Winners and losers in the new Baku

- Published

As I turn the corner into Shamsi Baidabeili Street in central Baku I suddenly feel completely disorientated.

One side of this pleasant low-rise, 19th-Century street has been demolished. Many of the houses on the remaining side are no more than empty shells waiting to be knocked down.

It is all part of a plan to redevelop the area.

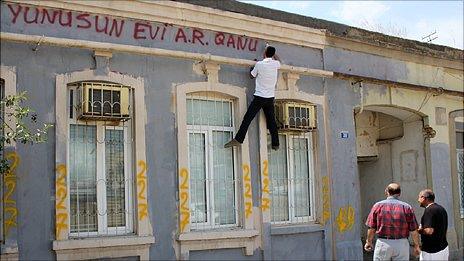

On the day I visit, a local human rights organisation that is based on the street is organising a protest.

A young man shins up a drainpipe and starts spray-painting slogans on the wall of the house defending its owners' right - under Azeri and European law - to occupy the building.

It is not the first time he has done this. And each time someone has come round after office hours and quietly painted over the slogans with grey paint.

Eviction process

Local residents gather to support the protest. Everyone has a story to tell. They are all angry and stunned - not just to be losing their homes. But also at the way in which they say the authorities have managed the whole compulsory purchase and eviction process.

"We were given two weeks to pack our things and leave," one woman tells us. "When we said 'no' the police came to the house at night. They shouted at us.

"They called my daughters prostitutes. I've worked honestly for this country all my life. What have we done to deserve this?"

Former residents have tried to salvage scrap metal from the ruins on Shamsi Baidabeili Street

People show us mobile phone recordings of police heavies smashing down doors, and of excavators moving in as shocked residents stand by and watch.

They take us further up the road to see a building that was knocked down earlier that day. The gas pipe that was fixed onto the side of the house is now propped up with a bit of wood. It hasn't been sealed off and there's a smell of gas in the air.

Two doors down is a derelict building. Shockingly there are still two families living in the rubble filled rooms. One is a mother with three little girls. The other is a refugee from Azerbaijan's devastating war with Armenia during the 1990s.

"Where will you go?" I ask her. "I don't know, she says flatly. Where would you go if you were me?"

This is the dark side of a massive, oil-fuelled urban development programme which is rapidly turning the Azeri capital into a Caspian Sea version of Dubai.

And it is all the more sad because this is a programme which does have many positives.

City of light

When I first came to Baku in 1995 the city was still in shock from more than half a decade of war and civil unrest.

There were frequent power cuts. The once-lovely 19th Century buildings on the sea front were dark and crumbling.

Now it is a city full of light and life. Mansions built by oil barons from the past have been restored to their former glory.

Grim Soviet-era public buildings and tower blocks have been transformed with a new facade of trademark honeyed sandstone.

The sea-front boulevard has been repaved and landscaped and is full of flowers and lawns. There is even a shiny new shopping centre complete with glass lifts, a food hall and a multiplex cinema.

Yes, some of the new mirror-glass sky scrapers are completely over the top and look out of place in what was always a cosy kind of city.

And the breathtakingly conspicuous wealth being flaunted by the privileged few who can afford to frequent the downtown designer boutiques is quite shocking to see.

But for the ordinary families enjoying a stroll in the sunshine, or going shopping in the new Debenhams department store, Baku's makeover has made life much nicer in many ways.

But the people on Shamsi Baidabeyli Street do not feel part of any of this. The heart is being ripped out of their neighbourhood and they are not being offered much in return.

A once-cosy city is being rapidly transformed by oil money

And there is little prospect of taking on the system and winning.

Leyla Yunus, the head of the human rights organisation on Shamsi Baidebeyli Street, says she has written eight letters to the interior ministry outlining specific complaints about police behaviour over the evictions. She has not received a reply to any of them.

Her attempts to pursue her case through the courts is also running out of steam with a succession of judges refusing the take on the case and referring it onto someone else.

She now has her sights set on the European Court of Human Rights.

City officials are quick to play down criticism of the demolitions.

"When you try to do something good there will always be some negative reaction," Hadi Recebli, an MP from the ruling YAP party who heads the Azerbaijani parliamentary committee on social policy issues, told the BBC.

He said all demolitions in Baku were being carried out with the sanction of the court. And he dismissed resident's complaints that they weren't being offered a fair rate of compensation for their homes.

"Some people give in to their emotions when they tell you things like this" he said. "I think some of the cases you are mentioning didn't really happen and couldn't happen."

The Baku mayor's office did not offer to speak to the BBC.

Back on Shamsi Bediebeyli Street the protests and the evictions are continuing and the overwhelming emotion of local residents seems to be anger.

They feel humiliated to be treated as an inconvenience by city officials who seem prepared to bulldoze both the homes and rights of its poorest people in the pursuit of their dream for a new city.

And that new city seems all the poorer for being built on the ruins of the lives of some of its most vulnerable inhabitants.

Additional reporting by Konul Khalilova

- Published22 July 2011

- Published18 May 2011

- Published24 April 2011

- Published1 March 2011

- Published2 June 2010