - as the real enemy.

"What most people still do not understand is that the ongoing Islamicisation of Europe cannot be stopped before one gets to grip with the political doctrine which makes it possible," he wrote.

So the target that formed in his mind was not immigrant groups, but the government itself, and young people who were attached to the ruling left-leaning Labour Party.

His lawyer said that "he had been politically active and found out himself that he did not succeed with usual political tools and so resorted to violence".

In his own chilling words, the killings were "atrocious but necessary".

Survivors I have spoken to speak of his calmness: a man locked in an internal world of hatred but maintained by a belief that what he was doing was justified.

From his own tweets, paraphrasing the English philosopher John Stuart Mill, you can glimpse his twisted certainty: "One person with a belief is equal to the force of 100,000 who have only interests."

'Nazi movie'

Again his lawyer said that "he wanted a change in society, and from his perspective, he needed to force through a revolution. He wished to attack society and the structure of society."

Judging from the pictures of him dressed in a variety of uniforms and carrying automatic weapons, he had developed a strong fantasy as to who he was. One survivor told me he felt he was watching a Nazi movie.

Across Europe there is a strong and growing concern about immigration. It is partly fuelled by unemployment but also has its roots in threatened identity.

Societies have been changing fast. There is mounting frustration that officials at both European and national level seem not to listen to the views of the voters.

With globalisation, national identity seems to have become more important. The nation state stubbornly remains the focus of most people's identity. And so nationalist parties have made gains in many parts of Europe.

There are frequent expressions of concern about the growing influence of these parties. Others say that they provide a useful channel for the feelings of frustration and alienation.

Some of Europe's leaders, from Angela Merkel to David Cameron, have questioned multiculturalism.

The danger, of course, is that such statements can encourage extremism. Others say that in Europe the debate needs to be had, openly and transparently about immigration and multiculturalism.

It cannot be hidden away because it feeds a paranoia but it is one of the most sensitive issues in Europe today and is rising up the agenda.

It is difficult to estimate the extent of extremism. Governments across Europe will be re-directing their intelligence agencies to give an assessment.

Norway's tragedy will be used by some to speak of the dangers of populism. Others will insist that openly and sensitively these questions must be examined and not left to the internet chat rooms.

It is not clear, of course, whether anything could have dissuaded Breivik. It is too early to judge. He has admitted the killings but not accepted criminal responsibility.

The prime minister of Norway has said "you will not destroy democracy".

Overwhelmingly, there is a total revulsion at these crimes. The nation is heartbroken at the young faces staring out from the front of papers and who are still missing. The hatred that did this is incomprehensible to most people.

But these terrible events will prompt a time of reflection in Europe.